By Ed Staskus

Erin McQueen isn’t a blonde, doesn’t often wear pearls carry a silk hand fan or suit up in gilded dresses with bows at the breast and puffed sleeves, and rarely looks perplexed. She does, however, speak with an English accent, which comes in handy when you’re a blonde sporting a string of pearls in a posh dress in the Restoration-era play “The Man of Mode.”

Staged by the Fountain School of Performing Arts at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the comedy by George Etherege is about a notorious man-about-town trying to slip-slide out of his love affairs and win over the young spunky seemingly virtuous heiress Harriet.

The play hit the bright lights way back when at just the right time. William Shakespeare had died 60 years earlier. The screws tightened by the Puritans had been recently loosened and women were finally being allowed to play female roles on stage.

There’s nothing like a gal in a gal’s role, rather than some scruffy cross-dresser.

“The make up and costumes are totally different from any other show we’ve done,” said Erin, then in her final year at the school. “Having the period costumes is really exciting. It’s a total transformation. The play truly is an authentic glimpse inside the intricate dating scene of 1676.”

Although she paced her prowling at a good trot, cast arched looks in the stagecraft of 17thcentury love stories, and had at it with barbed one-liners, like everyone else in a play that is all innuendo and intrigue, unlike everyone else in the play her English accent was neither feigned nor all wrong.

Even though she graduated from high school in Canada, spent four years at Dalhousie University, earning a Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Theatre, lives in Victoria on the south shore of Prince Edward Island, and her father is Canadian, she isn’t, not entirely Canadian, not exactly.

Erin McQueen is British, born and bred in Bristol.

“It’s right on the border with Wales,” said Erin.

Iron Age hill forts and remnants of Roman villas dot the southwestern British landscape. In the 11thcentury the town was known as Brycgstow, easier to pronounce then than it is now. The port was the starting point for many of the voyages of discovery to the New World in the 15thcentury. Today the modern economy of the city is built on aerospace, electronics, and creative media.

Unlike most cities, it has its own money, the Bristol pound, which is pegged to the Pound sterling. “Our town, our money,” is what they say in Bristol. Since money is a matter of belief, it’s best to believe in what you’ve got.

“There are a lot of art festivals,” said Erin.

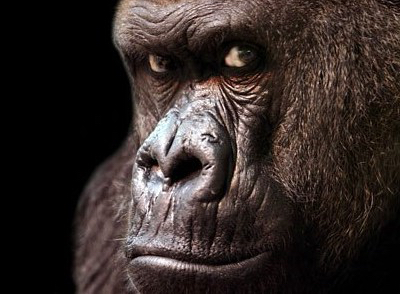

“They do a scavenger hunt every summer with ceramic animals. They started with gorillas, giving giant ceramic gorillas to artists, who painted them, and businesses sponsored them in their shops and on sidewalks, where you had to find them. They have a theatre festival, too, but that only started when we left.”

She was 16-years-old.

“The first time we came to Canada we went to see Halifax, where my father was born. It also happened to be the 150thanniversary of ‘Anne of Green Gables.’ My sister Caitlin was a massive fan. My parents finally said, ‘OK, we are in Halifax anyway, we’ll just pop over to Prince Edward Island.’”

She was 11-years-old.

“We did the tour, all the Anne of Green Gables things,” said Caitlin McQueen. They stayed in Victoria, a small village of maybe one hundred residents near the Westmoreland River. It is much, much smaller than Bristol, which is the 8thlargest urban area in England, home to nearly a million.

”I remember saying to Erin, I know I’ve never been here before, but I feel like I am coming home. I feel like I am supposed to be here. It is a dream come true.”

“I don’t really know what happened after that,” said Erin, “but the next year and for a couple of years after, we came back, and we always ended up in Victoria.”

While on a return trip, Andy and Tania McQueen, Erin and Caitlin’s parents, bought a lot overlooking the village harbor. In 2012 the family immigrated to Canada. They commissioned a house to be built, to be completed for occupancy the following spring. That winter was the winter they almost went back to the UK, back to England, back to Bristol.

“We spent a year living in Hampton, just up the road, in a rented house that had no central heating,” said Erin. ”I’m honestly surprised we didn’t move home that winter, because it was horrible.”

The winter months on PEI can be cold, temperatures averaging below zero in January and February. There are many storms, veering from freezing cold rain to freezing cold blizzards. The February 2013 North American blizzard started in the Northern Plains of the United States. By the third day of its arrival in the Maritimes there was heavy snowfall, wind gusts were hitting 100 MPH, more than a thousand flights had been cancelled across eastern Canada, and all Marine Atlantic ferries were suspended.

There was nowhere to go, anyway. There are few things as democratic as a snowstorm. It’s the same everyone everywhere.

“I feel like many people on this island have done that, lived without central heating, but British people aren’t cut out for Canadian winters in unheated houses. I had a comforter on my bed and many, many blankets. I often wore two pairs of pajamas.”

The McQueen family stuck it out.

“The main reason we didn’t move back to England was probably pride,” said Erin. “Obviously, you can’t move back after five months because your whole family back home would be saying, ‘Oh, so that didn’t go well?’”

The McQueen family cats stuck it out, too.

“They are rescue cats, Callie and Zebedee, and we got their vaccination papers together, and applied for pet passports. My uncle said, ‘Why don’t you just get new cats?’”

“You did not just say that!” said Tania McQueen. “They’re part of the family.”

“Let me tell you, though, cats do not like emigrating,” said Erin. “It traumatized them a little. The only other animals on the plane the eight-hour flight were two dogs, a little thing that barked all the time, and a big, quiet German shepherd. We’re still making up for it six years later.”

The cats slept in front of the fireplace in the living room in the rented house from morning to every next morning from the beginning to the end of winter. Unlike the upstairs rooms, there were no doors downstairs shutting the living room off from the kitchen and two back rooms. They made doors out of blankets to conserve the heat in the living room. The cat litter box was in one of the small rooms, behind a blanket door.

“They would wait quite a long time, and then dart behind the blanket, and as soon as they were done, run back in to the fireplace.”

The school buses stayed the course. Erin enrolled at Bluefield High School to complete her last two years. The family had waited leaving England until she finished her first set of high school exams there.

“It’s a big thing,” she said. “Everyone in the country takes the same exams. You study for them for two years. It’s what you’re working up to that whole time.”

Bluefield High School is in the small town of Hampshire. A $2 million dollar addition in 2000 enlarged and modernized the school, which as well as secondary education trains in carpentry, welding, and applied technology. All of its classrooms feature SmartBoards and there are two computer labs. The sports teams from badminton to hockey are all called the Bluefield Bobcats.

The school is thirteen miles and 90 minutes from Victoria.

“The bus went everywhere, so by the time I got there I didn’t really know where I was, because we had gone all over the island. My first day we did orienteering, even though the school is just surrounded by forest and potato fields. It wasn’t like you ever came across any houses. It was very different from Bristol.”

Her plan had been to study fashion design and costume, but her plans changed. “They didn’t have any sewing or couture classes. They did have drama, so I thought, I guess drama is where my theatrical tendencies are going to have to go.”

After graduation she enrolled at Dalhousie University, majoring in anthropology, keeping acting in the back of her mind. “I took acting as an elective and later auditioned for the program. If I get in, I’ll think about it, I thought. I didn’t think I actually would. And then I did.”

In order to find the unexpected it’s best to expect it. You can’t plan for it, but it’s what often changes your life. ”All creative people want to do the unexpected,” said Hedy Lamarr, the glamorous Hollywood starlet and designer of a patented frequency-hopping radio guidance system for torpedoes. Even though she once said, “Any girl can be glamorous, all you have to do is stand still and look stupid,” her smart invention was the precursor to GPS, secure WiFi, and Bluetooth technology.

“My sister is the anthropologist, no acting, although she’s fascinated by actors,” said Erin. “She thinks she might do a research project about them one day. Actors never know what the future holds. They’re rarely employed for a long time, always on the way to their next role. It’s living on the edge. It’s the idea that you could love doing something so much that you choose that over stability or financial security.

“That’s what I want to do.”

It’s taking the show on the road. “I’m just going to start auditioning in Halifax. There are so many small weird theatre spaces. I’m thinking of potentially writing a fringe play.” She has no plans of pursuing the discipline of anthropology.

Her four years studying the arts and sciences of theater at Dalhousie University were matched by four summers working in theater in her newly adopted hometown.

“My parents saw there was a job at the Victoria Playhouse. I needed to work in the village. It was the perfect job, since although I do now drive, I couldn’t drive at the time. I could meet people in the industry, too.”

The Victoria Playhouse, in the middle of town, in what used to be the Victoria Hall, seats about 150, and has been producing and presenting live theater and performance events for thirty-seven seasons. In 2007 it was designated a ‘Historic Place’ on the Canadian Register of Historic Places. History gets made every summer seven days a week on its stage.

She worked the refreshment stand her first two summers.

“I don’t do that so much anymore,” she said last summer. “You could say I’ve moved up.”

She worked part-time in the box office, then went full-time, and worked front of the house. Odd jobs became must-do jobs. “I helped one of the actors run their lines, and then I did that a couple more times.” When the stage manager was conscripted to do lighting cues, she went backstage. “I gave the actors their places, which was exciting. I’ll do whatever it takes to make sure the show goes on.”

Sometimes the lighting cues are on the sturm und drang side of the curtain, occasioning careful calculation. Higher than normal water temperatures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence can and do morph into massive thunderstorms, roiling the island. It is batten down the hatches and check the flashlights.

“In villages like this, in bad thunderstorms, power goes out,” said Erin. “The doors are going to open in twenty minutes, the power keeps flickering off and on, and the management has to make a call about whether you think you can make it through the show.”

She became one of the emcees at the front of the stage, pointing out the exits, encouraging donations to the theater, and introducing the play. After the show was over was her favorite time. “It might sound corny, but at the end of the show, when we get to open the curtain and the applause, and afterwards the actors are happy, a kind of high, even with small crowds, that they brought a story to life and created some magic for the audience.”

After her employment contract at the Victoria Playhouse expired at the end of October, she moved back to Halifax, where she went to university, and where there is a red-blooded theatre scene. It is zesty and diverse, ranging from Zuppa Theatre, whose performances defy categorization, to the Neptune Theatre, whose performances outpace categorization.

“Some of the actors who worked at the Playhouse live in Halifax, so that’s quite cool,” she said. “They came to my shows at Dalhousie and I went to their shows.

“Acting, that’s my plan.”

If in the event a professional acting career doesn’t pan out, she is determined to keep her foot on the boards, front back or in the wings. ”If I wasn’t an actor, I’d be a secret agent,” said Thornton Wilder. Erin’s secret is all parts of the theater business interest her, from acting to directing to writing to the nuts and bolts.

“If I’m not acting, I will definitely be doing something in theatre. It’s plow ahead.”

It’s keeping your hand on the gospel plow.

“A part of me is intrigued by stage management,” she said. “Stage managers are another level of human being. They’re like super people with super powers. They’re the people you go to if you have any issues, personal, professional, or logistical. One of my stage managers at Dalhousie had a locker full of extra clothes and every kind of medicine you could imagine. They are prepared for anything.”

A career in the arts often means being a jack-of-all-trades.

“I am very into doing whatever I can,” said Erin.

If you want to accomplish anything something everything, you have to be willing to do whatever it takes, maybe not blood, but certainly sweat, and probably a locker loaded for bear, to make it work, to make it happen.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”