By Ed Staskus

Frank Gwozdz kept his eyes fixed on the middle of nothing. He wasn’t minding his own business even though it looked that way. He wasn’t tall or short. He wasn’t thin or chunky, either, except when he wore a bulletproof vest, which made him look chunky. He was able-bodied enough, although he was near-sighted. The closer something was to him the better he saw it. When he had to, he wore glasses to see far away. He read the Cleveland Plain Dealer every morning except Sundays when there was too much of it. There was hardly anything about him likely to draw anybody’s attention, even though he kept his hair not-too-neat and didn’t shave too often. When he was in a bar, at the bar with a beer in front of him, a Lucky Strike smoking itself at his elbow, nobody gave him a second glance.

He was a Cleveland Police Department detective. He worked out of the third floor of Cleveland’s Central Station at E. 21 St. and Payne Ave. The Central Station had been in business for fifty years. It had replaced the Champlain Street Headquarters long ago. When it did the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported, “The minute the new station opens, the ancient Champlain Avenue mausoleum of crime and rats which has been functioning as a police headquarters for perhaps twenty-five years too long will start to crumble before the wrecking engines.” Fifty years later the Central Station was in the same boat, overflowing with crime and rats.

Frank looked at the bottle of beer in front of him. He took a short pull. It was getting lukewarm. It didn’t matter to him. It was only there so he could sit beside it. He loosened his already loose tie and the top button of his shirt. Mitzi Jerman was working the bar. She asked if he wanted fresh peanuts. “Thanks, but no,” he said. He hadn’t touched the bowl at his elbow. It was still full of old peanuts. The bar didn’t serve food, just peanuts, pretzels, and pickled eggs. He hadn’t touched anything, yet, although he might if the two men he was watching stayed long enough. He was getting hungry. He knew the man with jug ears doing all the talking had worked the numbers game for Shondor Birns before his boss was blown up. He thought the other one had probably been up to the same thing. He wondered why they were near downtown and not the near east side where the Negroes lived. That’s where their bread and butter was at this time of night.

Jerman’s Café was on E. 39 St. and St. Clair Ave., although it wasn’t actually on any street. It wasn’t a storefront like most corner bars, and it wasn’t on a corner, either. It was on the ground floor of a house. It was set back from St. Clair Ave. with a parking lot on the side. If a drinker didn’t know the bar was there he might end up high and dry. It opened in 1908 when a Slovenian immigrant and his wife opened it. It had lived through World War One, the New Deal, World War Two, and the 1956 Cleveland Indians World Series win when the celebrating didn’t stop for days. It stayed open as a speakeasy during Prohibition, not missing a beat. Mitzi’s uncle smuggled booze from Canada during those years, making the run across Lake Erie in a speedboat by himself. Mitzi’s mother and father hid the rum and whiskey with neighbors whenever Elliot Ness was on the rampage.

After cleaning a table with a wet rag Mitzi came back to where Frank was sitting and parked herself in front of him. “Working tonight, young and handsome?” she asked, drying freshly washed glasses with a bar towel. Frank wasn’t exactly young anymore, just like he wasn’t exactly handsome anymore. He took her sweet talk in stride.

“I’m working right now,” Frank said in a quiet voice.

Mitzi had been born upstairs in the apartment above the bar. It was where her parents lived all their working lives. She slept in the room she had been born in. There was a piano and a juke box in the bar. A pool table was at the rear, ignored and lonely. Mitzi watched baseball games in living color on a TV set placed high up on a wall. She was a born and bred Tribe fan. Her dog Rosco slept at her feet. The bar Frank was sitting at was oak. The ceiling above him was zinc. Mitzi served Pabst, Stroh’s, and Budweiser on tap. Everything else came in a bottle. Frank fiddled with his bottle of Anchor Liberty Ale.

One of the men at the back table snapped his fingers. Mitzi threw them a look. They were looking at Betty, the neighborhood girl who worked nights for Mitzi. She was an eye-catcher. Many men wanted to hang their hats on her. Mitzi sent Betty to their table. They ordered two more glasses of Pabst and gave her a pat on the behind for her trouble.

“Are you working those two bums?” Mitzi asked.

“I only work bums, and it looks like they are the only two of their kind in this place right now.”

“Is anything going to happen in my place tonight?”

“Not if I can help it,” he reassured her.

“Are they the Jew’s men?”

“Yeah, Shondor ran them, at least until lately. They’re not pulling any Dutch act about what happened to him. Those two are on the go.”

Shondor Birns had run the numbers game for years, until he was blown up a few months earlier on Easter Saturday outside of his favorite strip club. “SHONDOR BIRNS IS BOMB VICTIM” the Cleveland Plain Dealer headline trumpeted the news. The strip club was Christie’s Lounge, where Shondor Birns spent the evening drinking and ogling naked girls bumping and grinding. When he was good and drunk, he staggered out to his Lincoln Continental parked in a lot across from St. Malachi’s Catholic Church. As soon as he turned the key in the ignition a package of dynamite wired to the ignition came to life. He was blown in half, his upper body catapulted through the roof of his car. Some of him landed in the parking lot. Some of him was sling shotted into the webbing of the surrounding chain link fence. The rest of him disappeared. Celebrants at the Easter Vigil rushed out of the church when the explosion rattled the stained-glass windows.

The numbers man had been arrested more than fifty times since 1925 but was hardly ever convicted. He had killed several men, but no charges ever stuck. He ran a theft ring. He ran the vice game. He became Cleveland’s “Public Enemy No. 1.” When he got into the protection racket many small businessmen discovered they needed protection.

“He was a muscleman whose specialty was controlling numbers gambling on the east side, keeping the peace among rival operators, and getting a cut from each of them,” was how the Cleveland Press, the city’s afternoon newspaper, put it. “He was a feared man because of his violent reaction to any adversary.”

Shondor Birns was always blowing up about something. After he was blown up what little was left of him was buried in Hillcrest Cemetery on April Fool’s Day. When the last shovelful of dirt topped him off he was officially gone. Nobody promised to keep his grave clean. Everybody forgot about him. His mug shot was taken down from the top row of the big board at the Central Station. Somebody else was going to take his place, although the new man’s picture wasn’t on the board, yet. The squeeze wasn’t going to stop with Shondor Birns gone. The next boss was already taking care of business. Frank would find out who that was soon enough.

When the two men at the back table got up and left, Frank got up and left, too. They got into a red Plymouth Duster. He wasn’t going to have any trouble following it. He got into his Ford Crown Victoria. The dark blue car wasn’t much to look at, since it looked like every other unmarked police car in the country, but no other car was going to outrun it if it came to a chase. The Duster drove to E. 55 St. and turned on Euclid Ave, When it got to Mayfield Rd. it turned again going up the hill to Little Italy. They parked behind Guarino’s Restaurant and went in the back door. Frank parked five spaces away, near the entrance to the lot.

He turned the car off. He was hungry but didn’t go inside right away. He thought about going home. Nobody had assigned him this shadow job. He had taken it upon himself. He could go home anytime he wanted to but he didn’t want to go home. He wanted to see his boy but didn’t want to see his wife. Sandra had been getting unhappier by the day since the day she had stopped nursing their son. That was three years ago. She was miserable at home and had taken to drinking. Frank threw away every bottle he found hidden somewhere, but he never found the last bottle. He could smell it on her breath every day when he got home.

She was eleven years younger than Frank. He knew marrying her was a mistake but at the time he hadn’t been able to control himself. She had become spiteful and patronizing. She complained about him being a policeman. She complained about his unpredictable hours. She complained about his pay and how he dressed. When he tried to explain the dress code behind being a plainclothes man, she was snotty about it, calling him “you poor dear man.”

They didn’t kiss anymore, much less talk. She complained about the housework, even though she did less and less of it. She had started to neglect their child, leaving the boy with a teenaged babysitter those afternoons when she went to the Hippodrome Theater.

“What’s at the Hippodrome?” he asked.

“The movies,” she said.

“What’s showing today?”

“I’ll find out when I get there.”

The Hippodrome had the second largest stage in the world when it was built in 1907. It was in an eleven-story office building with theater marquees and entrances on both Prospect Ave. and Euclid Ave. in the heart of downtown. It hosted plays, operas, and vaudeville, at least until the movies took over. After that it was all movies. It became the country’s biggest theater showing exclusively big screen fare. A new air conditioning system pumped in cold water from Lake Erie, keeping everybody cool on sweltering summer nights.

Frank followed her there one day on the sly. She went to the Hippodrome but didn’t go to the movies. She went downstairs to the lower-level pool hall. She walked to the back and through a door marked “Private.”

“What’s behind that door?” Frank asked one of the pool players.

“The boss is behind that door,” the pool player said.

“Would that be Danny Vegh?”

“Naw, this is Danny’s joint, but Vince runs the place,” the man said. “Why all the questions?”

“No reason, just curious.”

“If you want to see Vince, you don’t want to right now. He’s got a woman in there and it’s going to be some time before they finish up their business.”

“Thanks pal,” Frank said. “How about a game of nine ball?”

An hour later and fifteen dollars the worse for wear, Frank gave up. His wife was still in Vince’s office. The door was still shut tight. He walked out and up the stairs to Euclid Ave. He crossed the street, leaned against a light pole, and lit a Lucky Strike. Sandra walked into broad daylight a half hour later. A car pulled up to the curb and she got into the front seat. Frank followed the car to their home in North Collinwood. The car pulled into the driveway. His wife got out and went in the front door. The car drove away.

“Son of a bitch,” Frank muttered. It was looking like she was a wife and mother gone wrong, gone over to monkey business. She had promised him at the altar far more than he was getting. He wasn’t getting any of her love. There was no mistake about that. He could kill her for what she was doing, except for the boy. Stanley deserved better than a whore for a mother. He might kill her for that reason alone. There was more than enough room in the backyard for an unmarked grave. He could plant poison ivy to memorialize the spot.

Frank’s stomach grumbled. He was dog hungry at the end of a long day. He hadn’t popped even one peanut into his mouth at Jerman’s Café. He could eat at the trattoria and keep an eye on the two collectors at the same time. He got out of the Crown Victoria, locked it, and walking across the brick patio went into Guarino’s. The restaurant had been around since before the 1920s. A Sicilian family ran it then and the same Sicilian family ran it now. It had been redecorated in a Victorian style in 1963, but the décor didn’t affect the food. Mama Guarino led him to a two-top table. He ordered veal saltimbocca. The waitress brought him half a carafe of chianti. He took his time eating, making sure his wife would be asleep when he got home.

He had always thought there was nothing more romantic than Italian food. He wasn’t feeling romantic tonight, but leastways the food was good. He took a bite of veal and gulped down a forkful of angel hair. No man could love a cheater and not pay the price for it. Things fall apart when they’re held together by lies. His thoughts grew dark. He filled his wine glass with relief and drank it slowly. His thoughts were dark as the bottom of an elevator shaft.

Excerpted from the crime novel “Bomb City.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Bomb City” by Ed Staskus

“A police procedural when the Rust Belt was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

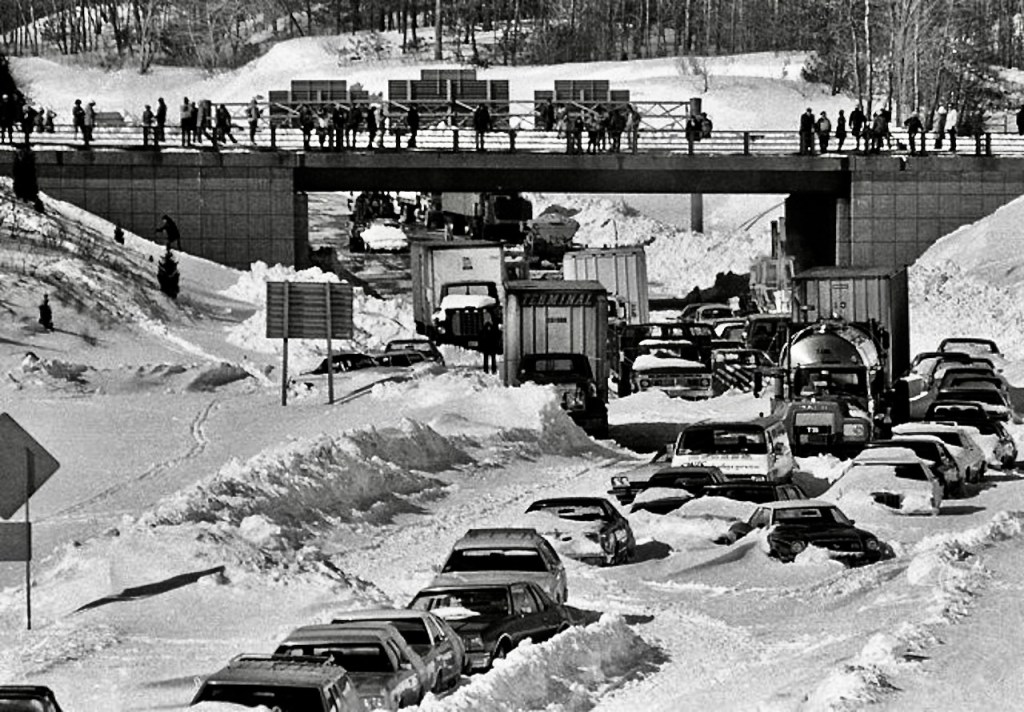

Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. It gets personal.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication