By Ed Staskus

Uncle Ernie was no fool. He knew this moment had been waiting to happen for a long time, even though it came out of the blue. He wasn’t fooled by the nondescript car that slid up to the curb across the street. He wasn’t surprised, either, that the two men in the car didn’t get out right away. He knew they were getting their bearings and that he had enough time to do what he had practiced doing when the time came. He got all the cash he kept in a Premium Plus cracker tin in the kitchen and stuffed it into his pants pockets. There was more than $78,000 of it, most of it in one hundred dollar bills. His pants bulged on both sides of his crotch with the wads of cash.

He grabbed a pack of Pall Malls and put his bucket hat on. He slipped a belly gun into his back pocket. It was a Smith & Wesson Model 10. It was illegal to carry a concealed weapon in Ohio, but that was the least of his concerns. He quickly went into the basement, set an alarm clock wired to a bundle of dynamite, and went out the kitchen door. He stood still on the back porch for a second. He walked down the alley. A cat on top of a fence post watched him. His car was parked in a rented garage at the end of the alley. The widow who lived there didn’t have a car and appreciated the monthly rental money. He walked to the garage, unlocked it, unlocked his car, pulled it out, locked the garage up again, and drove away. He would miss his house, but he didn’t want to end up in the big house, where he knew his life would be worth nothing. It would only be worth something to the men who would want to kill him once they found out who he was. He had no doubt they would find out.

Frank Gwozdz and Tyrone Walker watched the house for five minutes from their Crown Victoria. The front porch was in shadows. No lights were on in the windows. There was no blue flicker of a TV. Tyrone thought nobody was at home and suggested they come back in the morning.

“Take the back door,” Frank told him, ignoring his suggestion. “Don’t do anything unless somebody comes out. I’ll go in the front door.”

“What if the door is locked?” Tyrone asked. “We don’t have a warrant and this Earnest Coote doesn’t have a record.”

“Like I said, I’ll take the front,” Frank said.

The alarm clock ticked down toward the minute it had been set for. Uncle Ernie had set it for ten of them. Zero hour was coming up fast. As the timer got to where it was going Tyrone was standing behind a line of shrubs at the rear of the backyard. Frank was walking up the front walk. When the clock struck its appointed hour and the contacts made contact, the house blew up.

The blast catapulted both Frank and Tyrone backwards. Frank landed hard on his butt, partly breaking his fall with his hands. It happened fast. The breath was knocked out of him. Tyrone was thrown backwards into the chain link fence that the shrubs were a border for. The fence absorbed then repulsed him. He bounced off the chain links and landed on his face, splitting his lower lip. The house blew up, but not outwards, saving Frank and Tyrone and the houses on both sides of Uncle Ernie’s house from too much damage. Frank scurried on his hands and knees away from the house to behind a maple tree on the tree lawn, gasping for air. Tyrone stayed on the ground. He sheltered his head with a garbage can lid. When shards of glass and splintered wood stopped raining down on them, they both stayed where they were, hoping the next shoe wouldn’t fall. The house fell in on itself. A gas line exploded and the clapboard caught fire.

Five minutes later an engine truck from Fire Station No. 31 pulled up. The firemen began to spray water on the house with their deluge gun. They left their ladders on the truck. The second floor of the house didn’t exist anymore. When their water tank ran dry they switched to the uncurled hoses which they had attached to a hydrant. A patrol car pulled up, followed soon enough by two more of them. The policemen stood to the side. There wasn’t anything for them to do. All the neighbors who had rushed out of their houses stayed at a careful distance gaping at the fire.

After an East Ohio Gas truck arrived, and the gas line had been shut off, the firemen finished their work. Before long all that was left of the house was a smoldering heap of charred wood and rubble. The mess had once been a place, but it wasn’t anymore. Frank and Tyrone stood in the street leaning on their Crown Victoria. Other than some cuts and bruises, neither man was hurt overmuch, although Frank had a gash on the back of his hand. He knew it needed stitches. He wrapped a handkerchief around it to staunch the bleeding.

“Come on,” he said. “Let’s get over to Mt. Sinai.”

“Mt. Sinai?”

“The hospital, not the mountain. Right now, I need a doctor, never mind Moses. They can look at your lip, too.”

An hour later, his hand sewn up and a tetanus shot working its magic, Frank drove the few minutes to Uptown at E. 105 St. and Euclid Ave. He needed to catch his breath. He needed food. He needed a drink even more. He looked around for a place that might have both.

“Uptown used to be Cleveland’s second downtown,” he said as Tyrone licked his sewn up swollen lip and took in what amounted to the sights.

“What happened to it?”

“The race riots and Winston Willis happened to it.”

Uptown started life as Doan’s Corners when Nathaniel Doan opened a tavern and a hotel in the early 1800s. They were built because the spot was a stagecoach stop between Cleveland and Buffalo. In the early 1900s the Alhambra Theater opened. It was a vaudeville house until it became a movie house. It sat more than a thousand in the mezzanine and nearly five hundred in the balcony. There was a pool hall next door. The young Bob Hope hustled nickels there playing the new game of nine-ball and cracking wise through misunderstandings. He was good at pocketing the number nine ball on the break, winning the game outright. The Alhambra was followed by restaurants, clubs, and more theaters. By mid-century the Circle Theater was hosting Roy Acuff and his Grand Ole Opry and Keith’s 105th Street Theater was showing first-run motion pictures on a new wide screen.

Ten years later Uptown started going downhill. When it did it went down fast, picking up speed on the wrong side of the hill. The neighborhood went from mostly white skin to mostly black skin. The Towne Casino had already been bombed in the 1950s. The reason was the popular music club attracted an interracial audience. The city’s grand dragons in their civil defense shelters didn’t like anything interracial. The Hough riots and Glenville shootings sealed Uptown’s fate. Nobody liked bullets flying. White flight sped up until there were almost no whites left. Those who stayed, stayed inside their homes behind closed curtains, watching the value of their properties fall to nothing. Winston Willis stepped into the breach, snapping up as many holdings as he could, opening penny arcades and adult bookstores. The Performing Arts Theater became the Scrumpy Dump Cinema. The Scrumpy Dump showed low-budget B movies about the sewer looking like up to their sad sack stars.

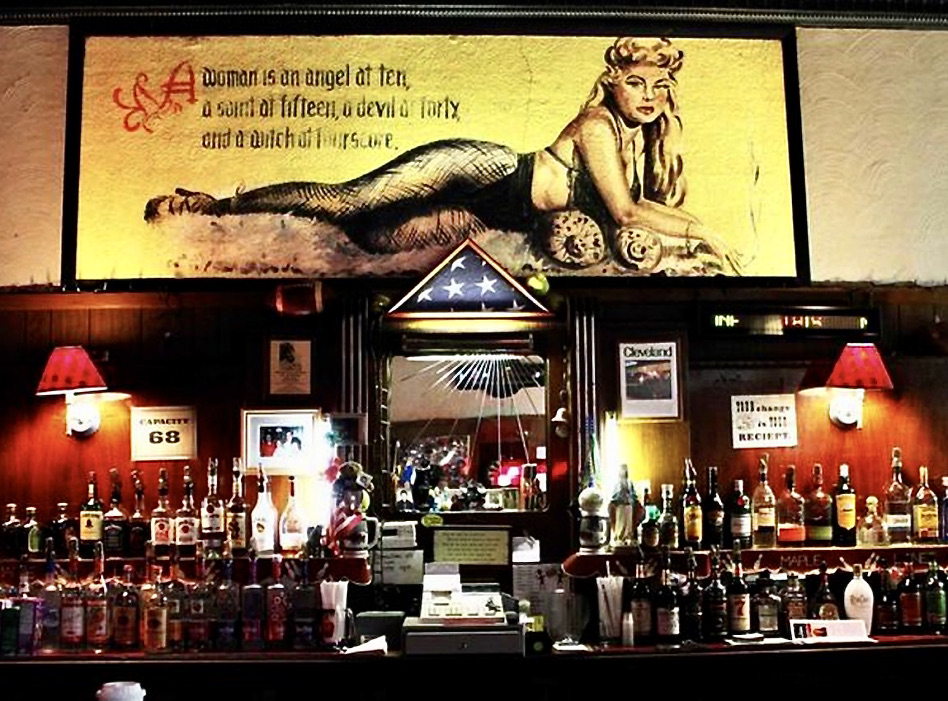

Frank rolled his side window down and propped his elbow on the rim of the door. Nothing looked inviting. Everything looked like a greasy dump. He swung the wheel, took Liberty Blvd. to Larchmere Blvd., and when he got to the Academy Tavern parked on E. 128 St. He and Tyrone walked to the bar. It was a two story brick building. The electric sign read, “Food & Liquor Since 1939.” The front door was catty-corner to the corner. A dark green awning was over the door. The police detectives went inside and found seats at the far end of the bar. Frank ordered a cheeseburger with a fried egg on top and a side of pickles. Tyrone had the same except for the pickles. He didn’t like anything brined. He ordered mashed potatoes. They each had a glass of Falstaff on tap.

“What do you think happened back there?” Tyrone asked while they waited for their food.

“I think Earnest Coote saw us coming,” Frank said. “I don’t think it was an accident. He either rigged something up fast, or had it set up beforehand. I’m guessing he had it set up, like a fail-safe. I think he went out the back. If we had gone in a minute-or-two sooner we wouldn’t be here talking, but we didn’t, thank God. I don’t want to be laid to rest in the Badge Case before my time. I’m sure you don’t either.”

“You think he blew his own house up?”

“That’s what I think happened, yes.”

“Who does something like that?”

“Somebody who has a good reason for doing something like that. The Bomb Squad will fill us in on what happened. I wouldn’t be surprised if our man-made bombs in the basement.”

“How’s the hand?” Tyrone asked.

“It doesn’t hurt, yet. It’s the pills the doc gave me working their magic. He had to stitch it up because the cut was two inches long and jagged.”

“How many stitches?”

“Seven.”

“Ouch,” Tyrone said as their cheeseburgers were delivered. “At least it’s your left hand.”

“I suppose, although I’m left-handed,” Frank said.

They ate in silence. The bar was half-empty. The Cleveland Indians were losing another game in living color on a TV behind the bar. Herb Score and Joe Tait were broadcasting the bad news. When the police detectives were done eating they finished their glasses of Falstaff. Frank paid the bill of fare for both of them. They left the Academy Tavern and walked up East 128 St. Approaching their Crown Victoria they saw two Negroes huddled beside the car. It was parked under a leafy tree. One of the men was fiddling with the driver’s side door. He had a cleft chin. The other man was the watchdog, except he was busy watching his partner getting nowhere. Both of them had one-track minds. Neither of them saw the jim-jams coming.

“It looks like those soul brothers are trying to borrow our car,” Frank whispered.

“Does that mean you want me to take care of it?” Tyrone whispered in his turn.

“You’re soul brother number one in my book.”

“All right, give me a minute,” Tyrone said, reaching for his badge to display as he started walking towards the two men. He believed in law and order by the book.

Frank reached for the roll of dimes in his pocket, making a fist around the Roosevelts. He tucked his left hand away in his pants pocket for safe keeping. He squeezed his right hand, getting a good grip on the dimes. He believed in getting the job done right. He kept his eyes on the big man who was doing the fiddling with the lock. Frank hoped to God he didn’t break anything in his hand when he sent the man nosediving.

He went dead set towards the thief at the car door. There was going to be trouble when he got there. He would have preferred believing the best of what he was seeing happen, since it would save toil and trouble. Oh, hell, I might as well get it over with, he thought.

Excerpted from the crime novel “Bomb City.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Bomb City” by Ed Staskus

“A police procedural when the Rust Belt was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. It gets personal.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication