By Ed Staskus

A commonplace of most yoga advice is the advice to let go of expectation, judgment, and competition when stepping on the mat. The importance placed on themes of tolerance, cceptance, and non-competition is round-the-clock, streamed from beginner classes to advanced asana practice.

On the web sites of many studios, under headings like Yoga Etiquette, is the injunction: “Leave your ego at the door. The yoga mat has no space for your ego, competitiveness, or judgment.” The community class teacher at our local big box studio is fond of saying, “It’s your practice, not anyone else’s.” It’s likely every yoga teacher in America reworks this refrain day in and day out.

Whether the no competition no judgment message is a viable message in our world, driven as it is by ego and judgment, and an everyday workaday world of going for the dollar peso euro yen gold, is between sixes and sevens.

Themes such as moving forward, continual progress, and goals are the modern mantra, not non-competition and non-judgment. The way we live today is nothing if not teleological, so that we are always looking for the cause and purpose of all we make happen, of all we do.

It seems naïve to posit the physical exercise yoga has become as a special case non-competitive activity in the western world, the font of the rat race. Western culture is defined by strife and competition, from our classical past to the way we live now. Everybody gets nervous before a competition, whether it’s a Spelling Bee or the Olympics. They get competitive, too.

Doing warrior pose in the middle of your brain in the middle of the yoga room in the middle of the after work A-Team crowd ain’t any different. Nobody wants to be slam-dunked on.

We are judged and graded from the time we step into school, from tykes in kindergarten through college. The better we do in school the higher the status we carve out for ourselves, until finally carving out a better job when we go out into the working world.

Our marketplace economy is predicated on struggle and competition. We are either making more money than the next man, and so are successful, or we are making less, and so unsuccessful. How much money we make determines how and where we live, our luxury brands, to the better schools we send our children to.

Materialism and its many benefits is a deeply ingrained point-of-view in the western world.

Today’s cultural icons and heroes are businessmen, politicians, and athletes. Follow the money, follow the front page, follow the parade.

“The business of America is business,” said Calvin Coolidge almost 100 years ago. The New Gilded Age has brought President Coolidge’s maxim to life. The ethics involved in the business of making money are subservient to the making of money itself, because losing money is a failure that puts right and wrong to shame.

Politics is only occasionally about doing the right thing. It is necessarily about winning and losing, from debating and campaigning to making your ideology the ideology that matters. The upper hand trumps conscience and scruples among thousand dollar suits without a drop of human kindness in them.

Sports are arguably the passion of our times, from children’s CYO leagues to pro teams playing in stadiums seating tens of thousands. Up to 16 million people may practice yoga in America, but Division 1 college basketball and football attract 70 million paying fans between them, while the four major pro sports draw more than 140 million through the turnstiles every year.

Sports on TV are ubiquitous. More than 127,000 hours of sports programming were available on broadcast and cable TV in 2015. Americans spent more than 31 billion hours watching balls bounce in all directions, sometimes through the net or over the goal, more often not if their home team was hapless.

The average American watches a total of 5 hours of TV a day. The average American never sets foot on a yoga mat. They pay an arm and a leg to watch other people pretend to be super heroes. The mainstream culture isn’t interested in his or her own unified state of mind.

“What the hell does that mean? What does it cost? What’s in it for me?” they ask.

It has been estimated that yoga is a 6 billion dollar business, but that pales in comparison to the college and professional sports team industry, comprising more than 800 organizations with a combined net worth and annual revenues in the hundreds of billions.

Many Americans are intimately bound up in the winning and losing of their home teams. Late in the 2007 season, when the luckless Cleveland Browns were having some success and threatening to go to the NFL playoffs, a large local studio full of men and women at the end of a weekend yoga class unabashedly chanted OM three times for the team, hoping for God’s sake some psychic energy would rub off on the players for that night’s big game.

“The person who said winning isn’t everything, never won anything,” says Mia Hamm, two-time Olympic gold champion.

In the event, the yoga gods played their own little private joke on the fans. Even though the Cleveland Browns won the game, they lost in a statistical tie-breaker to another team and failed to make the playoffs.

How did yoga become a supposed non-competitive activity in our world, a world defined and bound by competition, especially since in its birthplace many define it as a sport? In the sub-continent where it all got started yoga has had a competitive aspect to it for more than millennia.

“Yoga sport has been a traditional sport in India since more than 1,200 years,” said Yogasiromani Gopali, executive director of the World Yoga Council.

“Yoga sport is holy sport in our holy land with our holy yoga. All the yoga ashrams have yoga competition,” said Swami Shankarananda, a supporter of the World Yoga Foundation.

“Yoga competition is an old Indian tradition,” said Bikram Choudbury. “It’s a tremendous discipline – a hundred times harder than any other competition.”

Three for three is the trifecta, the original recipe, extra crispy, and Colonel Choudhury’s special.

The European Yoga Alliance organizes an annual European Yoga Championship and the International Yoga Sports Federation hosts an Annual World Yoga Championship. In the United States yoga tournaments have sprung up nationwide, from the Annual Texas Yoga Asana Championships to the New York Regional Yoga Championships.

Writing in Vanity Fair about the New York event, Anna Kavaliunas observed. “I learned you can win at yoga, a practice that is traditionally considered to be more spiritual than competitive.”

Some variations of yoga seem competitive by nature of the practice itself.

“Since its inception in the mid-twentieth century some of Ashtanga’s great masters pitted the most gifted students against one another to see who would perform the absolutely most difficult poses,” said Marcia Camino, a teacher of Amrit Yoga and a studio owner in Lakewood, Ohio.

“Iyengar Yoga demands so much mental attention to the alignment of the body that built into these classes there seems to be a drive for perfection,” she said. “Some systems like Power Yoga are overtly muscle-focused and it makes sense that one could easily engage the spirit of competitive sports when practicing them.”

At Bikram Choudbury’s Yoga College of India in Los Angeles, classes often come to a dead stop as everyone breaks out into applause for a pose executed especially well. “Bikram Yoga is not only challenging, it’s also gratifying to the ego,” said Loraine Despres, who has written about the once-copyrighted practice.

Maybe Bikram Choudbury has his finger on the pulse of what yoga is really all about. The 2014 World Championship of Yoga Sports was held in London, attracting contestants from more than 25 countries. The 2016 event was staged in Italy.

The Choudbury’s, Bikram and Rajashree, his wife, themselves both former all-India yoga champions, believe yoga should qualify as an Olympic sport for the 2020 summer games in Tokyo.

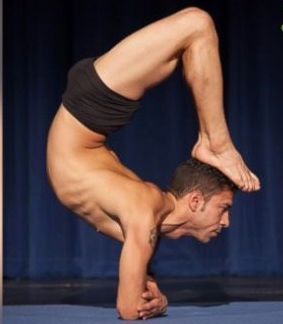

“I strongly believe that yoga has what it takes to become an Olympic sport,” said Joseph Encida, a former international champion. “The skill required is strongly comparable to that of an elite gymnast.”

“There is so much strategy, mental power, physical precision, and control that goes into the sport that I don’t see it any different than curling, skiing, or diving,” said Gianna Purcell, who placed fourth internationally in 2012-13.

It is uncertain how far gung ho yoga will get with its hopes ambitions dreams.

“The Olympics are looking for events that play well on television. If you had combat yoga, maybe that would have a better chance of making it, ”said David Wallechinsky, an author and Olympic expert, in a BBC interview.

Not everyone agrees that competition is good for the practice.

“I don’t think it should be competitive,” said Tara Fraser, of London’s Yoga Junction. “Competing is not embedded in yoga’s philosophical framework and makes no sense if you want to achieve self-realization.”

Michael Alba, a teacher in Boston who also instructs at the Brookline Ballet School, said competition limits and stereotypes the practice. “It perpetuates the idea that yoga is for the lithe-bodied contortionists. One of the challenges of yoga is to be less competitive.”

Competition and its complications are apparently one of the reasons more women than men engage yoga on even a physical level. According to Yoga Journal women make up 72% and men only 28% of the people who practiced in 2016. The two most important reasons men cite for not taking up yoga are a lack of interest in the quiet, non-competitive aspects of the practice and a fear of embarrassment or failure.

Which begs the question, is yoga competitive, or not, and do men want to compete, or not?

Competition problematizes yoga at its most accessible level, which is what goes on on the mat. A goal-oriented approach contradicts what even tournament competitors like Luke Strandquist, a Bikram Yoga instructor in New York City, seem to believe. “As a teacher, it’s the opposite of what I’m always telling my students, that you’re here to practice your yoga, and it doesn’t matter what anyone else is doing.”

Setting one’s sights on doing what the man you see in the perfectly balanced headstand on the mat next to you is doing, or your sights on becoming the mediated image of the slim and strong young woman you’ve always wanted to be, turns the practice away from its focus on the values of self-acceptance and inner growth and turns it into monkey see monkey do.

“Competition exists in the yoga classroom when we see students trying to outdo each other,” said Marcia Camino.

“It’s also there when students struggle to best themselves, their latest efforts, on the road to yoga advancement. That said, there are many systems that balk at the notion of competition, because the focus of real yoga, claim these systems, is inward.”

Separating yoga exercise from the rest of yoga is like separating chaff from wheat and taking the chaff home.

“Unfortunately, yoga has been conflated with asana, which is a huge misapprehension,” says Richard Rosen, director of the Piedmont Yoga Studio in Oakland, California. As integral to yoga as exercises on the mat are, they are only part of the picture, in the same way that bridges are more than the sum of their piers, beams, and decks. Focusing on exercise and competition is mistaking the nuts and bolts of the craft for the art of the craft.

Competition is ultimately driven by the ego and is based on a zero-sum game of loss and gain. Competitors seek to satisfy their own personal ends. Applause and prizes animate the fear and desire of the ego in accomplishment. Winners and losers are inevitably segregated, so that winners are enthroned and losers forgotten. Who remembers last year’s second-place finisher?

Nobody does, because losers don’t get the headlines.

Contests are defined from without, not from within, since referees, audiences, and media analysts are what validate the competitors, not their own efforts. Vince Lombardi, the legendary NFL coach who is a symbol of single-minded determination to win at all costs, once said, “If winning isn’t everything, why do they keep score?”

The answer might be because without a scoreboard the contest would be meaningless.

Prime time competitors often say they are their own competition, their own worst enemy. My biggest competition is myself. I’m always trying to top myself. I don’t worry about what other people are doing. I’m not in competition with them. I’m only in competition with me.

Competing with yourself is a slippery game when the ego competes against the sub-conscious even though the ego rarely knows what the sub-conscious is up to. Not only that, they are not best friends. It’s not necessarily in our own best interest to compete with our past, in the belief that progress is the measure of all things, and the asana we do today must necessarily be better than yesterday’s pose.

One Sunday afternoon, at the end of a crowded community class, a tall lanky older man on the mat next to me said, “I shouldn’t have even come today. I couldn’t do anything right.” He hadn’t fallen out of any balancing poses on top of me, but when I pointed that out to him, he said, “I’ll do better next time.”

The next time I saw him at the yoga studio his practice was constrained by a bad wing. “I hurt it here,” he said. “I think I was trying too hard.”

Self-consciousness and arbitrary reference to past standards compromises the here and now of yoga. The immediacy of the practice becomes a mishmash of then, now, and whenever.

Competition and progress take the man and woman out of himself and herself and out of the moment, positing a judge as the ultimate arbiter of their efforts. Even Rajashree Choudbury admits, “If you think you are competing against others, you won’t win.” Winning is freighted in terms of dollars and cents so that it makes commercial sense when applied to sports, but ultimately makes no sense when applied to the fabric of yoga practice.

“In the course of time asana or yoga postures gained more popularity in the physically-minded West, and the Vedantic aspects of the teachings fell to the sidelines,” David Frawley wrote in ‘Vedantic Meditation’.

Vedanta, or the philosophy of self-realization, underpins the concept of yoga as a spiritual system with a physical component, not a physical system with a spiritual component. Competition turns yoga on its head so that physical practice and fitness are conflated with yoga success, while spiritual discipline and self-realization are shunted to the sideline.

The prevailing modern view of yoga is that the means and end are the same. Yoga means exercise and exercise means yoga. Fitness is the means and fitness success is the goal. Articulated like that competition and tournaments make sense.

Most physical activities, such as throwing a ball, kicking a ball, or hitting a ball with a stick, can and probably will end up as grist for the mill. Most contemporary yoga flies in the face of its past, in which yoga exercise becomes both a means to an end and an end in itself.

While it is true practicing asana is practicing asana, moment to moment sweating on the mat, there’s no reason one’s sweat should just go down the drain. At the same time that you’re sweating up a storm in warrior pose, for example, you can be expanding into other aspects of yoga life and death, such as breath control, symmetry, and stillness. In this more traditional way of practice, competition is beside the point. In modern terms competition posits the ‘Other’ as superior to the self. In pre-modern practice the ‘Self’ is the center, not some imaginary logos.

Hatha Yoga, which is the physical branch of Raja Yoga – itself the meditative school of yoga – is simply a system of bodily postures meant to teach stillness under duress, breath control, and ultimately the strength to sit in meditation without squirming. As such it is folded into the other three traditional schools, which have to do with karma, self-enquiry, and surrender to the divine.

“The main objective of hatha yoga is to create an absolute balance of the interacting activities and processes of the physical body, mind, and energy. If hatha yoga is not used for this purpose, its true objective is lost,” says Swami Satyananda Saraswati, the founder of the Bihar School of Yoga. Separating asana from the rest of yoga, and mixing it up with competition as though it were a circus act or a sport, is to confuse the part with the whole, or the steps on the path with the pilgrimage.

“Yoga is a mess in the west. And you can quote me on that,” said Georg Feuerstein, a yoga scholar and teacher. “People shortchange themselves when they strip yoga of its spiritual side.”

The stuff of body sense mind are the means to achieve union with knowledge, whether it is self-knowledge or knowledge of a universal spirit. Commingling asana and competition trivializes yoga practice. When the breath, mind, and spirit are separated from the body, the gaze of the man or woman on the mat is lowered to the near horizon.

Sometimes during especially difficult asana classes at her Inner Bliss studio Tammy Lyons reminds everyone, “It’s a practice, not a performance. Connect through the breath, and remember you are more than your accomplishments.”

Handstand may be athletic and acrobatic, but yoga is not athletics in search of handstand. Although yoga studios are being redefined as gyms in our performance-driven world, it is a problematic change. Rather than reducing yoga to Hobbesian metaphysics, it might be better to restructure it back into its traditional guise as a spiritual practice with a physical component.

Yoga postures are ultimately meant to lead to the breath, which hopefully leads to Kundalini, and maybe somewhere down the long bendy road to a last second slam dunk on the podium of Samadhi, where there are no cash prizes no first place last place no jazzed up trophies no trips to the Dream of Winner Takes All.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”