By Ed Staskus

There are thousands of restaurants in Cleveland Ohio. Captain Frank’s isn’t one of them anymore. It used to be and when it was it was one of the best places to eat if you liked seafood and Lake Erie waves and wind shaking the building on the E. 9th St. pier. Every so often somebody full of cheer and careless after a hearty meal, or simply drunk as a skunk, drove off the pier into the lake.

“It was always my last stop after a night of drinking in the Flats,” said Nancy Wasen. “Every night I was surprised no one fell off the pier and drowned.” It wasn’t for want of trying.

In 1964 Mary Jane Jereb was 16 years old. She was in a car with her cousin and a neighbor and a driver’s education instructor. “He took us downtown, to prepare for city driving. I wasn’t driving, my neighbor was. He directed her to this particular parking lot.” It was Captain Frank’s parking lot. They drove straight to the edge of the slimy pier. Spray from the Great Lake spotted their windshield.

“The instructor told my neighbor to turn around and head back to Parma. My short young life flashed before me as she pulled into a parking space and backed out and headed home.” They slowly carefully left the dark deep behind.

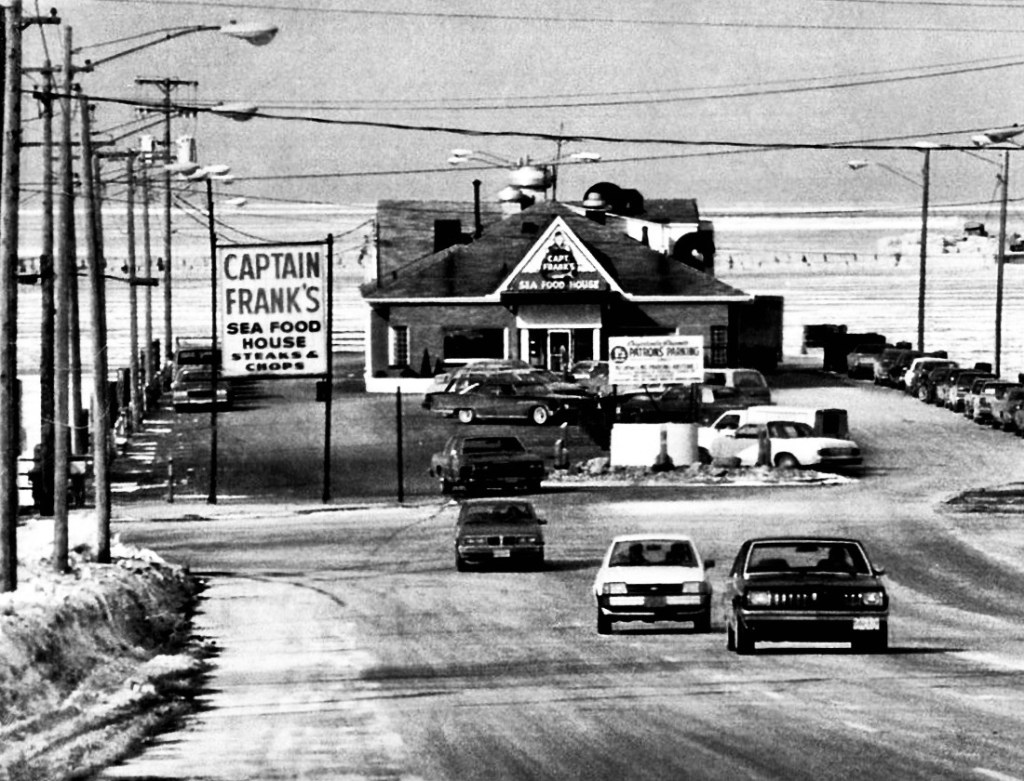

Captain Frank’s was a “Lobster House” or a “Sea Food House” depending on the signage of the year. It changed now and then. There was a panhandler who called himself Captain Frank who hung around outside the restaurant day and night, his hand stuck out. Demoted cops who had kept quiet about hidden rooms in gambling joints and pocketed cash in job-buying schemes were assigned to seagull patrol on the pier, always in the dead of winter. They ignored the panhandler and did their best to walk the chill off. Sometimes they helped the innocent just to stay on the move.

Francesco Visconti was the Captain Frank who ran the restaurant. He was a Sicilian from Palermo whose parents beat it out of Europe the year World War One started. At first, as soon as he could handle a horse, he sold fish from a wagon. After that he operated the Fulton Fish Market on E. 22nd St. He was 40 years old in 1940 and lived with his wife, Rose, a son, as well as three daughters.

He bought a beat-up passenger ferry building on the E. 9th pier in 1953 and opened Captain Frank’s. I was a child living the easy life in Sudbury, Ontario at the time and missed the grand opening. Kim Rifici Augustine’s grandfather was the original chef at Captain Frank’s. “The wax matches he used for flambé caused a fire back in the 1958,” she said. The fish shack burned down. Frank Visconti built it back bigger and better the next year.

By the late 1950s my family had emigrated from Canada to Cleveland Ohio. We lived nearby, but never went to the restaurant. My parents were Lithuanians and ate bowls of beetroot soup and plates of potato pancakes and meat-filled zeppelins at their own table. They didn’t know a Mediterranean Diet from Micky Mouse.

In the Old Country they had feasted on pigs and crows. My mother’s father was a family farmer who kept porkers, slaughtering them himself, and smoking them in a box he built in the attic of the house, the box built around their fireplace chimney. “It was the best bacon and sausage I ever had in my life,” my mother said eighty years later.

They hunted wild crows. “Those birds were tasty,” my mother said. The younger the birds the better. Those still in the nest and unable to get away were considered delicacies. Their crow cookouts involved breaking necks and boiling the birds in cooking oil over a bonfire. They served them with whatever vegetables they had at hand.

Since I was part of the family, I ate with my parents, my brother, and sister. My mother prepared every meal. I ate whatever she made, even the fried liver and God-awful Baltic headcheese, although we never, thank God, had carrion-loving crows. Even if I had wanted to go to the Lobster House, I didn’t have a dime to my name

Captain Frank’s boomed in the 1960s and 1970s. There were views of the lake out every window. There was an indoor waterfall. If you had water on the brain, it was the place to be. The food was terrific. Judy Garland, Nelson Eddy, and Flip Wilson ate there whenever they were in town doing a show. The Shah of Iran and Mott the Hoople partied there, although not at the same time. They weren’t any which way on the same wavelength, other than under the spell of Captain Frank. He never asked them to leave, no matter how late it was.

There was a luncheonette behind the restaurant that doubled as a custard stand in the summer. When the Shah or Mott the Hoople stayed later than ever, they could sit in the back in the morning in the breezy sunshine with a cup of custard while lake freighters went back-and-forth. “I never went inside Captain Frank’s, but I remember the ice cream shop in the back well,” recalled Bob Peake, a homegrown boy who was a frozen sweets connoisseur.

Frank Visconti was a made member of the Cleveland Mob. His criminal record dated back to 1931, including arrests for narcotics, bootlegging, and counterfeiting. The restaurant was frequented by high-echelon hoods and low-minded politicians alike. Many criminal family meetings were held there.

“It was the hangout for Cleveland Mafia Enterprises,” said Tom James on Cleveland Crime Watch.

Longshoremen went to Kindler’s and Dugan’s to drink before and after work, but between their double shifts went to Captain Frank’s for power shots. When they were done it was only a short walk back to the docks. When the weather was bad, they were warmed up and sobered up by the time they clocked back in.

The restaurant was a football field’s length from Lakefront Stadium, where Chief Wahoo and the Browns played. The ballpark sat nearly 80,000 fans. The Indians were always limping along, their glory days long gone, but the Browns were exciting, and on game day crazy loud cheering rocked the windows of the restaurant. Cold biting winds blew into the stadium in spring, fall, and winter. In the summer under the lights, swarms of midges and mayflies sometimes brought baseball games to a standstill.

In 1966 the Beatles played the stadium and after that the Beach Boys, Pink Floyd, and the Rolling Stones showed up to rock the home of rock-n-roll. It was a walloping paycheck for a night’s work. In the 1980s U2 brought its big show to town, raking in millions singing about lovesickness and hope. Every so often they threw in something about social injustice.

Even though I was grown-up by the 1970s, I still didn’t dine at Captain Frank’s. I was living in a rented house in a forgotten part of town, and it was all I could do to feed myself at home. I didn’t have pocket money to eat out. When I finally joined the way of the world and could afford to go whenever I had some spare change and wasn’t too tired from working with my hands all day, I ate out. Most of my friends were already racing to the top. I was starting at the bottom.

There was a kind of magic eating at Captain Frank’s at night. I watched the lights of ships making their way slowly into Cleveland’s harbors while munching on scampi and warm rolls swimming in garlic butter. They served steaks the cooks seared, but the seafood was usually just threatened with heat and served. That’s why it was good. Students from St. John College on E. 9th and Superior Ave. walked there to have midnight breakfast because it was nearby and substantial

The Friday night in September 1984 my friend Matti Lavikka and I treated my brother to dinner on his 31st birthday at Captain Frank’s was almost the last birthday he celebrated on this earth. We didn’t know Frank Visconti had died earlier that year, but in the car on the pier after dinner we thought my brother was dying. He was gasping for air. The dinner had been very good, but he looked very bad. We were afraid he might end up swimming with the fish.

He was getting over a marriage to a Columbus girl that had lasted 56 days. We picked him up in Mentor, where he was living alone, and went downtown. It was a starry late summer evening. We ordered a bottle of Chianti, some pasta, and lots of shellfish. We didn’t know, and he didn’t know, that he was allergic to shellfish.

“I don’t know why, but I hardly ever eat fish,” he said. “It doesn’t usually agree with me.” Our dinner at Frank’s that night included scallops, oysters, shrimp, and lobster. He might not have been allergic to all of them, but he was allergic to one of them, for sure.

Halfway through coffee and dessert, which was sfogliatelle, layers of crispy puff pastry that bundle together in a lobster-like way, he was itching, wheezing, and his head was swelling. His lips, tongue, and throat were like silly putty. He was breaking out into hives. He was getting dizzy and dizzier. It was like he had eaten a poisoned apple.

Shellfish allergy is an abnormal response by the body’s immune system to proteins in all manner of marine animals. Among those are crustaceans and mollusks. Some people with the allergy react to all shellfish. Others react to only some of them. It ranges from mild symptoms, like a stuffy nose, to life-threatening.

Matt was a fireman and paramedic in Bay Village. Looking at my brother he didn’t like what he was seeing. We frog-marched him to the car and made a beeline for the nearest hospital. Matti put the pedal to the metal. The Cleveland Clinic wasn’t far, and we had him at the front door of the emergency room in ten minutes. Five minutes later a doctor was injecting him with epinephrine and a half-hour later he was his old self.

“Thanks, guys,” he said when we dropped him off at his bachelor pad in Mentor. He staggered away to bed.

After Frank Visconti died the restaurant limped along. The service and food got worse and worse. The tables and chairs and walls looked like they needed to be scrubbed down. Fewer and fewer people went downtown for any reason other than work. I was working downtown near the Cleveland State University campus, where Matt and I had started a small two-man business. One evening when I got off work, I called my girlfriend and invited her to dinner at Captain Frank’s. I had seen her eat buffets of seafood. She had a hollow leg. I knew she wasn’t allergic to any of it. When we got there, however, the pier was dark in all directions. There were no parked cars in the lot and no lights in any of the windows.

Rudolph Hubka, Jr., the owner the past five years, had given up the ghost and declared bankruptcy in 1989. Nobody said a word. Hardly anybody noticed. The building was demolished in 1994. The only thing left was dust and litter blowing around in the wind.

We drove to Little Italy and snagged a table at Guarino’s, a woman out front pointing the way. Sam Guarino had died two years earlier, but his wife Marilyn was carrying on with the aid of Sam’s sister Marie, who lived upstairs and helped with the cooking in the basement kitchen. “Marilyn sat in front, and she was like the captain on a ship, making sure everything was just right,” said Suzy Pacifico, who was a waitress at the eatery for fifty-two years.

We had a farm-to-table dinner before there was farm-to-table, red wine, and coffee with tiramisu. Mama Guarino asked us how we liked the cake. We told her we liked it very much. We didn’t see any fishy characters. When I drove my girlfriend home that night we were both happy as clams.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”