By Ed Staskus

It was a hot and humid day. The city as far as the eye could see smelled bad. The sky was dotted with dull clouds. The old hot dog Ezra Aaronson had wolfed down for breakfast was giving his stomach trouble. On top of that, the bunion topping his left big toe was throbbing in the new shoes he had forgotten to stretch beforehand.

It was a bad day to be having a bad day but that’s what it was turning into. Now the other penny was dropping. One of them was big and looked mean. The other one was smaller and looked meaner. He kept his eyes on the big bad penny. He kept his sense of preservation on the small bad penny. Ezra was sure nobody else was behind him to trip him up but running fast and far was going to be a problem with his bunion. He kept his hands at his sides, his right hand balled into a fist.

“You can forget about that roll of pennies in your hand,” said the small bad man next to Big Paulie.

Luca Gravano was Big Paulie. He wasn’t tall as in tall. Instead, he was all around big, a dark suit, dark tie, and a white shirt. His face was sweaty and pockmarked. He wore browline glasses. The lenses looked like they were smeared with a thin film of Vaseline. His brown eyes were slippery behind the glasses. It was no picnic trying to focus on them. His shoes were spit shined. He stank of five-and-ten store cologne.

“They’re not Lincoln’s,” Ezra said. “They’re Jefferson’s.” He could use a lucky penny. A rolled-up copy of the Declaration of Independence wasn’t going to get it done. Maybe Honest Abe might come around the corner with the axe he used to spilt logs back in the day. Maybe he could help. Ezra wasn’t going to hold his breath.

“OK, let’s cut the crap,” Big Paulie said. “We ain’t going to get up to anything here, broad daylight, all these guys around, left and right.” He waved a beefy hand over his shoulder. “We just wanna know what it is you wanna know.”

Ezra looked past the big man. On the finger pier side of where he was a freighter lay at rest Hemp slings were lifting swaying pallets off the boat. In the distance he could see the Statue of Liberty. On the dockside was a two-story brick building. A loose group of longshoremen was coming their way, baling hooks swinging on their belts. They would be DD&B if anything did get up to something.

“I don’t know nothing about it,” they would all say, deaf, dumb, and blind after it was all said and done. But they might be the smoke screen Ezra needed to be on his way. He could see plainly enough he needed a way out.

“I’m trying to get a line on Tommy Dunn,” Ezra lied. He never told anybody what he was really working on. He wasn’t working on these two goons. Why were they getting in his face?

“Never heard of him,” Big Paulie’s small man said.

“Fair enough,” Ezra said.

“You a private dick?” Big Paulie asked.

“Yeah.”

“Who you work for?” the small man asked. He had yellow fingernails and sharp front teeth. He wore a felt pork pie hat. He was in shirtsleeves. There were spots of spaghetti sauce on the pocket on the front of his shirt.

“Ace Detectives,” Ezra lied again.

“OK, I’ve heard of them.”

“Best you beat feet,” Big Paulie said, staring at Ezra. It was a fixed look. “Tough Tony don’t like nobody nosing around for no good reason, know what I mean?”

“I take your meaning,” Ezra said.

“Don’t forget what I said here today.”

Ezra took a step back, smiling like warm milk, and walked away in stride with the group of longshoremen going his way. He hated shucking and jiving, but he knew enough to hedge his bets. The rackets ran the shaping-up, the loading, and the quickie strikes. They hired you for the day if you were willing to kick back part of your day’s pay. At the shape-up you let them know you were willing to play ball by putting a toothpick behind your ear or wearing a red scarf or whatever it was they wanted to see. If they liked you they saw it.

They controlled the cargo theft, the back-door money stevedores paid to keep the peace, and the shylocking from one end of Red Hook to the other end. They didn’t steal everything, although they tried. The unions were hoodlums. The businessmen were hoodlums. The pols were hoodlums. The whole business was crooked left and right and down the middle.

The Waterfront Commission hadn’t gotten much done since they got started, even though the State of New York and the Congress of the United States had gotten on board in thought and word. It was taking time finding the gang plank leading to deeds. It was just two-some years ago on Christmas week when a new union full of do-gooder ideas butted heads with the ILA. Tough Tony flooded the streets with the faithful. It took hundreds of club-swinging policemen from four boroughs to break up the riot at the Port of New York. Staten Island sat the melee out. In the end, only a dozen men were sent to Riker’s Island while emergency rooms filled up and mob rule continued to rule the roost on the docks.

Ezra put the roll of nickels back in his pants pocket. He walked the length of the wire fence to the gate. Through the gate he turned his back on the Buttermilk Channel. He couldn’t settle himself down, a sinking feeling in his gut making him feel queasy. Red Hook was surrounded by water on three sides. A longshoreman leaning on a shadow stared at him. He crossed the street into the neighborhood. The houses, six-story brick apartment buildings, were less than twenty years old, but they had already gone seedy.

“I need a drink bad,” he said to himself.

Most days Ezra ran on caffeine and nicotine. Most nights he ran on alcohol and nicotine. Even though it was only late morning, today wasn’t most days. He found a bar and grill at the corner of Court Street and Hamilton Avenue. Sitting down at the bar he ordered a shot and a chaser. He looked up at the bartender. The man was broad and wearing a bow tie. He looked like a king-size mattress wearing a bow tie.

“What have you got on tap?” Ezra asked.

“Ballantine, Schlitz, Rheingold.”

Two longshoremen sat on stools a couple of stools away. Bottles of beer, most of them empty, squatted in front of them. Neither man had a glass. They ate pickles from a jar. The TV on a shelf behind the bar was on, although the sound had been turned down to nothing. A beer commercial was running. It was a ticker tape parade through Times Square, but instead of war heroes or celebrities everybody in the parade was a bottle of Rheingold.

“Nobody knew what that was about,” said one of the longshoremen, pulling a pack of Lucky Strikes out of his shirt pocket. The bartender knew what they were talking about. Ezra didn’t have a clue.

“I got no trouble,” the other one said. “Me, I support my family. It’s good work, keeps me out of trouble. I got my old lady and three kids.”

“Nothing changes,” the Lucky Strike man said lighting his cigarette. “You just live every day as if it’s your last.”

“I’ll have that Rheingold now,” Ezra said after throwing his shot back, feeling it burn going down his throat. “Make sure the glass is as cold as can be.”

“Sure thing, bud,” the man mattress said.

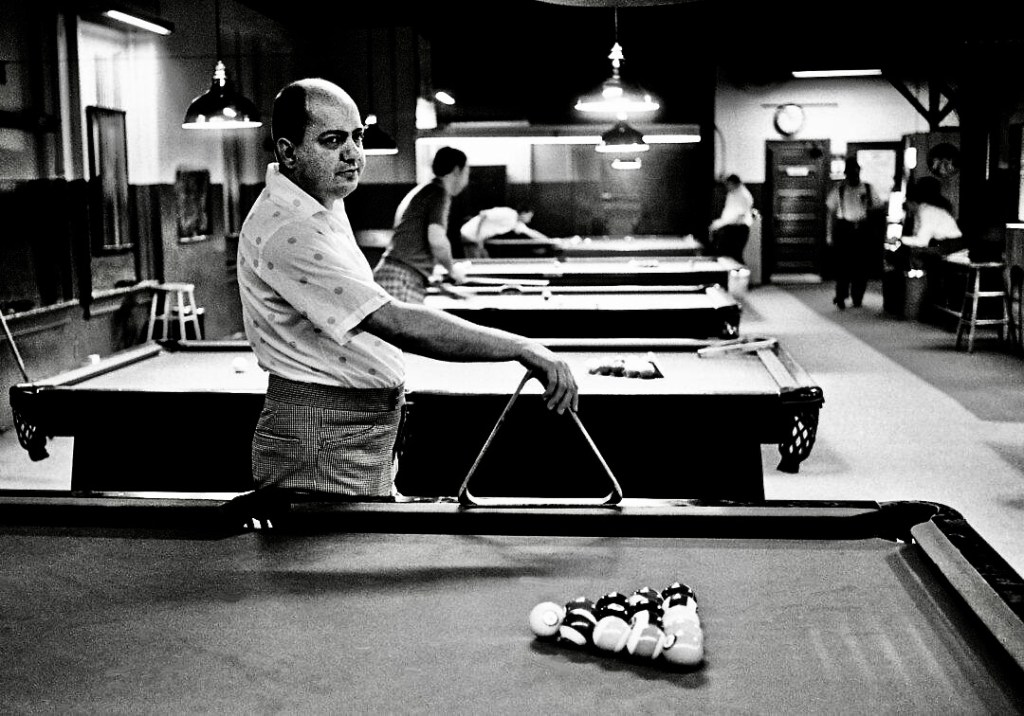

Photograph by Sam Falk.

Excerpted from the crime novel “Cross Walk.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“Captures the vibe of mid-century NYC, from stickball in the streets to the Mob on the make.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn. New York City, 1956. President Eisenhower on his way to the opening game of the World Series. A hit man waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication