By Ed Staskus

I was in my mid-teens when I started nodding off at Sunday mass. Before long I was snoozing at the drop of a hat, no matter what time I had gotten to bed the night before. My mother was a go-along Catholic but my father was a true believer, so the whole family went to church weekly. Part of my problem was familiarity. I had been an altar boy and knew the ceremony inside and out. I even knew the Latin, what was left of it, not that I knew what any of it meant. The other part of my problem was my growing belief in deism. I didn’t disbelieve the Roman Catholic theology but I didn’t believe it, either. I thought the Golden Rule and the Ten Commandments were good ideas, but that was as far as my commitment went.

The Sunday in 2005 I first saw Jane Scott she was in a back pew at the First Church of Christ in Rocky River, Ohio, one suburb west of where my wife and I lived in Lakewood. I wasn’t a member of the congregation but my wife was. I went to services with her sometimes. Jane was wearing red glasses and a wide-brimmed church crown. She was out cold. I recognized a kindred spirit when I saw one.

When the service was over my wife made her rounds, saying hello and goodbye, chatting with the churchgoers she knew best. I stayed to the side. By the time we were ready to go Jane Scott had shaken off the sandman. My wife talked to her for a minute before we left for home.

“That lady you were talking to, the one with the red glasses, she looked familiar, even though I don’t think I’ve ever met her before,” I said.

“That’s Jane Scott,” she said. “She used to write for the newspaper. She was their rock ‘n roll reporter until she retired a couple of years ago.” She was in her early 80s the day she retired. She had long been known as “The World’s Oldest Rock Critic.”

She went to work for the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1952, three days after Alan Freed hosted the Moondog Coronation Ball, the world’s first rock ‘n roll concert. She covered the local social whirl through most of the 1950s. Starting in 1958 she wrote the “Boy and Girl” column. It targeted seven-and eight year-olds. She wrote “Senior Class” about issues relevant to senior citizens. “I covered everything from pimples to pensions,” she said.

She reviewed the Beatles concert when they first appeared in Cleveland in 1964 and two years later interviewed them before their sold-out rock fest at the 80,000 seat Municipal Stadium. “I never before saw thousands of 14-year-old girls, all screaming and yelling. I realized this was a phenomenon. The whole world changed.” She was going on nearly fifty years of age when her interview with the Fab Four appeared in the newspaper.

When she became the rock critic for the Plain Dealer the newspaper became the first major newspaper to have a full-time music critic on staff. “Once I found rock I was never interested in anything else.” Not everybody considered rock ‘n roll to be music. Many considered it to be noise for the neck down. “This rock and roll stuff will never last,” said Mitch Miller, a maestro of the singalong. Others thought it was the “Devil’s Music.” They didn’t like hips gyrating and lyrics on the other side of pious.

Jane Scott was a Christian Scientist as well as a boogie on down correspondent. I don’t think she gave a damn about Satan. She knew full well he wasn’t interested in music of any kind unless it was the funeral march kind. He marched to the beat of doom and death. She was a live wire.

“My husband Harry was Jane’s first boss when she started at the Cleveland Plain Dealer,” said Doris Linge. “Since she and Harry worked together, I would often get invited to her wonderful annual holiday party. She was a character, quirky and real.”

Jane Scott was born in Cleveland less than a year after the end of World War One. She graduated from Lakewood High School and later from the University of Michigan. She tried out for the college newspaper but didn’t make the grade. During World War Two she enlisted in the Navy, rose to lieutenant, and worked as a code breaker. After the war, back home, she got a job as Women’s Editor for the suburban Chagrin Valley Herald, a community rag.

She went to Sunday services. She taught Sunday School. “Jane was a member of the Fifth Church, which was on the border of Lakewood and Cleveland,” said Doris Carlson, a member of First Church in Rocky River since 1957. “When it closed she came to our church. I remember seeing her on the TV news once in 1962, when she performed at an honorary birthday party here in town for President Kennedy. She was a hoot. She sang ‘Happy Birthday’ the same way Marylin Monroe did, even though she was practically a middle-aged woman. She could be sexy when she wanted to be.”

The 1960s came and went and she missed her chance to go to the Woodstock Festival. Twenty five years later she went to the 25th anniversary show at the age of seventy five, tramping through the same kind of mud on the same kind of wet weekend. “I am going to try to make the 50th anniversary in 2019,” she said. If she made it she would be one hundred years old, she was reminded.

“I don’t like the word retirement,” she said “Rock ‘n roll is excitement. It’s that unity of feeling you get when the audience is loving and sharing the music together. It’s the unexpectedness and the swift changes. You go from pop to hip-hop. It all melds into rock somehow. It keeps you on your toes.”

Covering shows night after night, being on the short side, she always tried to get up front so she wouldn’t have to stand on her toes to see over fans. She always carried the same hefty bag slung over her shoulder. “I call it my security kit,” she said. “It includes ear plugs, Kleenex, because when you are at a show with 80,000 people they are sure to run out of toilet paper, safety pins to pin my car keys and backstage pass on, at least four pens because people borrow them and don’t return them, and two notebooks, one for interviews and one for observations.” She always had a peanut butter sandwich in the bag. “Peanut butter doesn’t spoil and sometimes you don’t have time to stand in line for food.”

When it came to rock ‘n roll, she always had ants in her pants for the next show and the will power to see her chronicles of the new music through. “She was allowed to take the rock beat because the newspaper thought it was trivial at the time, and a woman could have it,” said Anastasia Pantsios, a Plain Dealer writer and photographer. She had good energy, keeping at it for nearly forty years. “She literally did it ‘my way,’ independent, not afraid to go places by herself, with so much tenacity and work ethic,” her friend Mary Cipriani said.

Jane made it a point to interview music makers with opinions, contentious musicians like Lou Reed and Frank Zappa. Lou Reed and she were close friends from the late 1960s until their deaths two years apart. “She was one of the only ones to treat me with respect in the early years,” Lou said. “Always fair, always interested.” The man who became the Grandfather of Punk called her Sweet Jane after his song of the same name.

The first time Jane saw the Velvet Underground hardly anybody in town noticed they were in town. There might have been as many people in the audience as there were in the band. The band was Lou Reed, a bad-tempered young man from Long Island, Sterling Morrison on guitar, the violist John Cale who doubled on bass, drummer Moe Tucker, who did her drumming standing up, and the partially deaf actress Nico, who sang in deadpan English with a German accent.

“I don’t know just what it’s all about but put your red pajamas on and find out,” Lou Reed said.

Jane Scott was smitten the minute she heard the sound the band made. The man she had been waiting for sounded somewhere between Bob Dylan and Sonic Youth with some Andy Warhol thrown in. The band was about Beat poetry, Pop Art, and the French New Wave. Jane was good with the offbeat but kept the beat steady in her head.

The Velvet Underground lasted until the early 1970s. When Sterling Morrison left the band he put his guitar down for a foghorn. He found work as captain of a tugboat and later earned a PhD in Medieval Literature. Moe Tucker formed her own one-gal band playing proto punk. The old Lou Reed became the new Lou Reed.

Before the Velvet Underground there was L. A. and the Eldorados, back when Lou Reed was a student at Syracuse University. His friend Allan Hyman, who had been his friend since third grade, was tasked with getting him to frat party gigs on time. “He’d be asleep under three hundred pounds of pistachio nut shells, because Lou loved pistachios, so I’d have to shake him awake, throw him in the shower, and physically get him dressed,” Allan said. “He would be surly, but he’d play.”

“Lou Reed was a prick,” said Rich Mishkin, the bassist for L. A. and the Eldorados. “He was not the kind of guy who would be nice to people in most circumstances. We got a lot of beer thrown at us over the years.” Rich drove the band around in his tail-finned white Chrysler with red guitars emblazoned on the sides.

“It’s no secret that he has lived as well as walked on the wild side, the demi-world of drugs and violence and despair,” Jane said about Lou Reed. “’Heroin’ and ‘White Light, White Heat’ were two of the most popular songs of his first major group, the Velvet Underground in 1967, the same year of ‘I’m a Believer’ by the Monkees and ‘To Sir With Love’ by Lulu. He is wild, changeable, streetwise, poetic, cynical, and offbeat sensitive, maybe.”

Jane wasn’t wild, although she was plenty streetwise, in a matronly kind of way. “We’re talking about some of the most depraved people in the world,” said Michael Stanley, who played heartland rock ‘n roll for donkey’s years in the Rock Capital of the World. “But with Jane, it was like they were talking to their mom or their grandma. It was, ‘Yes, ma’am’ and ‘No, ma’am.'”

Behind her trademark red-rimmed trifocals and dyed-blonde hair, she was unflappable. She was a fan as well as an advocate of the sound. “Since I was a little girl, I remember my dad, whose name was Pepe, enjoyed Jane’s reviews and would read them to my brothers and me after dinner,” said Callie Paris Rini. “We were music lovers. When the Beatles first came to Cleveland, Jane gave my dad a newsprint plate of them, and I still have it. I still have Jane’s review when Jimi Hendrix came to Cleveland, too. I read her articles whenever I went to concerts in the 60s and 70s.”

The Beatles broke up in 1970. Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and Janet Joplin all died, all three of them at the age of 27. Rock concerts moved from clubs and small theaters to sports arenas. Disco and glitter rock came and went. Jane Scott went to all the shows, even the new wave ones, where guitars were unplugged and synthesizers were plugged in. “I sat next to her for nearly three years of concerts back in the late 70s,” said Rick Weiner. “She would always ask me if I was enjoying myself. Jane stood out like a sore thumb, but once you conversed with her you knew there was a reason she was there.”

Her favorite musician of all time was Bruce Springsteen and her favorite album of all time was ‘Born to Run.’ When she reviewed his show at downtown Cleveland’s Allen Theatre in 1975 she wrote, “His name is Bruce Springsteen. He will be the next superstar.” Before the year was out the Boss was on the covers of Time and Newsweek. At a later Cleveland concert, he dedicated “Dancing in the Dark” to Jane Scott, who was in the audience. “If you can meet Bruce Springsteen, who wants to sit around and play bridge?” she asked tongue in cheek.

When it came to her job, it was the more the merrier. “Jane was the first to welcome me to the news room when I came to Cleveland in 1979 as a Plain Dealer feature writer,” said Janet Gardner. “After I returned to New York, she would call me between sets from the Peppermint Lounge, breathless with enthusiasm. She was a truly ‘The World’s Oldest Teenager.’”

In the 1980s superstars continued to sell out, selling out stadium concerts. Alternative rock emerged. Synth-pop got more and more popular. Dance-pop got hot. Hip-hop popped up. Olivia Newton-John recorded one number hit after another. Jane Scott covered them all. The older she got the younger she got. “I met Jane in 1984 when she was covering a Husker Du show at Pirate’s Cove,” said Rev Recluse. “She was the sweetest, kindest person to everyone and melted this too-cool-to-exist teen hipster’s heart by the encore.” The Pirate’s Cove was in the Flats when it was still a rough-and-tumble place featuring a shot and a beer. There were real shots sometimes down dark back alleys. Olivia Newton-John never set foot there. She kept it in the sugar bowl.

“Jane didn’t critique music,” said Pere Ubu’s frontman Dave Thomas. Pere Ubu was a Cleveland-area avant-garage band. “She reported facts. And, subversively, she demystified the art. She peeked behind the curtain and rooted out the parochial. Every musician sees the media as gullible rubes. Well, Jane just didn’t cooperate. She laid the haughty low with enthusiasm.”

The 1990s saw rap and reggae get popular. Urban-style music blended jazz, soul, and funk. Fusion genres came and went. Jane Scott stayed on top of it, reviewing everything that came her way. If it was going to be a long night she packed two peanut butter sandwiches in her hefty bag.

“I had the privilege of attending several concerts with Jane in the 80s and 90s,” said Emile Knud-Hansen. “It was amazing to watch her interview some covered-in-black with safety pins in the eyebrows teenage rocker. She never judged anyone but gave performers ample time to explain their music. I was surprised to learn that she had never gone to a rock concert as a guest. So, my friends and I took her to see Huey Lewis and the News at the Blossom Music Center. We were in front of the amplifiers, right up front. She was happy in spirit and ruffled in appearance.”

After Jane Scott retired from the Cleveland Plain Dealer and her long-time companion Jim Smith died, her legs started to go bad. She bought a walker and moved into Ennis Court, a small assisted-living facility in her hometown of Lakewood. When she did, Danielle Rose began visiting her, keeping her company.

“I met her at First Church where we were both members,” Danielle said. “I lived up Detroit Ave. and could walk to where she was living. We started car-pooling to Wednesday Testimony Meetings. One summer night going home we were pulled over by a Lakewood cop car.” The policeman was a woman. She asked Jane if she knew why she had pulled her over.

Jane thought for a moment. She fiddled with her hefty bag. She finally said, “No.”

“Your lights aren’t on.”

“Oh.”

“Don’t forget to turn them on and drive safely,” the policewoman said.

Jane had been pulled over in front of one of her favorite ice cream shops. When she noticed the lights were still on in the shop she left the running car where it was and stepped onto the sidewalk.

“Do you want to join us?” Sweet Jane asked the policewoman.

“She loved ice cream. She was just a big kid. Her car knew where every cone on the west side of town could be gotten,” Danielle said.

“Thanks, but I’m on duty,” the policewoman said.

“Maybe next time,” Jane said.

“She had a young spirit but she really shouldn’t have been driving anymore,” Danielle said.

True to her spirit Jane Scott died on Independence Day in 2011. The next month a memorial service was held for her at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which was attended by nearly a thousand people. A year later the museum unveiled a life-size bronze memorial statue of her sitting on a bench and taking notes, created by Dave Deming, past president of the Cleveland Institute of Art. It was permanently installed in the Reading Room of the Rock Hall’s Library and Archives.

All it took to get Jane Scott to sit still in one spot while the beat went on was for the clock to run down. “Walk it on home” is what Lou Seed sang in her ear. There was a hell of a band waiting for her in heaven.

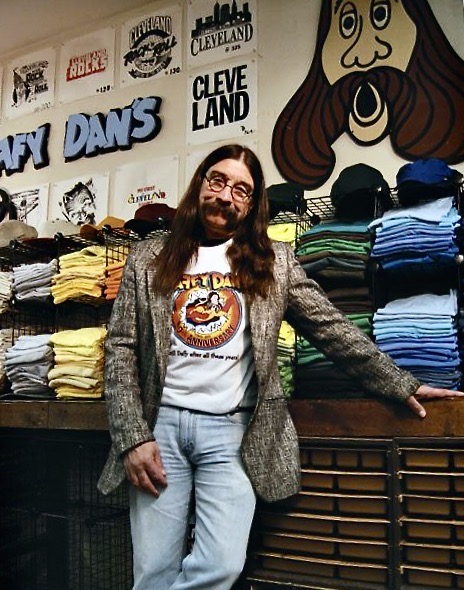

Photograph by Janet Macoska.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Late summer, New York City, 1956. The Mob on the make and the streets full of menace. President Eisenhower on his way to Brooklyn for the opening game of the World Series. A killer waits in the wings. Stan Riddman, a private eye working out of Hell’s Kitchen, scares up the shadows.

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication