By Ed Staskus

As many times as I met Matt X. Sysack was as many times I didn’t meet his father Russell X. Sysack. Matt was my brother-in-law’s best friend. They met during their freshman year at St Ignatius High School on Cleveland’s near west side. My wife and I and my brother-in-law and Matt often went out together to weekend breakfasts, to shows, and to haunted houses. We went to honky-tonks to listen to the rock and roll band my brother-in-law played lead guitar for. After the two young men finished college and started on career tracks, they decided to not be too serious about life, at least not just yet. They decided to be fun guys while there was still some fun to be had.

Neither of them lived on their own at the time. When they bought motorcycles they kept them in our garage. When they bought a Jet Ski together they kept it and its trailer in our garage. They launched the Jet Ski from Eddy’s Boat Harbor in the Rocky River Metropark a couple of minutes from our garage. We called the Metropark by its local name, which was the Valley. There was a bait shop at Eddy’s that sold ice cream. I had a cone one day while I watched the Sunday sailors launch their craft.

It was only a couple thousand feet down the river to Lake Erie and fun riding the waves, except when they ran out of gas a half-mile out on the lake. When they did they discovered there wasn’t a paddle on board. A Good Samaritan in a power boat threw them a towline and got them safely to shore. It wasn’t long after that before they stopped cranking the throttle on the craft’s impeller.

Both Matt and my brother-in-law eventually sold their motorcycles and their Jet Ski and mothballed fun and games for the foreseeable future. “Hustle it up” is what they said. They put their noses to the grindstone. Matt’s father, Russell, always had his nose to the grindstone. He was a hard-working man with a family to support. At the same time, he never put his irreverent sense of fun away. He wasn’t going over the hill anytime soon. He knew over the hill meant picking up speed on the other side.

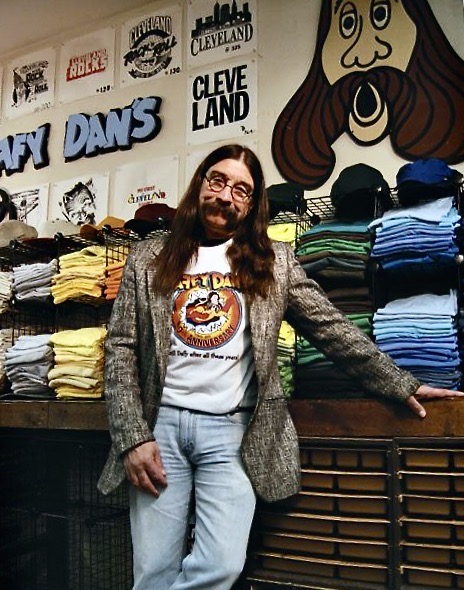

Russell X. Sysack was born in Cleveland and went to John Carroll University, a Jesuit school in University Hts. After graduation he became co-owner and manager of the family business, Sysack Sign Co., in Old Brooklyn on Cleveland’s near west side. He sported a Waylon Jennings beard and overalls at work. The work he did was hand-painted signs, from small displays to big-size displays. When Russell’s father Harry X., who opened the business in 1940, punched the time clock for the last time, Russell took over. Over the years the Sysack Sign Co. gave the high life to innumerable storefronts.

Russell mixed business with pleasure. He was a libertarian and provocateur, more in your face than subtle. He was outspoken. He was subtle as a sledgehammer. His signs were everywhere around northeastern Ohio. In the meantime, he had his own op-ed billboard at the front of his sign shop. It was across the street from a public library. His work for others expressed what their goods and services were about. His personal billboard was where he expressed himself. It was where he expressed himself In 2002 when he compared Martin Luther King, Jr. to Osama bin Laden. The comparison let the terrorist play his own tune; it insulted Martin Luther King, Jr. The billboard was set on fire one night. The Cleveland Police wrote up an incident report and filed it. Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones led a protest march.

“Mr. Sysack has said that over the years he’s been sued and received bomb threats because of his signs,” the Sun Press reported. Russell explained his resilience by saying “I take the right of free speech very seriously.” Stephanie Tubbs Jones wasn’t having any of it. “The right to free speech is limited,” she said. Nobody is allowed to falsely shout “fire” in a crowded theater, she added. The First Amendment doesn’t protect words “that incite people to violence.”

The community was divided. “Those signs were the highlight of my day when I was stuck in traffic on W. 25thSt.,” Anna Namoose said. For some, his words were signposts. “I love his truthfulness,” Dale Bush said. “Sorry if the truth hurts.” Some were perplexed. “Every time I see his signs I’m struck with the same thought,” ‘Silent Dot’ said. “Sir, what do you think happens next? Do you think that someone driving by will stop and read your sign and go ‘Holy cow!’ this guy with the sign is a genius. I’m going to drive to the State House to speak my mind right now!” Others were outraged. “I hope your racist business closes,” Monica Green said. Some took an art school approach. “This is a special kind of batshit insane outsider art,” Adam Ohio said.

One man, at least, took a philosophical approach. “Russell Sysack has been in our consciousness since the ’80s,” Tim Ferris said. “He really got going on issues in the ’90s when Mayor Mike White began compromising the public interest. He might be extreme, but he’s necessary. He forces us to think back towards a middle position. By temperament, perhaps by training, he’s a cartoonist, and it’s his purpose to distort and amplify so as to reveal or enlighten. We shouldn’t take cartoons too literally. Those who do, do so with the intent of silencing him. We also need to realize that we can’t look for good taste when it comes to addressing outrageous or extreme abuses. He speaks to big problems, and he uses strong talk.”

He posted his strong talk on his personal billboard year after year and appeared regularly on local mouth-foam talk radio. His targets were Martin Luther King, Jr., the city’s African American mayors, and Black History Month. Politicians weren’t his favorite creatures. If they were Democrats, so much the worse for them. He celebrated Edward Kennedy’s death on his personal billboard, despite the Massachusetts senator being still very much alive. Public education and the Catholic church were targets of his ire. Anything new-fashioned was fair game. He compared environmentalists to Nazis. “The only way to make the earth green and stop global warming is for all humans to die” was what one sign said.

The near west side sign man worked in the “Simon Sez” tradition even though he worked outside of the tradition. Buddy Simon was the sign man on the near east side of town. He hung a “Simon Sez” sign outside his Carnegie Ave. shop every week for more than 30 years. They were usually wry and funny observations about the way we live today. He kept his nose out of race, religion, and politics. He stayed on the Mr. Rogers side of the street. Nobody ever set any of his signs on fire.

Russell X. Sysack was more of a soapbox man than Buddy Simon, although his soapboxing was more diatribe than not. He was a worried man singing a worried song. He was worried about how the present was going to affect the future. He stood by Abraham Lincoln, who said, “You cannot escape the responsibility of tomorrow by evading it today.”

Splashing his op-ed sign on the street where everybody could see it, he wasn’t holding back. He said he standing up for the taxpayer and the small businessman. He told anybody who would listen he was a defender of the American way of life, by which he meant capitalism. He said he was a patriot. He was met with threats, vandalism, and litigation. There were widespread complaints of racism. “I’m just expressing my opinion,” he told the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the city’s morning newspaper.

In this corner, still undefeated, it was Russell X. Sysack’s long-held opinions and beliefs. He didn’t need a referee. He gave as good as he got, even though his facts weren’t always reliable. Free speech advocates argued he was entitled to his own opinion. His detractors said he wasn’t entitled to his own facts. “Opinion has caused more trouble on this earth than plagues and earthquakes,” said the French Enlightenment writer Voltaire. The trouble with opinion is, more often than not, the fewer the facts the stronger the opinion. The White House under the thumb of a latter-day rabblerouser testifies to the trouble that can ensue.

In retirement, Russell X. Sysack became a crossing guard for the Parma schools, working the streets in his neighborhood. He helped children cross the street safely. His presence made parents feel easy in their minds about their children walking to school. He reminded drivers in no uncertain terms of the presence of underage pedestrians. Nobody was ever run down on his watch. Pity the fool who tried to barrel down the road at 21 MPH.

After he stepped aside from the sign company his sister Nancy took over the business, She lived in a house attached to the back of the sign shop. She was a chip off the old block. She kept up the family practice of posting the Sysack point of view on the op-ed billboard in front of their building. One of them had to do with migrants.

“The head of DHS is a Communist & a Treasonist. On May 11th he will open the southern border. No illegal will be refused entry. US troops will transport them to every city in the US. They went to Panama to organize this invasion using NGO’s & the cartels with taxpayer money. 8 million will enter this country by year’s end from 150 countries. China has warships in the Bahamas. The plan is to overwhelm our system, crash our economy, and create a national emergency. There will be a fundamental change of our country into Communism. What are u going to do about this invasion?”

As it happened, nobody did anything because there were no Chinese warships in the Bahamas and no US troops were escorting anybody anywhere. The secret messages and conspiracies went up in smoke. The invasion was a nonstarter. Nancy went back to the drawing board.

Her “Ugly Ugly Ugly” sign ruffled more than one feather in 2017. It featured a woman’s wide open Rolling Stones-like mouth outlined in bright red lipstick. It said “All Women Are Beautiful Until They Open Their Mouth” and listed some women the sign maker considered loudmouths. It was in the tradition of bad taste making more millionaires than good taste.

“The sign suggests women only have, or their mouths in particular, only have one purpose, and I find that greatly offensive,” said Christopher Demchak, one of the organizers of a demonstration. “Particularly in this political climate and particularly when young children and families are driving by.” The protestors were hoping a demonstration would influence the sign company to stop posting offensive content. They didn’t know who they were going up against.

“We don’t want to cover up this message and stop somebody’s voice, since this was a woman who put this message out, interestingly enough,” said Christen DuVernay, the other organizer. “But, we do want to provide alternative messages for young girls in the community to say ‘your voice does matter.'”

President Barack Obama became the dartboard for Nancy’s darts when he was elected. “Now that red-necked and facist America elected Obama on a campaign of change, will blacks show their gratitude & change? Hell no. Will Jesse Jackson & Rev. Al stop being racists? Hell no. Will blacks stop using slavery as an excuse? Hell no.”

When Russell invoked the First Amendment one of the things he meant was, if you can guarantee never offending anybody, you don’t need the amendment. It doesn’t guarantee you the right to be heard, though. Nobody has to read or listen to anything you have to say. All media has an on-off switch, even billboards, Look the other way if it rubs you the wrong way. You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the message blows.

Russell X. Sysack died in 2009. He was in his mid-60s. He had run whatever race he was running. Wherever he has ended up, with the stand-up saints or the fallen angels, he is undoubtedly making his idiosyncratic voice heard, loud and clear.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Late summer, New York City, 1956. The Mob on the make. The streets full of menace. President Eisenhower on his way to Brooklyn for the opening game of the World Series. A killer waits in the wings. A private eye working out of Hell’s Kitchen scares up the shadows.

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication