By Ed Staskus

I would trade any day in the real world for a minute at summer camp.

Those two weeks are what I wait for all year. It’s hard to believe, but my best friends and I and everyone who knows us best have been going to camp for half our lives, just after I turned seven. Since then I have gone every summer. The first day of camp is better than the rest of time.

I used to go to Camp Katahdin with my dad when he first started taking Katie and Sylvia. I went along to keep him company on the drive, because my mom wouldn’t go, and the girls were just girls. After dropping their duffels and backpacks off and getting them signed in, we would walk around the campground, to where it is fenced in along the lakeside, although most of the fence is now rusting and falling down.

My dad and his sister went to the camp in the 1960s, before there were real highways and it took forever. They rode in granddad’s Chevy Impala, a green woody wagon that was twice as big and long as the Hyundai dad drives to work. The third row seat faced backwards. That is where he and his sister sat, what they called the way-back seat, playing the license plate game and category abc’s.

They slept in Canadian Army tents at the camp in those days, not the A-frame cabins we sleep in now. They had bonfires and sing-a-longs every night and ate peanut butter and grape jelly on Wonder Bread. “Some days we had sandwiches three times a day if there wasn’t anything else,” my dad says.

“There was so much wood we had bonfires every night, as big as a house burning down. Not like now, when you have to drive to the convenience store and buy it,” he said, pushing the wrapped-up firewood packages with his foot. We only have bonfires on weekends and they are more the size of flashlights than three-alarm fires.

“One of our camp commanders back then had been in the French Foreign Legion. He wore a black beret and a small hand axe on his belt. He just picked wood up in the forest. We always had more than we wanted, the woodpile was so high.”

When it was late afternoon and the girls were finished at the orientation we would leave for the ride home, driving all night, listening to talk shows and baseball games on AM radio, twisting the knob on the dashboard back and forth as the game or the talk show faded in and out. My dad likes talk shows so he only listens to AM radio.

I knew I wanted to go to summer camp the first time I saw it. Since the girls were already going I knew I probably would, too. I just had to wait to be at least seven-years-old. Every summer they told me how much fun it was to be at camp and not at home. That was the big thing, they always said, to be away, to be somewhere else for two weeks.

Summer camp is a different life than being at home. There are fewer adults than anywhere else and no parents. The counselors are almost like you. Some of them let you run amok and hope no one dies. All of your friends are together and there are even more of them than you have at home. Nobody yells at you for two weeks. The counselors scream if you do something really dumb, but you don’t get yelled at for just doing something wrong by mistake. Even when you do it’s all over in a few minutes, not like at home, where it never ends.

You can’t always go wherever you want, roam around the camp, or just run around in the forest, but you can be who you want to be almost all the time. When you’re at camp it’s like waking up on the roof. The nights are dark and everything smells damp, like a bottle of milk in the refrigerator. Although everyone is supposed to be in after lights out, and there’s a night guard, he isn’t able to watch all the cabins all of the time. In the forest in the middle of the night when it’s quiet it’s scary quiet, and the quieter you are, just breathing, everything’s a strange echo. Sometimes it’s so dark walking is like feeling your way with your hands, but you never lose your way.

The sky at summer camp is clean and windy, not stuffy and dead like at home. Some kids don’t shower when they’re there and that’s disgusting, but nobody cares too much about it. Once somebody’s parents wouldn’t let him in the car when they came to pick him up. ”No, go hose yourself off, and brush your teeth!” his mother yelled. The cabins are gnarly old, partly plywood and partly brown clapboard, and moldy in some spots. They never smell all good, even on sunny days. There is a beat-up screen and wood door in the front and a tilt window in the back, although most of the time the window won’t crank open.

But, it doesn’t matter. The camp is big and so are the lake, the dunes, and the woods. We hardly live in our cabins, anyway, only sleeping in them, unless it rains.

Camp Ketahdin is a long drive from Cleveland, to the northeast shore of Lake Michigan, on Little Traverse Bay. It’s past a town called Petoskey, which means ‘Where the light shines through the clouds’, hidden down a winding gravel lane from the main road. The boy’s cabins are on one side of the camp, the mess hall is in the middle, and on the backside of the drive-in and packed-dirt lot is the chapel. The girl’s cabins and nurse’s station are on the other side and the flagpoles and bonfire are down a sloped sandy hill from the hall. The lake is a one-mile walk from the sport’s field.

A year goes by and it’s like I never left. As soon as we get to camp we unload everything we’ve brought, our clothes, sleeping bags, and snacks. Everything we own has our initials on it written with a Sharpie. We find our cabins and claim our beds, and then your parents are gone before you know it. Sometimes I don’t even realize they’ve left. You see your friends again, your cabin mates and everyone you have ever camped with, and there are high-fives, knuckle-touches, and bro-hugs all around.

Everyone punches each other and laughs, “What’s up, dude.” We hang out, reunite with the girls, and get some overdue hugs from them. When everyone has gotten to the camp and all the parents are finally gone we have sandwiches in the dining hall. Father Elliott says a prayer for the kids and new campers, and afterwards the camp commander gives us a chalk talk about everything. He writes the rules in block letters on the blackboard.

Before nightfall we hike to the beach for our first look at it. We go to the lake every afternoon, unless the weather’s absolutely horrible. But, when the day’s cold and gusty it’s really the best time, because there are huge waves, the wind is blowing hard, and the surf is smashing you. When we come out for a break the counselors have a snack set up for us, and later we go back in the water a second time, or just lay around on our towels.

We have activities every night, like bonfires, mystery night, and sleep-outs under the stars. There are three dances, the big one on the last night of camp, which is the formal dance. Some nights we do things later than the kids, like the manhunt game, because they have to go to bed before us. They sleep in the long barracks, not the cabins like us, where they have their own sleep-in counselor.

The last couple of summers the kid’s barrack counselor has been an immigrant, who is tall and pretty, but has bad teeth, is very serious, and barely speaks English. She has twin girls who stay in her room. She sweeps the hallway with a broom for a long time after all the kids have gone to bed. Nobody ever thinks about sneaking out. Everybody knows what would happen, because she tells them all in her own way on the first day of camp.

As soon as we’re done with the night activities, but before going back to our cabins and staying up, or whatever we do, we gather in a circle and cross our arms with each other. A counselor says a prayer and everybody shouts good night. Then it’s a mad dash back to our cabins. We always flip our mattresses over to get the sand and wolf spiders out. The spiders aren’t poisonous, but they can be big as your hand, and they bite hard as if they had teeth.

One year we had bedbugs. We caught them with scotch tape and kept them in a glass jar. We tried to kill them with poison spray, because when they sucked your blood they left itchy clusters of bites on your skin, but the bugs didn’t seem to care. When the camp commander found out he hired a bedbug-sniffing dog. The next day everyone whose cabins had bugs put everything they had in plastic garbage bags and put them inside the cars at camp, in the hot sun, with the windows closed. All the bedbugs died.

In our cabins we talk, jump into the middle of things, and beat each other up. We plan different ways to kill people, have wrestling matches, and see who can burp and fart the loudest. Whenever anyone falls asleep they are fair game. My fourth-best friend Tomas is an open-mouth sleeper. One night we squirted minty toothpaste around his lips and watched bubbles form as he breathed. Another time we covered his face with lipstick and mascara. He didn’t like that, but later he thought it was funny. We don’t fight or talk the whole time, at least, not necessarily. We eat a boatload of candy, too.

The camp doesn’t let us bring our phones or tablets, or even video games, but everyone brings four or five pounds of candy. Some bring less, but some bring even more, which is ridiculous. One boy brought four cases of soda and a carton of family-size Lays Classic potato chips with him, and that was on top of the pickings at the camp store, where you get two treats every day. He is 14-years-old, like me, but built like a twig. He ate and drank everything he brought and didn’t share it with anybody.

We have a food-eating contest every summer after the Counselor Staff Show. The kids have to go to bed, but we stay up late to play the game. Whoever volunteers is blindfolded and has to eat whatever the counselors make. Everyone has to keep their hands behind their backs and lap it up with their mouth like a dog. Sometimes the other kids vomit, but I never throw up. Last year the counselors made bowls of Rice Krispies with ketchup, mustard, jelly, lots of salt, and it was mashed together like potatoes. It was horrible. Everyone cheers you on and you have to eat it all as fast as you can if you want to win.

Some nights if we have stayed up until dawn the night before we try to go to sleep a little earlier than usual, no later than two or three in the morning. We don’t keep track, but we have to get some sleep because the counselors wake us up at seven-thirty for calisthenics. They march us to the sports field and make us do jumping jacks, push-ups and crunches, and run the track. If they see you are tired and slacking they will make you do more.

We get up every morning to dance music, like Katy Perry or Duck Sauce, or whatever the counselors want, played loud on loudspeakers hidden in trees. Sometimes I don’t hear it because I’m sound asleep. The counselors carry water shooters. If they say you have twenty seconds to wake up, and you don’t jump right out of bed, they start squirting you. They shake your bed and jump on you, and scream “Wakey wakey campers!”

After exercise hour on the sport’s field we go back to our cabins, clean up, and then raise all the flags before breakfast. Sometimes we don’t clean up and instead fall back asleep in our cabins and then are late for the flag raising, which means humiliation. Whoever is late has to step out into the middle of everybody on the parade ground and do the chicken dance, or whatever dance they tell you to do.

All the boys on their side of the parade ground do the chop when that happens, swiveling their arms like tomahawks and chanting. Nobody knows what it means, but they all do it, and the girls stand there watching, and then they do their dumb dance, like cheerleaders, but they aren’t cheering for you. We have some pretty messed-up people at camp, but everybody gets their share.

Every cabin has to keep a diary for two weeks and we get graded on it every day. Whoever is the best writer wins Liberty Dollars. But, if you write something dumb, like “ugi, ugi, ugi” or anything that doesn’t make sense, you get a bad grade. The counselors tell us to be sincere. Matthew always makes up our diary because everyone else in our cabin is retarded. At the flag lowering one time, after Titus had written something stupid, we had to do the Rambo, running down the hill to the flagpoles with no shirts on and singing “cha, cha, cha” while everyone did the chop.

My friends and I are in cabin three, which is the smallest cabin of the nine boy’s cabins. There are eight of us and the only space we have to move around in is to walk back and forth to our beds. Matthew is my best friend and totally number one. He’s a little shorter than me, has dirty blond hair, and is stick slender. We like to relax, not get uptight, and soft chill at the end of the day. We have been rooming together for seven years and know each other best.

Logan is my second best friend. He is a tad taller, funny, and chunky. He chews green frog gummies and spits them out on the cabin floor. He likes to play paintball. I don’t paintball, but I think I’d be better, considering I’ve never done it. He’s strong, too, but not loud and belligerent. Once he punched someone who stomped on his bad toe. He has in-grown toenails. Logan was, like, “Dude!” and he pushed him, and then got punched in the stomach. Logan punched him back in the face, but without being mean. It was the Night of the Super Starz in the dining hall, we were just sitting there watching the show, and the rude boy started crying. He had a reddish bruise and a black eye at the end of the day.

There was a midnight mass afterwards, but Logan had to go back early and alone to our cabin, although all that happened the next day was they made him sweep the hall. That’s somebody’s job, anyway, so he just helped, but not too much.

After the morning activities we eat breakfast, and then clean up our areas. You don’t have to do it, but there is a cabin judging at the end of camp. We didn’t win last summer, but we didn’t come in last, either, which is a good thing, because then you would have to do something bad. We go to classes, sometimes, or you can say you aren’t feeling good, and then we have lunch, and later go to the beach. After dinner we lower the flags, there’s an evening program, and then we go back to our cabins and get naked, at least some of us. I don’t know why we do that, exactly.

We talk about movies, television shows, and our favorites on YouTube. We talk about girls, some of them more than others, and we talk about video games, even though we don’t have any at camp. It’s never been allowed. The one of us in our cabin who doesn’t talk much is Titus. He just sits in his corner all secluded, but he does play some games, so I talk to him about that, sometimes.

I used to play WoW, but I got addicted to it and didn’t like that. Call of Duty is my game now, except I don’t play it on my Xbox anymore, only on my computer. I love it when they say, “In war there is no prize for the runner-up.” I’m not sure what games Titus plays.

Nobody knows what is wrong with Titus. We love Titus, but he’s quiet. He doesn’t do anything, which is the problem. At night when we’re sitting in our cabin talking, he’ll start crying. He’ll just cry on his bed, and when we ask him what’s wrong, he says, “I don’t know.” We don’t ignore him and we never do anything to him. We punch him every once in awhile, but not hard. Mostly when he’s looking, but sometimes when he isn’t looking. He gets pinkeye every year. We don’t make fun of him, though. But then he got double pinkeye

We were all, like, “God damn it, Titus.”

Everybody made fun of him as a joke, and then he cried, but not because of that, just because he’s Titus. Every year he sleeps in the corner by the door. That’s the problem, he doesn’t know. He is one sad, sad child.

We stage our wrestling matches in cabin two, which is the oldest boy’s cabin. It’s the coolest cabin, too, and the biggest. What we do is take our shirts off and duct tape a sleeping bag onto the wood floor. There is no punching allowed, no hammer blows, or anything like that, but you can kick and throw each other on the ground. We aren’t supposed to fight, because the camp commanders don’t like it, but everybody wrestles and gets bruised, and crap.

One night we had wrestle mania. The winner is the last man standing. Mason and Chase, two boys from cabin five where they’re younger, were locked together when Chase grabbed Mason’s head and flipped him over. Mason slammed hard into a bed and got knocked out. We let him lay there, but when he didn’t wake up for twenty seconds we threw dirt on him. He was fine after that. The next day we were walking to the beach and Mason jumped on Chase’s back for no reason and almost cracked it. But, they didn’t punch each other, or anything like that. They’re both hardcore kids, everybody knows that, but not haters. Besides, the counselors were watching, and that would have been trouble.

Liam sleeps in the other corner opposite Titus by the door. He’s a serious douche bag. He thinks he can play guitar, but all he does is play the same part of Stairway to Heaven over and over. Who needs that? We are always yelling “Shut up!” and then we broke his guitar, but it was a piece of junk, anyway.

We broke the brand new fan his parents got him, too. Logan was angry, his toes hurt that day, and he started hitting it with a comb. We took the fan behind our cabin and beat it with a bat. It was hanging on rags when we were done. The spiny part was smashed, giant chunks were missing, and we just kept beating it. We beat it with a hockey stick and threw bottles of water at it. I mean, we did everything to it.

He wasn’t too happy about it, but he deserved it.

When his parents came mid-week they asked him what happened. He told them we did it, but not surprising to us, they didn’t believe him. After that he tipped a Diet Coke over on my bed in spite, so I poured the rest of it on his bed, and he pushed me, and I punched him back, and then he punched me, and I finally punched him in the jaw, but not crazy hard, and he stopped.

He thinks he is swagged, but since he is Liam, there is no reason.

Boys are never allowed to be in the girl’s cabins, ever. But, once a day we go over, one or two of my friends and me. We usually sneak peek there from the boy’s side, through the woods, to right behind the girl’s cabins. We know which one we want and go in through the rear window. Sometimes we run to the front door, but it is better all around to go the back way. That’s why all the screens in the back windows are ripped out. The counselors staple them back on every year.

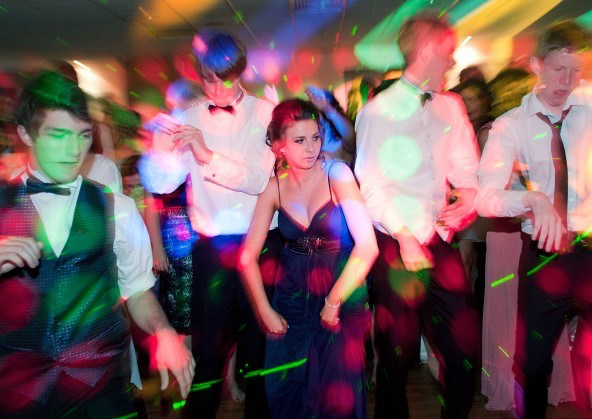

We hang out, talk about life, and chill. We dream up rages, but never in our cabins, always in their cabins. It’s awesome and the music pumps. We just go up and down the walls. Sometimes fifteen people crowd into the cabin, having fun and out of control. We rage every day, mostly during the day, but sometimes at night, too, at least whenever we can. It’s better in the dark when we can turn on the Christmas lights and crazy dance to Skrillex. The counselors hear the music, but they don’t care. There’s music playing all the time. The wrong counselor coming in for a random reason might catch you, so you have to watch out for that.

When people knock on the doors we jump in-between any crack or under the beds. The girls say, hold on, we’re changing, and we just wait, hiding under the beds, or in the cracks where they can’t see you. All the time you’re hiding and you’re quiet so they won’t find you. Most of the counselors just laugh and call you pathetic if they see you. But, they always let you stay.

After the rages we talk and chill again, eat all of the girl’s candy, and then sneak back to our cabins. We’re only there for two weeks, so we have as much fun as we can, playing music and dancing to the beats. It pumps hard every day. It’s not melodic, trust me on that, although one time Logan slowed it down and sang I Did It My Way, and everybody loved it. For the rest of camp whenever we chanted his name he had to jump on a picnic table and lead a sing-along of My Way.

I am the boss of dance moves at the camp dances. There isn’t anyone or anything that doesn’t make me the boss; a picture of the boss busting moves is worth ten thousand words. The girls dance with me because I’m not a douche. The ones who are exactly that think they’re cool, but then nobody really likes them, or only a select few who are just like them. You can’t be the boss and a douche, too.

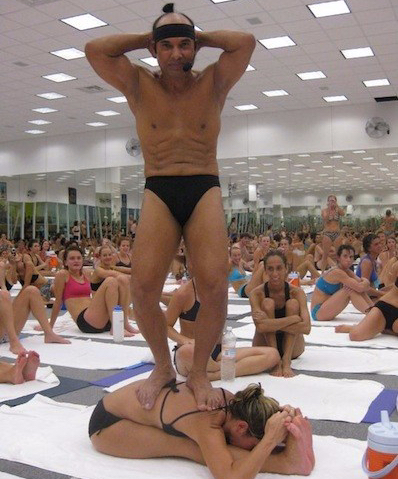

At the dances everybody makes a circle and I squirt into the middle. I break moves, and I’m dead serious about it. I’m out there every dance rocking it. I do the party boy, popping, liquiding, and electric shuffling. One of the counselors is teaching me. He goes to things called raves, like rages, except they’re gigantic, where people get wasted. He says they’re awesome.

My favorite dances are slow dances, of course, because you get to dance in a curve, your arms wrapped around your girl, soft and flowing. Everything is good about that. I love shuffling and going crazy on the dance floor, but it’s a close second. I slow dance with just about everybody, except cabin seven, the youngest girls, who once asked me to dance with them. I said no to that.

It was two or three years ago when I started noticing the chiquita’s at summer camp. At first it was just curiosity. Then it was like standing on the rim of the Rocky River Valley and feeling how great it would be to jump. They were there and they were nice. Being around them felt like something good was going to happen.

Happy girls are the prettiest girls, but some of them, especially the ones who think they’re stars, are mean. When you try to talk to them, they act, like, “Oh, my God, I’m so cool, and you’re so dumb, leave me alone.” They will say, “Just because you know my name doesn’t mean you know me,” and walk the other way. It’s then you know they’re down and snobby. They never smile when no one else is around because they would have to really mean it.

Natalya is one of the mean girls. She isn’t hot, although maybe she is, partly. She’s shorter, not fat, but not like a twig, either. She has some knockers, nice and big, but she wears a butt-load of make-up, which is weird. She prances around, like she is acting it out, and dyes her hair all the time in different colors, black, and then blonde, and then something else. She brought her own little folding table to summer camp so she could put make-up on in private. She wears a ton of it.

If you wear make-up it doesn’t mean you are snotty, but that’s just a thing with her. Most people can only whine for so long, but she whines over stupid things all day. We’re in the same morning classes, after cabin clean up and the inspections, so I know. She’s in my group, and whenever we have to do anything, she whines about it, saying, “Oh, my God, I’m not doing that.” She just wants to sit around and be annoying.

She has a lot of friends, but she has a lot of enemies, too. Logan said she deserves her enemies, but I think she deserves her friends, too. Some of my friends, girls who are nice, hate her a lot. They won’t be in the same cabin with her, even though they are the same age. I know she hates being ignored. I try not to care about her, but I can’t, not always.

The other mean girls, Alexis, Samantha, and Hannah, are all in my morning group, too, which sucks. Alexis doesn’t constantly whine, only most of the time, and she wears shiny bracelets and rings, too. She just wants to sit around and be looked at. Samantha is all drama, way into herself, and I don’t like her at all. Everything she says she starts by saying “Frankly…” She looks awkward when she’s not talking. I don’t even know about Hannah, she’s just kind of weird, glammed up like a puppet.

The nice girls are fun to be around. That’s the big difference about them. They’re not immature about things like having to play sports all day on sport days. They even play the dizzy bat with us between games on the soccer field, at the end the sidelines strewn with us lying on the ground, grabbing for the grass to keep from falling off the edge of the earth. The mean girls sit in their cabin and flame about it, and stupid stuff, like how small their cabin is, even though there are only four of them. Ours has eight of us in it, it’s the smallest boy’s cabin, and we never complain about it, ever.

The mean girls always want to be with the boys who are ripped. All they want to do is talk to them and then talk about them the rest of the time. The nice girls don’t like the boys who are mean and their girls. They don’t get along. There really is a divide and it’s serious. Last year one of the mean girls, Kayla, started cursing out another girl and charged her, and got kicked out of camp. Her parents had to come and get her. That was bad.

The nice girls don’t try so hard to be something they aren’t, slapping on a smile or a smirk. They’re not expert liars. The mean girls always look like they’re waiting to be discovered behind their cover up. But the nice girls, even if they have bandy legs and a lopsided face, when they laugh it’s one of the best sounds in the world.

One of the nicest girls at camp is Lauren, who is tall, has wavy brown hair, kind of long, and is a little chunky, but not like fat. At least, not too fat. She lives on the other side of the lake where it’s the Upper Peninsula. Lauren doesn’t try to be anything. She’s pretty, but not beautiful, not like she’s impersonating somebody, trying to fool you. Instead, she’s really kindhearted and friendly. She stays up at night, like me, listening to music.

Jessica is my age, the very nicest girl of all. She is fourteen, just a month younger and a bit shorter than me, blonde hair, but not dirty blonde. We have known each other for five years. She appreciates everything about me, the whole nine yards. We see each other every day. We go to the secret swings and talk, but I don’t remember about what. You never know what girls are going to say. I just stare at her. I don’t know what she talks about, girl stuff, I think, and her clothes. Anything they wear is fine, really. I heard her say once she likes the Detroit Tigers, and another time she said something about her room. She says all kinds of stuff and I just listen. Sitting in the woods with her at night feels like hanging loose. I never want it to end.

Last summer Raymond, the night guard, who is the weirdest man, was in the bushes when I was walking to the crapper from the swings after a night with Jessica. He was standing in the dark watching me, and my friend Logan saw him and started screaming at him, “Get out of here, man, what do you want?” He also used some select words. It was the funniest thing, because most of the time no one can talk to Raymond like that.

Raymond is the night guard, not a counselor, or even one of the camp commanders. His hair is long and greasy, he always wears a baseball cap, and he smells terrible. He’s one of the older adults, for sure in his 50s, and he told us he’s an ex-Spetsnaz. Titus was stung in the ear by a hornet once, and was crying, and Raymond told him to “tough it out.”

He sleeps during the day and patrols the camp at night, and will stand behind your cabin, just looking in at you for a long time, like a freak. He’s very patient. Nobody wants him chasing you when you have snuck out. You can’t break away from him, ever; he’s just a beast. He has a birch branch that he whips your feet out from under you when you’re running, and will seriously manhandle you when he catches you, which is every time.

The best night of camp is the night of the manhunt game we play with the counselors on the 4th of July. It’s called Nazis and Jews. The older campers are the Jews and the counselors are the Nazis. We call it that because the Jews run from the Nazis. The kids have to go to bed. They aren’t allowed to play. We start running as soon as it gets completely dark, so we have a chance, and then the counselors come after us. If they catch you they railroad you back to a jail where you have to sit and wait.

You can try to get away, but it’s hard because the counselors who catch you are the strong, fast ones, and the ones who don’t catch you are the slow ones, the ones who are mostly unfit. The strong ones don’t like it when anyone makes them look bad by busting out. You can try to break free when no one’s looking, but if they grab you then you have to stay longer. The longer you sit there the less chance you have to win Liberty Dollars for the auction after the game, which isn’t a good thing. It is intense. I am dead serious.

One summer during the manhunt Simon, who is from Maine, jumped out of a tree on me. Whenever he talks it’s with a slurry, toothless accent. He was ten feet up in a quiet, dark shadow where I couldn’t see him, and he jumped down and tackled me. I got up and ran, but he started chasing me. He was like a monster, coming to get me, and I ran into a branch. Everything just went SHING! I almost got knocked out because it hit me right in the face and tore my neck, which really hurt. There is still a scar on my Adam’s apple to this day.

On another game night Matilda, who plays for a college basketball team and is seriously fast, blind-sided me, decking me. At first I wasn’t sure what happened. I didn’t mean to, but when I got up I tripped her, and started running away. You try to run away whenever anyone catches you. When she caught me I fell on the ground like I was out cold. She was forced to drag me by my arms and legs. While she was dragging me, huffing and puffing, I noticed a large lump on her chest. When I asked her what it was she gave me a sly look and said, “It’s a tumor, I have cancer.” I couldn’t believe it. She seemed so healthy. I jumped to my feet so she wouldn’t have to drag me. While we were walking the tumor started to jerk back and forth. I didn’t know what to do, since it wasn’t anything we’d learned about in first-aid training. I thought she might collapse. Then, just as we walked up to the jail, her baby pet gerbil poked its head out of her bra.

Last summer the jail was inside the art house, where all the supplies and costumes are stored. It’s at the farthest end from the sand dunes. Makayla was the guard that night, and although she isn’t very big, she’s strong. There are two rooms, so she had to patrol both of them. We had to sit in chairs and be quiet. If you talked too much you had to sit there longer. If you got up from your chair for any reason you had to stay in there longer, too. You could try to escape, but it wasn’t easy. Makayla would hit you, not really hard, but hard enough, with a twine broom, usually with the soft end. She would push the broom down on you and yell the whole time.

You don’t want to try escaping too many times, either, because if you try a couple of times and they catch you each time, they might kick you out of the game for the night. It isn’t fair, but that’s what they do if they get annoyed about it. If you sat there quietly, or told Makayla you’d be good, sometimes she let you out before the others.

The game starts once it gets dark and everybody is assembled at the bonfire pit in the sand arena. The counselors change the game a little every year. One summer whoever was a Jew child had to go out to find passports for their family. That was the main prize. When they got caught, and they all got caught because there were traps everywhere, the rest of us, their family, had to break them out of jail somehow. It was like capture the flag, but trickier.

This summer the counselors took us to the dining hall, closed the doors, darkened the windows, turned off all the lights, and made us sit on the concrete floor. There were two people giving news broadcasts, but then a counselor warned us they were going to censor the station. It got quiet. You couldn’t hear anything.

When the counselors came back they were dressed in black, charcoal from the bonfire smeared on their faces, and screaming, acting like they were mad. They split us up into groups and gave us directions. We had to find books and save them from being burned. They gave us clues and we had to find them. They weren’t real books, just pieces of paper. The more we brought back the more Liberty Dollars we got for the auction. The more of us in our group, our family, that got caught the more of our Liberty Dollars were taken away.

The papers were scattered around the camp in the pockets of a couple of special counselors, who were hidden in the forest, and kept moving around. You had to find them and when you did they would give you the paper. But, sometimes you had to beg them. If the Nazis captured you they would take the paper away from you, rip it up right in front of you, and you would have to start all over. A lot of people hid them in their shoes, or their underwear, or different places no one would look.

It can be a dirty game. One time I was by myself, not far from the art house, but on the edge of the woods, and one of the counselors came walking past, and I dropped flat. I was lying in a bunch of crap, leaves, twigs, bugs, mud, and stuff, and he just walked right up to me, but didn’t see me. I was, like, “Oh, man.”

Everybody gets the same number of campers for their group, and they are your family. The mom and dad of the family are the two oldest from the girl and boy side, and the children are the trickles from the other cabins. You have to find the books, but you have to protect each other, too. If anyone in your family gets sent to jail you have to rescue them. But, it’s best to be careful, so that you don’t get caught yourself.

They called us out family-by-family and yelled at us if we didn’t listen. They were hitting the floor with brooms, yelling at us, dressed all in black. Most of us were dressed in black, too, or camouflage, because it gets intense. They gave the moms and dads a lit candle, lined us up, and marched us to the sports field. They were telling us the rules, when Gregory, who has an anger problem, and wasn’t even in my family, snuck up behind me and snapped at me because I was laughing, “Shut up!” and then slammed me. I slammed him back on the ground. I was, like, “What the hell?” The counselors were shouting, “Gregory, get over here!” and they started chewing him out, because I hadn’t done anything.

Gregory has crazy anger problems. He might not make it. His brother used to come to the camp, but he was kicked out one year for the same thing. They called his parents to pick him up and he has never been back. That’s the worst thing that can happen at camp.

The counselors were being all serious, spitting out commands, when out of nowhere, out of all directions, they just started screaming and sprinting at us, without even telling us that it was starting. We booked it in every direction. That’s how the game started. It was crazy.

I had already planned to go with my friends, because you don’t really want to stay with your group. It’s stupid then, since you’re just trying to have fun, anyway. We hustled to one of the boy’s cabins and hid there, and then started running around, dodging the counselors. Some of them are fast, and there are two girl counselors, too, who can catch you if you don’t see them coming and they are already sprinting towards you.

You can push the counselors away, out of your way, but not punch them, although you can punch them, just not all of them, only the ones who don’t care. Your friends can come help you, and if the counselors try to catch both of you, you have a good chance of getting away, because they can’t get both of you at the same time, no matter how big they are.

The counselors tackle you hard when they want to. They can be stealthy rockets and they don’t mess around. Sometimes they’ll use you as a distraction so they can catch someone else. If they’re your counselor they’ll cut you some slack. You act like you’re getting caught when one of your friends is walking by, and yell, “Help me!” and your counselor will throw you to the side and run to get them, and you can then dash free.

I had to help when Noah explained he needed me to go along with one of his plans. When I was little I would slip into his cabin and his friends would let me sit on their beds and give me candy. Besides, he had me pinned down. He pretended to capture me, but he really wanted to capture one of my friends. He had his own reasons. They are usually not going to let you go just to capture somebody else, because then you can run off. But, I did what he wanted, and I begged one of my friends, “Dude, come help me,” and Noah let me go and took him.

This summer the jail was on the sports field, which was a pressboard box used to store basketball backboards. It was small, the size of a dining room table, but tall and deep to the back. Last summer the jail cell was the boy’s bathroom. It was dark and clammy, the light bulb missing, with only one door, so it was hard to escape from. We had to sit in there with the daddy long-legs and rotten smells.

The pressboard box was even worse. It was out in the open with a pole lamp over it. The counselors squeezed eight people in there, around the edges, and then made more people stand in the middle like cattle. They nailed two-by-fours to the sides so we wouldn’t spill out. Everybody was packed tight inside it. You could try to crawl out, but they would have already gotten you by then.

We escaped when some counselors grabbed new runners and were bringing them in, but there wasn’t any room left because it was so crowded. Someone pushed us out. We had a couple of seconds of leeway. They can’t just grab you again that minute, so we ran into the forest to the Hill of Crosses.

The Hill of Crosses is on a small dirt hill in the woods. There are trees all around it, and nothing but crosses on the hill, hundreds of them, some bigger than life. Everybody’s parents know all about it. It has something to do with their past. It’s been there a long time, but no new crosses have been added so long as I can remember. There’s a white fence around the hill and a gate, but it’s never locked. We go there for fun sometimes, to talk, and chill, because almost no one ever goes there anymore, and it’s secluded.

We were cutting through the Hill of Crosses, talking out what we were going to do, when Lovett, who is very fast and really fit, jumped out of a sand dune right at us, waving a flashlight. We just flipped out, everybody started running, none of us going the same way. Somebody smashed into Lovett, who singled out Mark for it, running after him.

A lanky kid named Norville, from another cabin but who was with us, sprinted to the border of the camp where there is a crappy old fence. He didn’t know it was there and when he jumped on it he got all tangled. He ended up stuck on it, his hands were gashed, his clothes ripped, and he couldn’t get off. He was bloody after that, not like gushing, but it was bad.

Later, when we all found each other, we saw Lovett with his big flashlight, looking for Mark. We lay down in the sand; we were so afraid, but he ran right past us. We stayed there behind the little hill where we hang our clothes after coming back from the lake, and then snuck back into our cabin. We were sitting on our beds, laughing, but Mark was freaking out. He was so afraid he got on his knees, put his hands together on his bunk bed, and started praying out loud. He was praying there, crying, saying, “I don’t feel good,” when Lovett walked in.

“What’s wrong with Mark?” he asked.

“I don’t feel good,” Mark said, and walked outside the cabin and threw up. He tried to throw up in the trashcans, at least it looked that way, but he didn’t get any in the trashcans, at all. The next morning we dogged Mark, because he’s an idiot, but all he said was he really didn’t feel good, anyway.

After Mark threw up we heard one of the counselors squawk on the loudspeakers that the game was over. That’s how it really ends. They broadcast all during the game, about how much time is left, and what we have to do, and then it just ends. I don’t know what time that is. I don’t wear a watch at camp. Everybody just has to report to the dining hall.

After the game is over we get a five-minute break to mess around, and then we all go to the hall, laugh with our friends, and tell them how crazy it was. We’re still getting our breath back when Father Elliott starts his talk. He always speaks after the game. This summer he told us about Siberia, how he went on a memorial train ride there, to commemorate our grandparents who were taken away by the Communists in the 1940s.

He talked about the train cars, how there were so many people in the freight cars that nobody had any space to move around in, and how they had to go to the bathroom in the train itself. He was very serious. It was kind of sad, actually, how serious it was, but I was glad he told us about it. He had pictures on his laptop, lots of them of the little broken-down villages where people had to live in the freezing cold. I remember one picture, there were wooden railroad tracks, old rusted bolts, and the snow was blazing white. The tracks were all nasty and messed up. I don’t know why I remember that one. He said we should be thankful we didn’t have to go through that, that we were lucky.

Father Elliott is our priest at the camp. He runs the religion classes, says mass, and organizes the Faith Nights. We build bonfires all around the camp for Faith Night, in the dunes, by the art house, and everyone goes to one of the bonfires with their morning group. Our two counselors have a list, they ask us questions, and we talk. I used to think it was stupid, but I like some things about religion now. Some people take it as a joke. They are smart-asses.

In my class at St. Mel’s I hate my religion teacher, but at summer camp I try to express myself. Some of the questions are dumb, but a lot of them are intriguing. How do you see God? What does God mean to you? How do you communicate with God? When I was a kid they taught us to go to church and pray, and everybody would be happy. But, is that truly enough, to pray once in awhile, and that will please God? I’m not sure.

Father Elliott goes to each group on Faith Night carrying chairs for confession. I don’t really like that. You’re sitting by your fire, talking about God and all, and he comes by with his two folding chairs. He doesn’t make you confess, but you basically have to. You have to sit face-to-face with him in the open. He stares straight into your soul while you’re giving confession. I don’t want the priest to know it’s me because you see him every day. You know he thinks of you differently afterwards, at least for a few days.

This summer we almost didn’t play Nazis and Jews. We heard rumors the camp commander wanted to stop it, or change it, but the counselors said you couldn’t just stop it. It’s a legend at camp. It’s the most fun night of the two weeks. It was probably somebody’s parents, the counselors said, complaining about calling the manhunt game Nazis and Jews, or something like that. Everybody was worried. At least we got the game back, and it was the same, although we might call it something else next summer.

They were playing it when I first started going to camp. I used to want to play it so bad then. When we were kids in the long barracks we would get together, go somewhere, and play our own manhunt game for hours. We stood in a circle and chanted “bit, burp, poop, you, are, not, it” until only one kid was left, and he was it and had to go and catch people. If you saw one of your friends you could try to tag him and he would be it.

One summer my third-best friend Adrian was it and he was mad because he had been it twice that day. “I‘m not playing anymore,” he said. We said, “Stop being a baby and just be it.” He started chasing Luke, who was still really small. He ran and Adrian tore after him, and then slammed him onto his back. Luke broke his arm and had to go to the hospital. He wore a cast for the rest of camp, which was bad. Adrian told everybody he was sorry. He was crying about it and explaining he hadn’t meant to do it.

Summer camp goes by fast. You wake up one morning and it’s over. Where did it go? We’re always wasting our time, but we never waste a minute. You’re hanging with your friends, everything is carefree, and then suddenly you have to go back to your normal life. It’s gone, it’s done, and you have to wait another year. You go see your girls and they’re all teary. You hang out with your bro’s and everybody is kind of sad.

After breakfast we raise the flags one last time. I know we won’t be the ones lowering them later that night and nobody feels good about that. We go back to our cabins, get all our stuff ready, and then everybody’s parents start arriving. We go to the bonfire pit and sing songs one more time, like The Cat Came Back the Very Next Day and Tin Tan Tin. I don’t know what the girls sing. It is something like “Tick a lick a lick, per diena zirgele, I am alone.“ But, the truth is, my friends and I don’t really sing anymore. When you’re a kid it’s fun, but now it sucks.

We always sing one last song. Everybody gets in a big circle at the end, the whole camp, after the awards are given out, and our arms all crossed together we sing I’m Leaving on a Jet Plane, and then say a prayer. It’s really sad, and then it’s over, and you say goodbye to everybody.

The next year when it’s time for summer camp again you are jonesing, it’s like getting the jitters. All the same people are there, all your girls and your cabin, and everything we do. It’s just a great experience. When I’m older, after my last year, when I’m not allowed to be a camper anymore, I’m going back as a counselor. That’s for sure, at least until I finish college and have to get a real job.

I was the top dog at Nazis and Jews this summer. The next day I ran my stack of Liberty Dollars to the auction. The camp commander stands at a podium with a wood mallet. There is a chalkboard behind him with a list of all the things you can get and everyone starts bidding. There are t-shirts and baseball hats, breakfast in bed, and counselors cleaning your cabin. Sometimes it’s a mystery box, which can be good, like roasting marshmallows for two hours, or it can be not so good, like cleaning the urinals.

There’s stargazing with another cabin of your choice, which is always obviously a girl’s cabin, and that is a good thing. But, I put everything I had, all of my Liberty Dollars, on the first shower. Saturday was the night of the formal dance and I wanted to look my best for it. I made absolutely sure nobody outbid me because it was do-or-die for the hot water.

You get to shower first, all by yourself, for as long as you want to. You’re in the shower and nobody can get you out. They post a counselor to stand guard at the door and they don’t let anyone in except you, and you can use as much hot water as you want. There is only so much of it at the camp, but you can take it all, and everybody else is left with the cold remains.

Oh, yeah, that is what you always do, because everybody else would do it to you.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”