By Ed Staskus

“Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got, ‘till it’s gone.” Joni Mitchell

Starting early in April, lights start blinking back on in stores inns restaurants and businesses of all kinds on Cape Cod. Hiring ramps up for cooks, waiters, waitresses, cashiers, retail associates, merchandisers, front desk agents, landscaping, cleaning services, and even at local airports who park and fuel aircraft. The Sagamore Bridge puts on its best welcome back smile.

Even though snowfall is slight on Cape Cod, whatever there is of it melts as the weather gets warmer. Purple-blue hyacinths and bright yellow daffodils start to open. In Wellfleet, which is between Orleans and Provincetown, where almost everything shuts down for the winter, almost everything opens up again in the spring. Except when it doesn’t.

It was early in April when Joe Wanco and his family, wife Laura and daughters Michelle and Jodie, made it known that their Lighthouse Restaurant would not be opening for the upcoming season. The iconic mid-19th century building in the middle of town on Main St. groaned.

“After many years, many employees, many building renovations, many blueberry muffins, pints of beer, and Boston sports championships, it has been decided it is in the best interest of the family that we no longer operate as a business. This is not a decision made overnight or without extensive consideration. Forty years is a long time and even longer in restaurant years.”

“Oh, man, this is sad,” said Molly MacGregor. It being springtime on the Outer Cape, dark gray clouds rolled in and filled the sky. “This is worse than closing down Town Hall,” said Steve Curley. “I want to scream, NOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!” screamed Heidi Gertsen-Scheck.

Forty years in the dining room trade is like four hundred in dog years. It’s a challenge as well as a slog. If you like falling jumping being pushed off the deep end, operating a watering hole is for you.

Even if your menu is coherent and priced appropriately, and the tables are set nice and neat, and the ambience is what your customers like, but the customer service is sour, customers will remember and go elsewhere. Even if management is ahead of food and drink costs and keeps labor costs manageable, if they don’t notice nobody is asking for slimehead, and don’t take it off the menu, they’re stuck with a freezer full of slimehead. On top of that, even if the grub is outstanding, the staff trained and civil and ready to go, if the front man is slow-mo marketing his restaurant, he ends up with a half-empty restaurant.

“You have had a great run,” said Jim Clarke, who owned the Lighthouse from 1968 to 1978. “I still have memories and nightmares from those years. I wish I had a nickel for all the muffins I baked.”

The Lighthouse was a local seafood eatery, with arguably the best oyster stew between Cape Cod Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, a local sports bar and grill where the Patriots Red Sox Celtics ruled the roost on the flat screens. It was a local dive bar with two-dollar cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon and Cape Cod bands livening up the joint year after year.

“You guys have been a bedrock of this community,” said Sam Greene. “Main Street won’t be the same,” said Donna McCaffery. “We started almost every vacation in Wellfleet at the Lighthouse, starting in 1989 when my now husband met my family there for our vacation-starting breakfast,” said Laura Wardwell.

Six White House men came and went, while another one got stuck in traffic with a flat tire and only Twitter to keep him company, from the time the Wanco’s landed on Main St. Townspeople and tourists grew up with the Lighthouse. Others were born and had to find out for themselves, peeking in through a window. “I grew up with stories about the Lighthouse before I even knew what it was,” said Amy St. John Ramsdell.

“Our five children grew up having breakfast at the Lighthouse every Sunday after mass,” said Jodi Lyn Deitsch-Malcynsky. “Your family was always inviting and gracious and fun! Our summers in Wellfleet will be forever changed.”

“I remember parking my bicycle out front and coming in for a Cherry Coke,” said Matt Frazier, years before he became their trash hauler and recycler. “An extra special thank-you for always treating our crew with snacks and beverages during and after Oyster Festival.”

The menu wasn’t encyclopedic, the prices weren’t an arm and a leg, even though the plates were chock-full, and the always hot food was more than good, often very good. “The best scallops in the world, as good as Digby, Nova Scotia,” said a man from Boston. “What’s more to say?”

“I can’t say enough about the Cod Ruben,” said a man from Westfield. “They had a great selection of beer. The service was awesome.” He was crestfallen when he heard the news. “Where am I going to get a good Cod Reuben now?”

“They happened to have lobster dinners on a special, super fresh and tender,” said a woman from Worthington. “They were the best lobster dinners we had all summer.”

The Lighthouse was the only restaurant on the Outer Cape without a front door. There were two side doors, and plenty of windows to sit at and watch the world go by. “Here’s to missing the big picture,” one man said to another, sitting at the bar one September morning, over hearty breakfasts and Bloody Mary’s, their backs to the front window. The bar sat about a dozen and the front room and side room tables sat forty or fifty. The floors were hardwood. There is a big skylight in the beamed tilted ceiling of the side dining room. It isn’t a small place, but it isn’t a big place, either. It was always lively and got even more lively at night.

“When I was younger it was our breakfast place,” said John Denninger. “As I grew older it was my place to get a drink. When I decided to move here the Wanco’s made it feel like home. I could not have found a better place to hang out.”

A red and white replica of the red and white Nauset lighthouse is on the flat roof of the front room. “The lighthouse does great service, yet it is the slave of those who trim the lamps,” observed the writer Alice Rollins. It doesn’t go looking for passing ships in the night. It just stands there with its big bright light on. Lighthouses are always lighthouses in somebody’s storm, especially if the fish is pan-fried just right and the beer is cold.

The Wanco’s came from New Jersey in the late 1970s. They partnered with a friend of theirs in the restaurant so they could “try our hand at a small business in a seaside town in an expression of our own American dream.” Their partner retired after ten years, but the Wanco’s kept the fireplace stoked, carrying on. “It was our family providing a watering hole, meeting place, warm meal, cold beer, loud music, local gossip, friendly banter, and a smiling face.”

Besides everything else, who wants to lose a smiling face? There aren’t a great abundance of them to begin with. “Ah, Jaysus,” said Jenifer Good. “It’s too much!”

Owning and operating a restaurant isn’t the same as going to work. It’s more like hard work. Many people start work by checking their e-mails. So do many restaurateurs. Many people check their e-mails all day. Most restaurateurs don’t. They don’t have time. There are too many other things to do.

After they’ve turned on the lights and checked their mail in the morning they do a walk-through of the restaurant, note what needs to be cleaned repaired replaced, start receiving orders, start food production, say hello to arriving cooks and staff, last minute scrambles because someone is sick hungover missing, breakfast service, take a break, lunch pre-shift, lunch service, move on to more food production, staff meal, dinner pre-shift, dinner service, clean up, wipe down, go over the day’s receipts, stay on top of staffing for tomorrow, and fit in balancing the checkbook, making payroll, checking inventory against reality, making a list of purveyors to talk to, and finally, locking up for the night

All of this without swearing too much at staff customers passersby and loved ones. Not that working at the Lighthouse wasn’t a happening, spiced by curses out of left field. “Working there was always an adventure,” said John Dwyer.

“My first waitressing job was 40 years ago here,” said Gina Menza. “I was terrible, but they kept me on. Some crazy memories of living upstairs, sitting on the roof to watch the parade, and sneaking into the drive-in rolled up in a carpet in the back of the company van.”

The Wellfleet Drive-In has been around since 1957. It’s one of only a few hundred drive-ins left in the USA. Vans and pick-ups back in so the crowd packed inside them can see the screen.

“What I remember is living in the upstairs apartment while working at the Lighthouse at my first job, smashing my head into the tables while running from the kitchen to the dining room, creamy dill salad and the best pickles on the planet, working down in the bakery, and years later to many post-shift beers,” said Jacqueline Stagg.

“My most fun job ever,” said Kelly Moore. “Endless pre-games and endgames, situations, life lessons with Pill Bill, meltdowns, bike stealings and returnings, hurricane parties, skinny dipping team meetings, Wall of Shame, family breakfasts, jam sessions, chats with Thomas, high society, beer pong tournaments, roof top nights, off-season regulars, and Mexican meltdowns with Slammo. I will never forget mista sista kissa.”

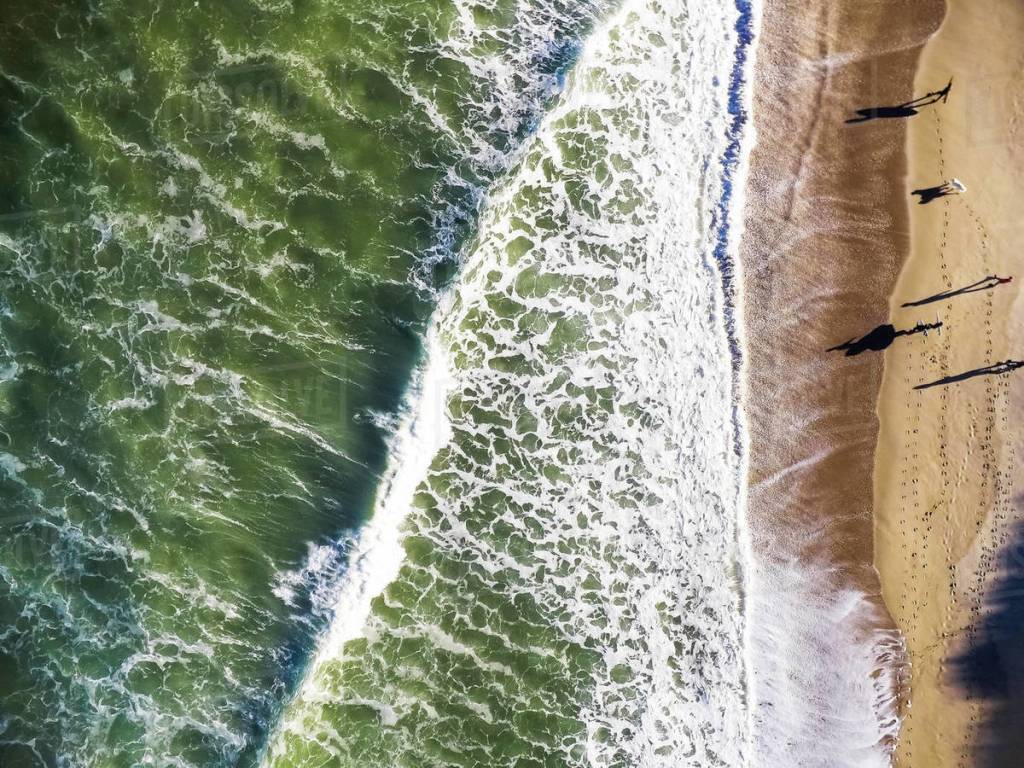

Communities are built around their city halls, schools, and businesses. Even though the Outer Cape is known for its guidebook attractions, sun and sand whale watching art galleries seafood summer theater, Provincetown, the Cape Cod Rail Trail, and the National Seashore, its essence is in its smaller neighborhoods and places.

“They were the center beacon of our town,” said Chris Eize of the Sacred Mounds. “When we became the house band, we became part of the place.”

Most bands that played at the Lighthouse played where the music sounded consistently better than it should have sounded, resonating better than the written notes and the acoustics, and from Funktapuss to the Sacred Mounds they always lit up the venue. “The Super Scenics always had a blast playing there with our gracious hosts the Mounds and the Lighthouse” said Jeff Jahnke, “Thanks and cheers!”

“We got to know Michelle and Jodie on an intimate level of trust, honest communication, and friendship,” said Chris, the front man of the Mounds. “I loved how Jodie didn’t really have a filter, and you knew exactly what she was thinking, because she would tell you, whether you liked it or not. We enjoyed the after-show drinks and reflections with Michelle, and that openness will live on with appreciation and fondness.”

There is always a lot of camaraderie in restaurants, everybody working closely together, all in around the chuck wagon. “The restaurant business, even in the most stable of markets is, frankly, exhausting,” said Joe Wanco. “It’s an ever-consuming extra member of the family. There are no restful nights, even with the help of your favorite tequila.”

It is a consuming undertaking because of the long days, most of it on your feet, and the competition inherent in the undertaking. The restaurant business is massive, with more than one million restaurants coast to coast. The chances of making it even two years are slim. Most eateries close in their first year. Three out of four close in the next three to five years. Making it four decades is Bunyanesque.

The Wanco family put their heart and soul into their work. Staying the course means staying steadfast. “Wow, 40 years, that’s awesome,” said Katie Edmond.

“You and your oyster stew are going to be greatly missed,” said Rob Cushing. “Joe and Laura, enjoy your well-deserved retirement,” said Virginia Davis. “You have served the town well.”

It works both ways, coming and going, since Main St. is not a one-way street. “We are eternally grateful for the many years of support from our loyal clientele, especially our year-round community,” said the Wanco family, signing off. “Good luck, cuz,” said Joyce Fabiano to the leave-taking. “We sure are going to miss you all,” said Mike Deltano.

“What I want to know is how will I ever now find my children when I get to Wellfleet since the Lighthouse is closed?” asked Judy Sherlock. “Look for them at the town library?” She thought better of spitting out “Hah!”

The Wanco’s were the food and drink keepers for a long time. The lights of our favorite places go on and off over time. Every now and then they need a new minder. What Main St. in Wellfleet needs now is a new barkeep to fire up the lanterns at the local public house again, like the New Jersey transplants did forty-some enterprising years ago.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”