By Ed Staskus

Dave Bloomquist ran the show at the Plaza Apartments, trying to make it work on the near east side, on the fringe of downtown. The apartment building we called the house was on Prospect Ave., a $.25 fare on a rundown Cleveland Transportation System bus about five minutes from Public Square. The ghetto was uptown and all around us. Liquor, deadbeats, hookers, old cars, and boarded-up windows were the order of the day. The house, however, was its own enclave.

Dave was from Sandusky. “The town, which is sluggish and uninteresting, is something like an English watering-place out of season,” Charles Dickens wrote after visiting it. A hundred years later it was known for Cedar Point, an amusement park on a peninsula jutting out into Lake Erie. After high school Dave moved to Cleveland to study visual and fine arts at Cleveland State University.

“Art held a natural attraction for me, and it was something I wanted to pursue,” he said. “My dad was an electrician. II helped him run wires and other simple tasks. I also worked during college, renovations, painting, things like that. After graduation, my business partner and I scraped together a down payment on the 48-unit Victorian-style Plaza. We decided to restore it ourselves.”

Dave was always in in and around the building. Whenever anything went wrong, it didn’t take long to find him. He was the owner, superintendent, and maintenance man. If he wasn’t nearby, his ex-wife-to- be, Annie, tall and slim, her hair done up in braids, was right there cooking, cleaning, and taking care of their baby boy. Built in 1901 for middle-class residents, something was always making trouble at the Plaza.

“We learned to sweat pipe, patch the roof, and fix windows,” Dave said. “We had to operate with just rent money. We couldn’t afford to call on anyone for help.”

Back in the day Upper Prospect was the second most prestigious place to live in Cleveland, next to Millionaire’s Row on Euclid Ave. Prospect Ave. and Euclid Ave. were where to be, the smoking rooms of the city’s economic and social elite. Most of the homes on Prospect Ave. were brick two-story single-family houses in the Italianate style. The street was lined with elm trees.

By the time I moved onto Prospect Ave., as the 1960s leaked into the 1970s, all the rich folks were long gone, and Dutch elm disease had killed most of the trees. It was killing most of the elms in all but two states east of the Missouri River. Those that hadn’t died were being sprayed with DDT or removed. The entry point for the bug was Northeast Ohio in 1929, on a train bringing in a shipment of elm veneer logs from France. The train stopped south of Cleveland to load up on coal and water. Not long afterwards elm trees along the railroad tracks started to die. The elm bark beetle doesn’t kill the tree, but the fungus it carries is deadly.

There were rowhouses scattered among the single-family homes, which included the Prospect Ave. Rowhouses that Dave was throwing his eye on. He had more than enough work on his hands, but he was a no slouch go-getter. Preservation and restoration efforts on Upper Prospect were beginning to pick up steam.

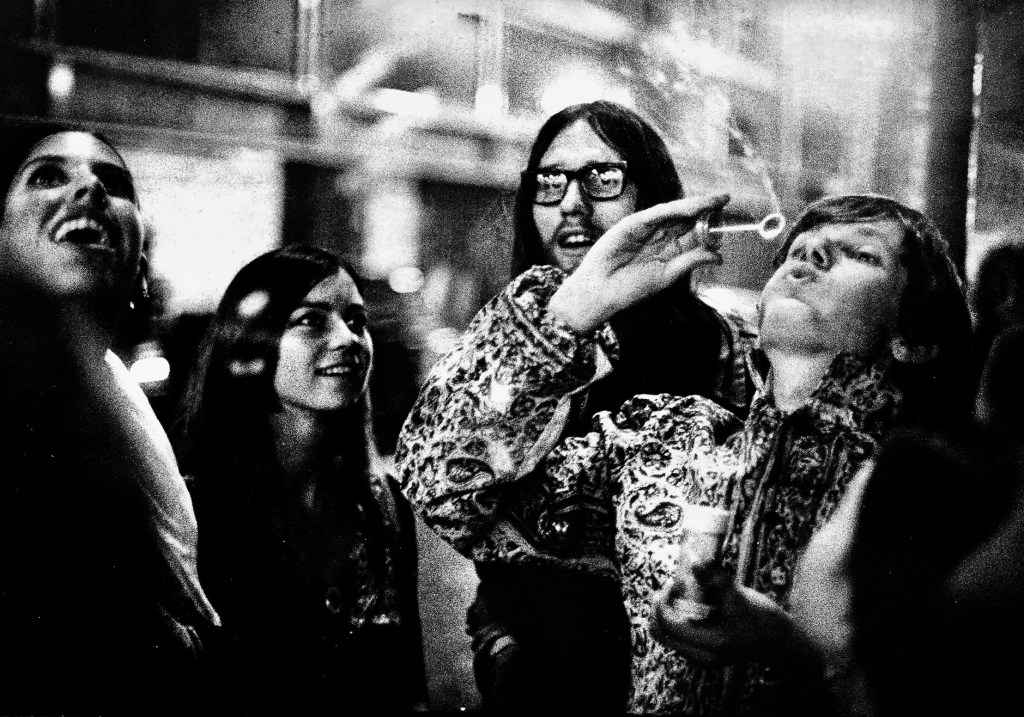

Before moving in I walked to Mecca Keys on Rockwell Ave. off East 9th St. and had a key for my apartment made. The Plaza was home to students, secretaries, both beatniks and hippies, machinists, artists, bikers, clerks, musicians, court reporters, dogsbody men, anarchists, and writers, some shaking and baking, others simply doing their best to keep the wolf away from the door.

“We were urban pioneers before the term was coined,” said Scott Krauss, a drummer for the art-rock band Pere Ubu. “Like the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead had their band houses, we had the Plaza.”

“There were scores of wonderful community dinners, insipid and treacherous burglars,” Dave said years later when it was all over. “Innocence was lost. There were raucous outrageous parties. Families were formed and raised and there were tragic early deaths of close friends. But music, art, and life were in joyful abundance all the time.”

There was plenty of old-fashioned seediness, too. “I remember coming home at four in the morning and there would still be people in the courtyard drinking beer and playing music,” said Larry Collins. “We would watch the hookers and their customers play hide-and-seek with the undercover vice cops.”

One of the first friends I made there was Virginia Sustarsic. I had seen her around Dixon Hall up the street when I lived there before I moved to the Plaza. She was close to John McGraw, a trim bohemian who lived alone on the third floor, read obscure European poets, drank Jack Daniels from the bottle, and drove a 1950s windowless Chevy panel truck. It was a black panel truck.

Virginia had interned at the Cleveland Press, worked on Cleveland State University’s’s student newspaper, and wrote for the school’s poetry magazine. Since she was settled in at the Plaza, was friendly, and worked for herself, she made friends easily, and I subsequently made friends at the Plaza by hanging around with her.

She knew all about art. I didn’t know much about anything. When she showed me a reproduction of a Jackson Pollack painting, I thought, what a mess. When she showed me a picture of an American flag by Jasper Johns, I found a ragged old flag and thumbtacked it to the wall at the head of my bed. I thought I was being au courant.

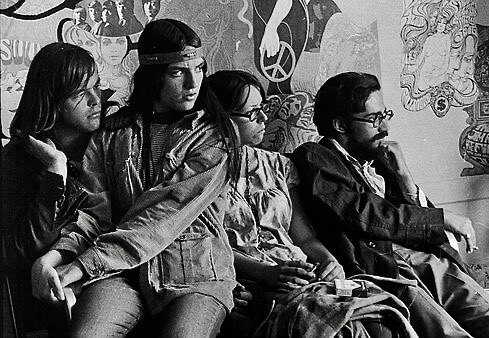

Virginia made candles, incense, and roach clips for a head shop on the near west side. The owner of the shop, Jamie, was a little older than us. He wore fake glasses to disguise a pear-shaped nose. He wore a red checked bandana and liked to go barefoot. He pulled up in a mid-60s VW T2 bus, Virginia delivered the goods, he would say he had a great idea for going someplace fun, as many people as could fit would pile into the Splittie, and he would drive to a park, a beach, or a grassy knoll somewhere.

Jamie always played The Who’s “Magic Bus” at least once every trip, there and back. “Thank you, driver, for getting me here, too much, Magic Bus, now I’ve got my Magic Bus.” The speakers were tinny, but the volume made up for it.

We went to see “Woodstock” the movie at a drive-in, since none of us had gone to the music festival. Virginia’s roach clips came in handy. The Splittie’s back and middle seats could be pulled out. It was useful at drive-ins, backing the bus in to face the screen, some of us in the seats on the ground, others in the open rear of the bus, and Jamie with his gal on top of the VW, an umbrella at the ready.

Nobody wanted to be sitting behind Mike Cassidy, who was skinny enough, but had a massive head of long electrified red hair. Virginia got him a shower cap to keep his mop top under control, but he refused to wear it.

Virginia was hooked on photography and showed me the ropes, letting me use her camera. When a photography contest was announced at Cleveland State University, she entered a picture she had taken in San Francisco. I entered a picture of Mr. Flood.

Bob Flood lived on the second floor, like me. None of us knew what he did, exactly, although he wore a hat suggesting he was a locomotive engineer. Virginia thought he was a professor of some kind. Everybody called him Mr. Flood. Nobody knew why. He was a lanky careful man, sported a shaggy looking beard, was divorced, but had visitation rights to his two children, who came and played in his apartment on weekends.

My picture was a portrait and Virginia’s a full-scale shot of two homeless men in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, passing a bottle of booze between them. The trees in the background disappeared into a triangle. After I won the blue ribbon, Virginia went to the Art Department and talked to one of the judges. She told him she had been trying to conjure the Pointillism of Georges Seurat.

“Well,” he said. “The portrait and your picture were our top picks. But yours was kind of grainy.”

“That was the whole point,” she groused.

Virginia’s best friend at the Plaza was Diane Straub. Diane had a straight job. She was a secretary downtown. She got up every morning, got on the bus, went to work, and came back at night. Monday through Friday she took care of her apartment and her cats. On weekends she got loose. She got dressed up as Bogie’s old lady.

Bogie was Diane’s live-in boyfriend. He was fit and strong and always wore black, tip to toe. He had a Harley Davidson he kept in the back lot. Nobody ever tried to steal it, because everybody knew that would be a big mistake.

He was one of the Animals, although he and the other Animals had been forced to go freelance. They used to have a clubhouse, its walls pockmarked with bullet holes, on Euclid Ave. in Willoughby, until the day the Willoughby police raided it. “The police couldn’t get anything on us, so they hot-wired the landlord to force us out,” one of the Animals, Gaby, told the Cleveland Press, which was the afternoon newspaper. “We never did anything worse than use the clubhouse walls for target practice.”

Gaby knew full well there was more to the story. His biker clubmate Don Griswold had been arrested the day before for being involved in a shooting with members of Cleveland’s Hells Angels that left two dead. “The Angels were going to take care of me if the cops didn’t do it first,” he said. “Misery loves company.”

The spring before my first full summer at the Plaza, Cleveland’s Breed and the Violators got into it at a motorcycle show at the Polish Women’s Hall southeast of the Flats. The 10‐minute riot with fists, clubs, knives, and chains left 5 men dead, 20 Injured, and 84 arrested. The dead were buried, the injured rushed to hospitals, and the arrested hauled away to the Central Police Station on Payne Ave. The Black Panthers were always demonstrating outside the front doors, but they had to make way that day. Armed guards were posted in the hallways of the station as a precaution. When the injured bikers recovered, they were arrested at the hospital’s exit door.

Art Zaccone, headman of the Chosen Few, said the fight broke out because of trouble between the two groups going back to a rumble in Philadelphia two years earlier. The biker gangs didn’t ride on magic busses. They rode hogs. They made their own black magic. They had long memories and nursed never forgotten or forgiven grievances.

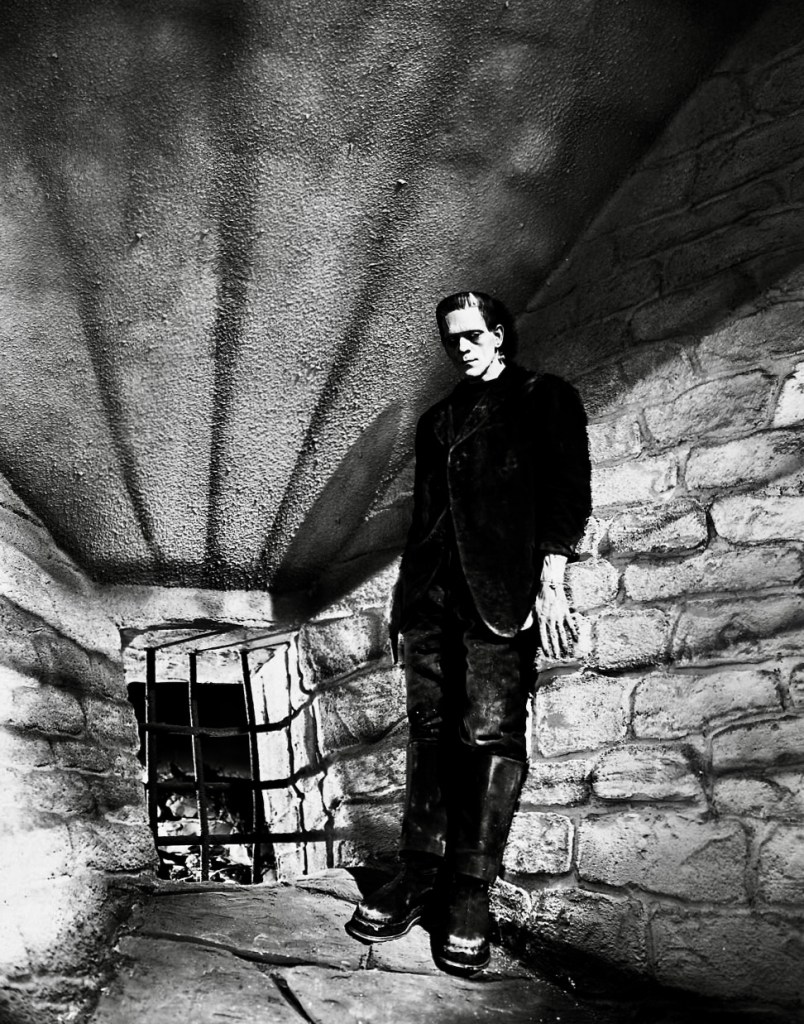

After Bogie moved out, Diane took up with Igor, a math wizard. He was tall, had long wiry hair, and played air guitar. Even though he was egg-headed about numbers, he often looked like he was only half there. He was vivid but baffling.

“We all thought he was tripping a lot,” Virginia said.

I lived in a back apartment on the second floor, although I avoided the back stairs and porches. They were falling apart in their old age. Virginia lived in a courtyard-facing apartment on the same floor and an older Italian couple, Angeline and Charlie Beale, lived in the front. They always had their apartment door open. Charlie was short and stout, a retired mailman. He read newspapers and magazines all day long. Angie was short and stout, too. She stayed in the kitchen in a black slip cooking and drinking coffee from a Stone Age espresso machine.

They had an orange and green parrot. Whenever Angie spied Virginia walking by, she called out, “Oh, honey, come in, let me see if I can get him to talk to you.” She would coo and try to convince the bird to talk. He never did, even when she poked him with a stick. When she did, he whistled and squawked, sounding offended.

“How long have you had that parrot?” Virginia asked, thinking they were still training him.

“Oh, we’ve had him for sixteen years, honey.”

Angie and Charlie went shopping for foodstuffs twice a week. They walked down Prospect Ave. to the Central Market. “They always started out together, but ended up a block or more apart,” Dave said. They both carried handmade cotton shopping bags, one in each hand.

The Central Market was on E. 4th St., nearly two miles away by foot. The only people who went there were people who couldn’t get to the West Side Market. It was grimy and the roof leaked. “Some panels are out, and when it rains, we got to put plastic tarp down, which looks like hell,” said produce stall owner Tony LoSchiavo.

“She always ended up walking twenty feet behind him,” Virginia said. “A couple of hours later, same thing, both of them their two bags full, he would be walking twenty feet ahead of her as they came back to the Plaza.”

He waited at the front door, holding it open for her. She trudged up, he followed her, and the parrot every time said, “Welcome back!” when they stepped into their apartment. Angie returned with vegetables like asparagus and nuts like filberts for the thick billed brightly colored bird.

Most of the tenants at the Plaza were on good terms with one another. Many of us were single and sought out company up and down the floors and down the hallways, especially in January and February when snow piled up unshovelled. We swung by unannounced and chewed the fat.

“Friends would just drop in,” Virginia said. ”All the time.”

One Siberian Sunday afternoon Mr. Flood’s children were visiting and went exploring in the basement. They found a Flexible Flyer. Their father bundled them up and carried the sled outside. When they got tired of pushing each other back and forth in the parking lot, they found a shovel and scooped snow onto the back stairs as far up as the first landing. They shoveled enough snow on the stairs to make a ramp and spent the rest of the day running across the landing, throwing themselves on the sled, racing down the ramp, and zooming across the icy lot.

Mr. Flood and I watched them from the second-floor landing. “They’re up to snow good,” he said when they hit bottom, bumped upwards, and got some air under their sled. Mr. Flood was the kind of man who talked low, talked slow, and didn’t say too much. He wasn’t, for all that, above cracking a joke.

“They’re on their own magic carpet ride,” I said.

“Animal crackers!” the children whooped back at their father, living it up without a care in the world.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”