By Ed Staskus

“Release your bones,” said Vera Nyberg.

She sat cross-legged on a one-step-up platform at the front of the room, scanning the sparsely attended late afternoon class as everyone finished their yoga poses and settled down on their mats.

”Release your bones into the earth,” she said. “Feel the support of the earth beneath them.“

John Cerberus rolled out of shoulder stand and following her bidding lay down in corpse pose, squeezing his eyes shut and exhaling strongly. He made a mental note to tell her two things.

The first was to not teach any more classes wearing the leopard print Capri’s and black sports halter she was wearing. It wasn’t attractive. She was only a temporary teacher living in the dormitory, but he expected her to know better about how to dress for class, even though it wasn’t a dress code as much as what was understood to be appropriate at the center.

The second was to wear contacts when she was teaching. The cat eye frame glasses she was wearing made her look old-fashioned and weird.

He made another mental note.

He would have to re-read the poison pen letters slipped under his office door earlier in the month, week, and day. There was something about the way they were written that reminded him of somebody, maybe like e-mails he had gotten a year-or-so ago. It was probably nothing, he reasoned, just another malcontent from the Amazing Grace days.

They were the last mental notes made by the Asana Director of the Kritalvanda Center for Yoga and Health.

The large room with its scattered practitioners lying prone on their mats was filled with dusk, the lights dimmed almost off, the late November sun setting on the other side of the row of yew hedges outside the floor to ceiling windows.

He relaxed uneasily into the last pose of the hatha class. It had been a demanding ninety minutes at the end of a long, demanding day. Maybe savasana wouldn’t be so bad today, he thought. He let his feet fall out to the sides and turned his arms outward, palms face up, trying to let go of his body.

He made an effort to quiet his breathing.

Around him the guests and day-pass visitors were lowering their bodies into dead man’s pose, what the Sanskrit word savasana was better known as, letting their eyes sink back and releasing their thoughts. Lying there they looked peaceful, Vera thought, giving the room a last once-over.

“Release your jaw and soften your eyes and tongue,” she said, easing the class inward. “Sink into the surrender of no thoughts, no ideas, into the you as you are in yourself, into the world as it is in itself.”

She closed her eyes, letting stillness envelop the room, and started counting her breaths to one hundred, which would take about ten minutes. Afterwards she would guide everyone back to a seated position and bring the lights up again for the end of class.

Corpse pose was hard for John Cerberus, a state of being neither awake nor asleep. The practice of bending, stretching, and twisting the body suited him, as did dead to the world sleep, but not the middle space between effort and sleep. He generally shunned the void of corpse pose unless he was taking somebody else’s class.

There was something, sensations, or memories, at the core of his body he knew better to avoid.

As he breathed to bring his thoughts to a standstill, he became aware someone was behind him, squatting down, large hands at the side of his head, massaging his temples. He was mildly surprised. Vera Nyberg hadn’t struck him as the kind of teacher who proffered head and shoulder savasana massages. She was schooled in Ashtanga Yoga, a more severe practice than most.

The fingers of both hands, one on each side of his head, moved from his temples down to the base of his neck. The sides of her forearms picked up his head and hands cradled his neck. He opened his eyes slightly and peeked backwards.

It wasn’t Vera Nyberg, after all.

John Cerberus started to smile, but then a knee pushed his left shoulder hard into the ground, and before he could react, his head was jerked sharply to the right and his neck snapped.e was surprised

Vera slowly opened her eyes taking her one-hundredth breath. Every day a little bit dying, she thought, something she heard Pattabhi Jois say at a workshop in New York City the last time he visited there. Jois said that corpse pose was a hard posture to master, quieting the mind and body.

“Most difficult for student, not waking, not sleeping,” he said in his broken English. “If student does not get up from savasana, or lifting student up is like a stiff board, savasana is correct.”

After everyone rolled onto their sides, then leaned up and were sitting cross-legged, she thanked them for coming to the class, reminded them about the center’s weekend activities, especially the back bending workshop she was leading Sunday morning, and smiling broadly said, “Happy weekend, everyone.

“Namaste.”

It was only after she had straightened up her area, tucking her iPod and water bottle away into her duffel, that she noticed the body still lying in corpse pose. Tossing the bag over her shoulder, she walked over, recognizing John Cerberus. As she bent down to touch him on the shoulder she noticed there was a small bright yellow flower that looked like a bird’s foot on the center of his chest.

His breath was neither rising nor falling, and when she looked him in the face, his head akimbo, his features were ashy and his unseeing eyes rolled up and back in their sockets.

She reached into her duffel bag, fumbling to find her iPhone.

Sam Fowler of the Wareham Police Department was lifting a pint of Backlash Holiday Porter to his lips when his cell phone began chirping where he had laid it down next to the plate of cod and chips in front of him. He was sitting at the short end of the bar at the Gateway Tavern and Grill. He looked at his Samsung in disgust, checked the incoming number, and then took the call from the Medical Examiner’s Office.

After listening for a moment he said, “OK, ask the Falmouth guys to keep a lid on everything until I get there. I’m just finishing something up here that can’t wait and when I’m done I’ll be on my way. How do you spell the place?”

He flipped open a spiral notebook.

“All right, I’ve got it. It sounds like it will be about an hour-or-so drive. I should be there by nine-thirty.”

He pushed his Holiday Porter away, asked the bartender for a glass of water, and methodically began eating his dinner. The cod was seasoned with salt, pepper, and lemon. He knew nothing about the Kritalvanda Center. He would have to call the station and let them know what was going on. Maybe Ginny Walther would know something. She was working the night shift at the dispatch desk. He had heard talk that she was into yoga.

An hour later, halfway to Wood’s Hole on the coastline of Buzzard’s Bay, an extra-large to-go JoMamas at his elbow, Sam Fowler called Ginny Walther and filled her in. He asked her if she knew anything about the Kritalvanda Center.

“I’ve been there a dozen times, or more, mostly one-day trips,” she said. “You can take any of the classes and workshops they offer on that day, and the day includes breakfast, lunch, and dinner in their cafeteria, although I have to warn you it’s all vegetarian.”

Sam Fowler’s scowl was audible over the phone.

“I spent a week there last year, on my vacation, on a retreat. It’s a wonderful place,” she said, “It couldn’t have been anyone there, they wouldn’t kill anyone.”

“Somebody was there,” he said.

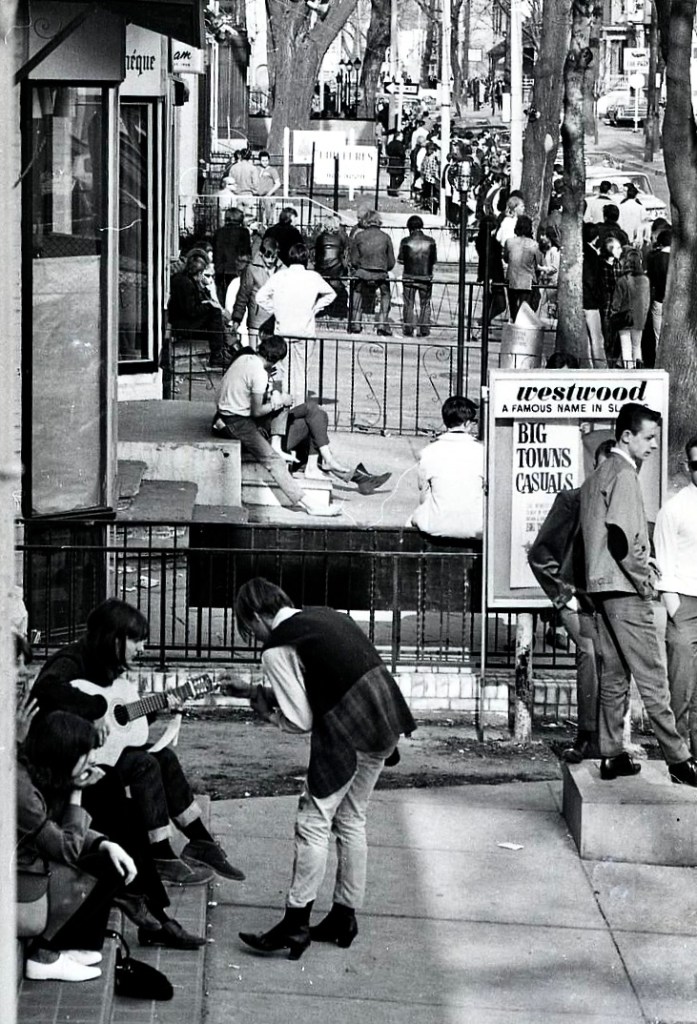

What he found out from Ginny was that the center had its beginnings as the Yoga Society of Cape Cod in the early 1960s, in a derelict Shaker Trustee Building outside of Falmouth, its hippie residents living a communal life. As the ashram grew, which is what the residents called it, they outgrew the two-story saltbox building.

Twenty years later they bought a shut down Franciscan seminary on the peninsula northwest of Wood’s Hole and rehabilitated it to become the Kritalvanda Center.

“Since then they’ve really grown, because yoga has gotten popular,” Ginny said. “Almost 30,000 people cross the bridge every year to go there. They built an annex sometime ago, then a Wellness Center just this summer, new locker rooms, they have their own beach, hiking trails, and even a labyrinth.”

“Why would anyone want a labyrinth?” he asked. “You get lost in them, right?”

“No, it’s not what you think,” she said, “It’s for walking meditation and inspiration, for finding yourself. You should try it while you’re there.”

Steering with his knees he rummaged in the center console organizer of his SUV and pulled out a new recording by Maria Schneider. He liked her large jazz ensemble work, which he had heard her band play in a club in New York City, but this one was different. For most of the rest of the drive Sam Fowler listened to it, but the more he heard of it the less he liked it.

The music was not so much jazz than a kind of fusion, a poet’s poems being sung, lyrical and classy. Jazz was the kind of music he acquired a liking for from his ex-wife before things went sour between them. He kept their collection of recordings when she moved away, thinking he had gotten the better of the bargain.

He knew jazz was restless and wouldn’t stay put, but he liked its improvisation to stay within jazzy boundaries. Not like his ex-wife, whose restlessness knew no boundaries.

Approaching the windy deserted dark streets of Wood’s Hole, the detective let his GPS find Penzance Point Road and ten minutes later was pulling into the parking lot terraced into a hillside below the main building of the Kritalvanda Center for Yoga and Health. The Medical Examiner was outside the entrance doors, leaning against the yellow brick building, a cigarette dangling from his thick fingers.

“They didn’t even want me to have a smoke out here, Sam, they put up a stink about it,” he said, sullen.

“What happened in there?” asked Sam Fowler

“It was a 911 call. When the paramedics figured out what the problem was, they called Falmouth. They’ve got a couple of cars here, there’s me, and the paramedics are still here, too. They’re all parked around back, where the customers get checked in. That lot out front where you parked is where people leave their cars afterwards, for the day, or however long they’re here for.”

Throwing his butt to the side, he said, “Follow me, I know the way.”

Outside a second floor room a uniformed officer was waiting who showed them inside where two paramedics were lounging beside a gurney.

“It looks like his neck was broken and his breathing went haywire,” one of them explained as they stood over the corpse. “He died of respiratory failure, probably within five minutes.”

Sam Fowler glanced at the Medical Examiner.

“His name was John Cerberus. He was in charge of the exercise program here. I put his death at right around six o’clock. The class had just ended, and as I understand it, they all lay down, closed their eyes, and meditated for a few minutes. The teacher found him at about six-fifteen when she was closing the room. She’s the one who called. From the bruising on his neck I can say it was deliberate.”

“I thought it was hard to break someone’s neck,” said Sam Fowler.

“Despite what you see in the action movies, it’s almost impossible to break someone’s neck like this,” answered the Medical Examiner. “You have to be fast and apply a lot of torque to do it. You have to know exactly what you’re doing.”

“Wouldn’t someone have heard his neck breaking?”

“Like I said, it’s not the movies, where you hear a cracking sound.”

“So no one saw anything or heard anything?”

“I don’t know. That’s your job.”

When John Cerberus was gone, strapped down and wheeled away on the stainless steel gurney, Sam Fowler thought to himself that it was a hell of a mess when someone was killed in a roomful of people in broad daylight and no one saw or heard anything.

He walked out to the uniformed policeman in the hallway.

“Let’s get everybody who was in this room back here,” he said, “and I want to see whoever is in charge of this place. Get a list of everybody registered here, and all the staff people, and let’s make sure they’re all still on the grounds. Find out if they have any closed circuit, especially of the road in and out, and the parking lot. I’ll set up for interviews in the cafeteria I saw downstairs. Tell someone to get the lights on and some coffee for me.”

Ten minutes later sitting at one end of a long table in the cafeteria, his notebook and a microcassette recorder in front of him, Sam Fowler listened unhappily as he was told his options were the center’s signature-style Chai Tea or Moroccan Mint.

Vera Nyberg sat on the upper mattress of her bunk bed in the corner of the nearly deserted dormitory room, her knees pulled to her chest, leaning back against the wall, slowly twirling between her fingers the wilting Bird’s-foot Trefoil she had found on John Cerberus.

Where had it come from? She knew what it was and what it meant in the language of flowers. It meant revenge. Hadn’t she seen it recently? Although it had been a mild autumn, the temperatures not falling below forty, yet, it was late in the year for it to still be blooming.

“I know I’ve seen this somewhere,” she said as much to herself as to Elizabeth Archer in the bunk below her.

“What is it?” asked Elizabeth, swinging her legs off the lower bunk and taking a step on the ladder, pulling herself up by the railing of the upper bunk.

Elizabeth Archer was at the center on a six-month internship from the Columbia Business School MBA program. Like Vera she was immersed in yoga, but unlike Vera, who described herself as “a yoga teacher, that’s all,” she was an entrepreneur in the making. After graduation she planned on crowdfunding and opening and finally franchising high-end yoga studios. Her internship was a step towards that goal.

“I didn’t really like John Cerberus, but for someone to kill him, I just don’t know,” said Vera, her voice trailing away.

The principle of non-violence was a golden rule of yoga. Would anyone have broken John Cerberus’s neck, she wondered, even if he deserved to have his neck wrung. But, someone in her room had done just that. She knew it was someone who had been in her class because if anyone had come in through the door during corpse pose she would have heard them.

Maybe not their footsteps, but the pneumatic door closer was creaky and needed oiling. It was noisy.

“I know what you mean,” said Elizabeth, pulling her unruly blonde hair away from her face with both hands. “He flushed Amazing Grace down the toilet, but if that’s why somebody killed him, I guess he didn’t deserve to die because of that.”

Two years earlier, amid accusations of sexual impropriety with female students, and financial irregularities with the company’s pension fund, John Cerberus, a former New York City bond trader and founder of Amazing Grace Yoga, had stepped aside as CEO of a business that licensed almost two thousand teachers teaching more than a half million people worldwide his form of trademarked postural yoga.

Since then his conglomerate had crumbled. Amazing Grace’s headquarters building in Austin, Texas, barely five years old, had been sold, its teachers moving on to other disciplines, and the brand name disgraced. But, John Cerberus had weathered the storm and resumed teaching as an independent instructor, and in the middle of the year had been hired by the center as its Asana Director, supervising the teachers and offerings of the posture classes.

“I think it was someone in my class,” said Vera. “I’m sure of it.”

“No, not someone in your class!” exclaimed Elizabeth.

The center had been nearly deserted the Friday after Thanksgiving. The weekend was expected to be busier, especially since events like ‘The Healing Power of Drumming and Chanting’ and ‘Chakra Cleansing’ had been added to the calendar in hopes of attracting non-traditional holiday goers, or even traditionalists in need of relief from too much turkey.

When she asked Pattabhi Jois about being a vegetarian as step towards being a good yoga teacher, he said, “Meat eating makes you stiff. You will not be able to breathe right.”

Only nineteen people had taken Vera Nyberg’s class in a room that could easily fit seventy-five. Four of them were couples come down on I-93 from Boston for the long weekend. Three were good-looking young men, long-time friends of hers who lived in Provincetown year-round. A few were volunteers who worked in Food Services for their room and board and lived in the dormitory, like her. The rest were day-pass men and women who had come separately, and the last was one of the masseuses in the Wellness Center, who had slipped in late, after the class had almost started.

“It’s freaky to think there was a killer practicing yoga and planning to murder somebody the whole time,” said Elizabeth. “Who could have been that intense, and that quiet? You were all in the room, somebody would have heard them moving around, wouldn’t they have?”

Vera thought about what Lizzie was saying. She had a capable memory, but in a yoga room her mindfulness was sharp. For her the real art of memory was the art of attention. She paid attention to every person in her classes, making sure she knew their names beforehand, any limitations they might have, and where they were in the room so she could check on them whenever she thought it necessary. She hadn’t heard any footsteps during corpse pose, of that she was sure. Vera would have opened her eyes to see why someone was leaving the class early.

Who was closest to John Cerberus during the class?

Her friends had been in the front, where she insisted they be so she could keep an eye on any monkey business. They had clowned around up to the moment class started, but were good afterwards. Everyone else had been loosely knit at the center of the room, John Cerberus on the edge flanked by one of the wives from Boston, and on his outside hip, partly screened from her, there had been someone else. For some reason she couldn’t place the person. Their mat had been in a shadow between two high hats and off-center from her field of vision.

Maybe if she drew a map of where all the mats were in the room, and who had been on them, she would be able to see who had been on the mat just outside of John Cerberus.

“Lizzie, do you have a legal pad?” asked Vera.

Sam Fowler, who had been joined by a young plainclothesman, used his hands to push himself away from the table, stretched his stiff as a board legs out, and looked up at the ceiling. His notebook was almost filled with his illegible handwriting.

“Who do we have left?” he asked Jeremy Kroon, the only man the Falmouth station had been able to find on a late Friday night to help him.

“Just the teacher,” Kroon answered, pushing black bangs off his forehead.

How the hell did he get through the academy? He looks like one of the Beatles, thought Sam Fowler.

It was nearing one in the morning. Sam could feel the cold seeping in through the windows. The weather forecast was for a storm blowing in by Saturday night, although how stormy it might be was anybody’s guess. What was certain was that winter was close, he realized, rubbing his knees. The bone structure of the landscape would soon be all there was.

“Go ask somebody to get her down here.”

He had interviewed everyone who had been in the class, so far, and the Director of Program Development, as well, who seemed to be in charge since both the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Operating officer were out of town visiting family for the holidays.

Denise O’Neill was frank about her dislike of John Cerberus, although she admitted his qualifications.

“He is, I mean, was, excuse me, one of the most knowledgeable and experienced yoga teachers in the world, which is what he was always telling everybody. Maybe he was, I don’t know, I’m sure he was.”

She looked sad and annoyed at the same time.

“He studied with Iyengar, and he was once on their board of directors, too” she added. “It doesn’t get any better than that.”

Sam Fowler didn’t know who she was talking about and let it pass. He assumed Iyengar was yoga brass of some kind.

“Either it was because somebody owed him a favor, or it was the notoriety, or just a second chance, that’s why he landed here. We were supposed to work together, but he seemed to think he was my boss, even though I’ve been here eight years,” she added.

She had been reading alone in her room before dinner when John Cerburus was murdered.

“What were you reading?” he asked her.

“I was reading ‘The Courage to Be You’,” she said.

When she drew a blank from the police detective, she explained, “It’s a woman’s guide to emotional strength and self-esteem.”

“I see,” said Sam Fowler.

When she was gone he said to Jeremy Kroon, “Well, we know she didn’t kill anybody.”

The young police detective agreed, although he wasn’t exactly sure why.

Both couples from Boston said they knew John Cerberus from a new-age California music and yoga festival called Wanderlust they had been to three years ago, and that he had been the reason they had come to the center for the weekend. John Cerberus had taught a workshop earlier in the day about Tantra, the second half of which had been scheduled for Saturday.

“Tantra was the philosophical base of his Amazing Grace Yoga, did you know?” said one of the women, an attractive brunette in her late-30s.

“Isn’t that about sex?” asked Sam Fowler.

“That’s what most people think, but it’s more than that,” she answered. “It’s about sexual practice with the intention of spiritual awakening, increasing power, and experiencing bliss through embodiment. It’s not an indulgent practice.

“Everybody said John cheated on his girlfriends, and lied to them, but that’s not what it was ever about,” she continued, leaning forward. “Tantra is about using yoga poses, deep breathing, and stimulating acts, including intercourse, to hasten rapturous bliss.”

“Oh, I see,” he said, tilting his head and pressing his lips together thoughtfully.

She had been the last of the four Boston natives to be interviewed, one at a time, all of them separately. After watching her sashay out of the cafeteria Jeremy Kroon turned to Sam Fowler and asked, “You don’t think they’re involved, either, do you?

“No, they didn’t kill anyone,” he said. “They’re Back Bay people. They wouldn’t know how to break a chicken’s neck even if their own lives depended on it.”

Vera Nyberg’s three friends from Provincetown were excited about the murder, but at the same time nonchalant about the death. They had been asked, sitting in the hallway outside the cafeteria, to come in one at a time, but when they burst in together, Sam Fowler decided there was less bother in talking to them all at once than one at a time.

Only one person had killed John Cerberus. He doubted it was these three hens.

They didn’t so much answer his questions about what they seen or heard as talk about John Cerberus.

“What was all the partying about?” one of them said. “I must have missed that limb of yoga. And what about stealing retirement money from your employees? Patanjali has to be rolling over in his grave.”

“He was always jet-setting to Burning Man and Wanderlust,” another explained.

“He was the P. T. Barnum of yoga, the center of the world, and that whole posse of his, the kirtan bands and wannabe gurus,” the third man chimed in.

“It was a different kind of yoga?” asked Sam Fowler.

No, it didn’t have anything to do with yoga, they said.

“The postures and classes were what you would expect, but that’s just a part of the practice,“ said the fittest of the three fit men. ”The rest of it, all the parts of it that really matter, he ignored or turned them into a gala ball all his own.”

But, they all impressed on him that no one deserved to be murdered, and insisted that violence was beyond the pale in the world of yoga, of which there were many parts.

“What kind of yoga do you do?”

“We do Bikram Yoga, where there’s 90 minutes of the same poses in a hot room that’s 105 or 110 degrees and humidity is steamed in.”

“If you get your hands on a suspect, let us know,” said the cleanest cut of the three neat men. “We’ll sweat the truth out of him!”

An operetta is simply a small and gay opera, thought Sam Fowler, as the trio left the cafeteria.

None of the employees, the kitchen staff nor the masseuse, or the day-passers, had seen or heard or knew anything. None of them had been involved in Amazing Grace Yoga, personally or professionally. They deplored but forgave John Cerberus’s indiscretions, as much as they knew of them, and repeated that no one who practiced yoga would have considered killing him, much less actually committing the crime.

Waiting for Vera Nyberg and looking over his casebook, something nagged at Sam Fowler, something that was missing. It was something one of them hadn’t said, he thought.

When Elizabeth Archer answered the knock on the door of their dormitory room, spying the Falmouth patrolman on the threshold, Vera Nyberg was ready. She had been busy at the writing table mapping the mats and their owners in the room that afternoon. She now knew who had been on John Cerberus’s outside hip, and she knew where she had seen the Birds-foot Trefoil earlier in the week, as well.

What she didn’t know was whether she was going to tell the policeman what she knew.

As Vera came into the cafeteria Sam Fowler looked her up and down. She was slim, he could tell, even though she was wearing baggy black cotton sweatpants and a zip-up hoodie. He put her in her early-30s. Her black hair was long, in a ponytail, her face angular, and her mouth wide. Her glasses were a vintage style, out of the 1950s. Her hands and feet were large. She was wearing flip-flops, her toenails painted a bright red.

He stood up, motioned her to the chair opposite him, and she sat down.

After getting her name and address in Boston, as well as her cell phone number, Sam Fowler asked, “When was the last time you saw John Cerberus alive?”

“When he lay down in dead man’s pose,” she answered.

”Did you know him?”

“Yes, he was my boss, more-or-less, he and Denise. But, I’m one of the work exchange teachers, and I was only here for the month, so we didn’t come into contact much.”

“Do you know of any reason anyone would want to kill him?”

“Not anyone I know, no.”

She remembered what Pattabhi Jois said, “One year, two year, ten years. No use. Whole life. Whole life a practice.” John Cerberus wouldn’t be practicing anymore. His days had come to an end. No one can say for sure that he will be living tomorrow. All of John Cerberus’s living had been suddenly stopped. We take care of our lives and Krishna takes care of our deaths, she thought.

“Could someone have come into the room from outside and attacked him?”

“I don’t think so. I would have heard them.”

“Do you think someone in the room killed him?”

“I’m not sure, but I think it had to be someone in the room, yes.”

“Do you know who that might be?”

“No, not really.”

She seemed to be hedging her bets, he thought, and made a note.

“Did you kill him?” he suddenly asked her.

“No, of course not!” exclaimed Vera, taken aback by the question. “I don’t believe in causing harm. It’s in the Yoga Sutras.”

That was it, realized Sam Fowler, that’s what hadn’t been said by someone that everyone else had said in one way or another, which was that no one who practiced yoga would kill anyone. Who was it that hadn’t said it? He was sure he would have it either in his notes or on tape.

“The Yoga what?” Sam Fowler asked Vera Nyberg.

“The Yoga Sutras,” she said. “They were written a long time ago, about two thousand years, maybe at the same time as the Bible. But they’re short, just a couple of hundred sayings. It’s a guidebook, not a how-to book. It’s about choosing your best ethical path.”

“Like the Ten Commandments?” he asked.

“No, not exactly,” she answered.

“The rule about non-violence isn’t a rule, exactly. It’s more about not causing unnecessary harm, which happens when you start to see the origins and effects of violence. My teacher used to say, “Yoga is not physical, very wrong. Yoga is an internal practice. The rest is just a circus.” He meant it was about awareness, about expanding your consciousness. An open heart is what yoga is about, and as your heart opens not harming begins to make all the sense in the world.”

“What if you were attacked? Or if someone you loved was being assaulted? What would you do then?”

“I would do what my teacher always told us to do when we asked him questions in class.”

“What was that?”

“You do!”

“I see.”

Yoga takes care of its own, in its own way, thought Sam Fowler. In the meantime, somewhere in his interview notes someone had neglected to recite the mantra of non-violence. He wasn’t sure it meant anything, but it was the only anomaly of the night, so far. It wouldn’t hurt to find out who it was and interview them again.

“Thank you Miss Nyberg,” said Sam Fowler.

He had made a point to look and had not seen a wedding ring on her hand when he looked.

“I may or may not need to talk to you again tomorrow. We’ll let you know.”

The two police detectives watched her walk out.

“What made you think she might have had anything to do with it?” asked Jeremy Kroon.

“I didn’t.”

Sam Fowler knew better than anyone that nobody could read his scrawled cramped notes. He would have to review his casebook himself. In the meantime, he needed coffee.

“I need coffee,” he said to Jeremy Kroon. “Your job is to find some. I like JoMamas, but I’ll take Dunkin or anything brewed hot you can find at this time of night. Then you can call it a day, find somewhere to sack out, and we’ll get back to it at eight.”

An hour later, coffee at hand, Sam Fowler settled into a comfortable lounge chair in the main lobby, a table lamp lit on the end table beside him, and cracked open his casebook. Twenty minutes later, nearing three o’clock in the morning, the coffee barely touched, he was asleep, the casebook haphazrd in his lap.

The only sounds in the empty lobby the rest of the night were his breathing, the forced air from the furnace, and the winter wind testing the windows.

Vera sat up on the edge of her bunk at six-thirty, almost a half-hour before sunrise. She had wondered about the murder of John Cerberus for a short time, lying in bed after talking to the detective, but let it go. She quickly fell asleep, believing the answer would come to her in the morning.

She slipped nimbly down the ladder. Elizabeth was snoring softly carelessly in the bottom bunk. Peeking through the window Vera saw the sky was white-gray. The wind was downstream, neither rain nor snow was falling, although it felt cold through the glass.

It seemed like the storm had so far skirted them.

In the hallway she made her way to the new Wellness Center. Few doors were kept locked at Kritalvanda and the Wellness Center’s entrance door was not one of them. Once inside she thumbed the rocker switch and turned the lights on. There were five massage rooms in a row down the left corridor. She pored over the first room, and a minute later the second room. It was in the fourth room that she found what she was looking for, an empty glass cylinder bud vase on a mission-style corner table at the far end of the masseuse table.

Retracing her steps she made her way back to the dormitory and shook Elizabeth awake. “Lizzie, you know everybody here. Where does Lola Donning stay?”

Elizabeth pushed a mop of sandy hair away from her face and rubbed her eyes.

“The massage therapist?”

“Yes.”

“She’s in the west wing, in one of the semi-private rooms, on the second floor, although I think she’s been rooming by herself since she got here last month. I’m sure it’s room eight. But, you know, yesterday was her last day here. She gave two week’s notice.”

When Vera Nyberg got to Lola Donning’s room she found the door ajar and the room empty. The bed was unmade and the wardrobe closet, when she looked inside, was bare. The bathroom was shorn of toiletries.

Lola Donning was gone.

Leaning on the sink Vera Nyberg looked at herself in the mirror. Her gaze sank to the basin. Where had Lola Donning found Bird’s-foot Trefoil for her bud vase, the unusual flower Vera had noticed one afternoon while getting a massage late last month? It wasn’t a flower that grew in woodlands, like those that surrounded the center on three sides. It was a forage plant, grown for pasture or hay. She might have found it on the front side of the grounds, facing Buzzard’s Bay, but most of the front side was either sloping grassland that was regularly mowed or the terraced parking lot.

Then, without hesitation, Vera Nyberg knew where Lola Donning must have found the flower. She hurried back to the dormitory to get her winter coat.

“Lizzie, the policeman is sleeping in the lobby. I‘m going out to the circle. This is what I want you to do, and then meet me out there as soon as you can with your car keys,” she said, shrugging into her coat. “Pack some clothes, too.”

Once outside she wrapped a wool muffler around her long neck. The sky was bulked up with thick clouds and the morning light was raw and milky. The whitecaps on Buzzard’s Bay were sluggish. At the bottom of the stairs she avoided the parking lot and cut through to the labyrinth on the knoll.

The center’s garden labyrinth was not a maze with multiple dead ends and designed to confuse. The labyrinth had one entrance and a winding path to the middle. Vera walked to the middle where she found Lola Donning standing in a thin jacket with her back to her.

People don’t notice whether it’s summer or winter when they’re unhappy, she thought, and waited for Lola to see her. She glanced at the bracelet watch on her left wrist. It was seven-thirty.

“I wasn’t sure if it was going to be you or the police,” Lola Donning finally said, turning to face Vera Nyberg. “When they didn’t say anything about the flower I thought maybe you had taken it.”

“Yes, I took it.”

“How did you know what it meant?”

“My mother was a landscape designer. She specialized in gardens.”

They stood quietly for a few minutes.

“My mother and I lived in New Mexico for a long time, where I grew up,” said Lola Donning. “They have labyrinths there, the Indians, you know. There’s one entrance, which is birth, and in the center is God. Sometimes it’s a family labyrinth, and in the middle of the circle is your original ancestor, and two continuous lines join the twelve joints, just like this one.”

She pointed to the center of the labyrinth.

“When most people hear of a labyrinth they think of a maze, but that’s not what they are. A maze is like a puzzle to be solved, lots of choices to be made, but with a labyrinth, there’s only one choice to be made, which is whether to enter it or not.”

The yoga teacher thought of what her teacher told her when she asked him for advice at the end of her training in Mysore. “Each morning wake up. Do as much yoga as you want. Maybe you eat, maybe you fast. Maybe you sleep indoors, maybe you sleep outdoors. The next morning, wake up, and do again. Practice yoga, and all is coming!”

Was it like the labyrinth Lola Donning was describing, the labyrinth that had brought the two of them together, where the only choice was whether to be in it or not? Or was it like a maze in which everyone was doomed to make choices and then be forever defined by the choices they made?

She thought Pattabhi Jois would probably say that there is only the life we live as an experience, not as a problem to be resolved, like mice in a maze, whatever the final end might be.

“That’s where my mom met John Cerberus, when she was teaching yoga. It was in Loving, outside of Carlsbad. She was one of the first teachers he recruited, and she was with him until the end, two years ago. She died on New Year’s Day, almost a year ago, in the house I was born in.”

“I’m so sorry. What happened?” asked Vera before she could stop herself, suddenly realizing as she asked that it must have had everything to do with John Cerberus.

“She killed herself.”

The two women stood in the bleak cold, the thin line of dawn on the horizon behind them a mute pinkish orange slash, the late November wind a cold draft at their ankles and necks.

“She died because of him. I’d been working here less than a couple of weeks, and I saw him in a hallway one day. I almost fell down. I couldn’t believe it. I never in my life thought I’d see him again. But there he was, smug in his yoga trappings, on top of the world again.

“I wrote him a letter, telling him I knew what he had done, although I didn’t tell him who I was, and then gave two weeks notice that same day.”

Vera Nyberg stretched the muffler up her neck and over her mouth and ears as the wind rose, starting to gust.

“My mom said their yoga was special, the kind they pioneered. She was excited, right from the beginning. The yoga was about aligning the body and the spirit. Everything was done on a personal level, what they called the heart level. That’s the way it was for years, him and my mom.

“But, then they started training teachers and writing manuals and organizing workshops. They invited him to the Yoga Journal conferences and he was a hit. He got big. They had to project his image on screens in the conference rooms, there were so many people wanting to be a part of it. You couldn’t even see him anymore.

“He put together a traveling show and started going to all the festivals, and then he flew to Europe, and Japan, and he got even bigger. My mom thought it was the two of them, but it wasn’t, not anymore, although she couldn’t see it for what it had become.

“Then he brought sex into it, what he called left-handed tantra. He formed a Wicca coven with some of his students, in secret, and some teachers, but my mom wasn’t a part of that, either. She wouldn’t have done it even if she had known. She wasn’t like that.

“When she found out he told her the coven was a battery for his yoga, the foundation of his charisma. He said he was using sex energy in a positive and sacred way, but she told him he was out of integrity, and everything ended between them. She still worked for the yoga, but she wasn’t doing well.

“After everything fell apart and it came out into the open, my mom was devastated. Every day it got worse and worse until it was all over. I wasn’t living at home, but we talked every day. I was worried about her, but she sounded all right, until one day when she didn’t take my calls. I kept getting her voice mail, so I drove from Phoenix to Loving. It took me all night.

“I found her in bed in the morning. She looked just like she was asleep. She didn’t even leave a note for me, just for him, blaming him for everything.”

When men make choices only God is blameless.

“I don’t know what happened,” Lola said. “I didn’t mean to. I planned it, I think, yesterday, my last day, but at the same time, I didn’t, it just happened. It was like somebody else was doing it, like I was watching myself and couldn’t stop, like a bad dream.”

Tears were in Lola Donning’s eyes, the silent language of grief. The wind was blowing the rain away, but just for the moment.

“Since I’m going to be sticking my neck out, I think we should leave this place,” said Vera. “I don’t think there’s anything else to be found here.”

In the lobby Sam Fowler woke up. Elizabeth Archer was standing to the side of him, her hand shaking his shoulder.

“What time is it?” he asked, wiping a crumb of dried saliva from a corner of his mouth.

“It’s seven fifty-five,” she said, stepping back

“I must have fallen asleep. I didn’t know I was so tired.” He straightened up in the chair. “Is there something I can do for you?”

“Yes, Vera and I are supposed to drive one of the employees, really, an ex-employee now, she gave notice two week’s ago, to Boston, to the train station. We were wondering if that was all right?”

“You’re the desk girl, at the reception desk?” he asked, trying to place her.

“Yes, but I don’t think of myself as the desk girl,” she said, her voice cool and reserved. “My name is Elizabeth Archer. I coordinate our arrivals and departures.“

Sam Fowler would have preferred to be standing, not sitting in an easy chair.

“I may want to talk to you and Vera again, but that can wait until you’re back, ” he said, still groggy, shrugging.

He watched her walk away towards the main doors, pulling on her coat. She went down the stairs, around the parking lot and to the labyrinth, where through the plate glass window Sam Fowler saw two women waiting. One of them was Vera Nyberg. They talked for a minute, leaning into the wind, and then walked to the far sidewalk that led to the rear of the main building.

He looked down at his lap. His casebook wasn’t there, nor was it or his Sony micro-cassette recorder on the end table next to his chair.

After he gotten down on his hands and knees and searched the floor ten and fifteen feet in all directions, and finally stood up alone in the lobby, he realized with a grim finality they were gone.

“Goddamn it,” he said under his breath.

Flipping through Jeremy Kroon’s notebook as they sat in the cafeteria twenty minutes later, Sam Fowler found it was filled with cryptic doodles, loose-limbed cartoons of some of the people they had talked to, and several versions of the paper and pencil game called hangman.

“I saw you were taking notes, and you had that back-up recorder, so I didn’t bother,” the chagrined Jeremy Kroon explained.

“All right,” snorted Sam Fowler.

“I’m going up to Wareham, check in at the station, and I’ll be back early this evening. Get everyone’s forwarding addresses, phone numbers, and they’re free to go. So far we have nothing, but there’s something I’m missing. I can put my finger on it, but I don’t know where it is, exactly.”

Sam Fowler relied on evidence he gathered at crime scenes to come to conclusions and knew that reconstructing everything he had seen and heard from memory was not only improbable, but also suspect. It would be like shining a flashlight from side to side in the dark. Only successful liars have great memories, and he wasn’t a great liar.

His SUV was still in the front lot where he had left it the night before, but on his way to it he changed course and walked to the labyrinth. Ginny Walther had said that labyrinths were for finding things, not for losing your way in dead ends. In the late November morning light it was a drab place, the flagstones slick with an icy rain. He found the middle of the labyrinth easily enough and stood looking down on Buzzard’s Bay.

He debated whether it was a labyrinth or a maze, and whether there was anything there for him. After a moment he turned to retrace his steps, but taking his first step the toe of his black oxford slid on a frozen clump of gnarled green and yellow. As he slipped a hard gust of wind hit him in the chest and he went head over heels onto his back.

He thumped on the ground, knocking the wind out of him. His diaphragm spasmed and he gasped for air, grunting involuntarily. His lungs would not inflate. He tried to relax, and when his lungs finally started working again he clambered to his knees, breathing in through his nose and out through his mouth. He looked down at what he had slipped on. It was a crushed flower shaped like a bird’s foot.

Elizabeth Archer was at the wheel of her Nissan Rogue, Lola Donning in the passenger seat, and Vera Nyberg in the rear seat as they left the Kritalvanda Yoga Center on their way to Boston. None of them noticed Sam Fowler gulping air and struggling to get off his back in the eye of the labyrinth.

Driving through Falmouth Vera Nyberg suddenly said, “Let’s stop here. There’s a JoMamas on the corner.”

As they were returning to the car with coffee, tea, and hot breakfast sandwiches, Elizabeth Archer paused and said to Vera, “Oh, wait, there’s that something I should do.”

She walked to the front of the coffee shop, pulled a spiral notebook out of her coat pocket, and began tearing the pages out and dropping them into the outdoor trash receptacle. When she was done she walked around to the back of the shop, and pulling microcassette tapes out of a small satchel one at a time crushed them beneath the heel of her zip boots. She tossed the tapes, the cassette recorder, and the bag into the dumpster, and walked back to the car.

They drove north on Route 28A to the Bourne Bridge, and then east on Trowbridge Road to the Sagamore Bridge, but instead of crossing the bridge and continuing on to Boston, Vera told Elizabeth to turn right onto Route 6.

“But, that will take us back on to the Cape,” she said.

“I know,” said Vera. “Lizzie, have you ever read ‘On the Road’?”

“No, what’s that?”

“It’s a book from the 1950s by Jack Kerouac, Anyway, in the book it’s about Sal Paradise, and he starts hitchhiking to California on Route 6, but someone tells him “there’s no traffic passes through 6.” It’s raining and he wants to go fast and have experiences, so he goes a different way. But, you know, it’s an old road, the kind where people used to have adventures, and it’s the longest road in the country. When you get to Provincetown there’s a sign that says ‘End of US 6, Provincetown to Long Beach, Coast to Coast.’”

“All right, but where are you going with this?” asked Elizabeth Archer.

“I think we should go to Provincetown instead of Boston. That policeman is no fool. He’s like my father, who was a policeman. He thinks we went to Boston. Only we know Lola’s with us. She can stay with my friends. They have a guest room that’s empty all winter and they can find work for her. She can start over. She can practice yoga there, get back on her feet. My friends are crazy for Bikram Yoga, you know, the hot room kind. They’re always asking me to try it. They even say Bikram has a slogan that if you do his yoga every day for thirty days it will change your life.”

The afternoon sun peeked through the clouds as they sped east towards the end of the Cape. Once, when she asked Pattabhi Jois where inner peace came from, he told her, “Without yoga, what use? You practice many years, then shanti is coming, no problem.”

“Would you like to do that?” Vera Nyberg asked Lola Donning.

“Yes, I would,” said Lola, twisting in her seat towards Vera.

“I woke up every morning wanting to break his neck, thinking revenge would be sweet, but it’s not. I thought revenge was justice. It’s not. I should have left it in the hands of karma to take care of him. I hate what I did. I feel like a worse person than he was. The best revenge would have been to be as much unlike him as possible.”

At Orleans they drove into and out of the traffic circle, towards Eastham, Truro, and finally Provincetown at the fist end of the Outer Cape.

“I’ve heard Provincetown in the dead of winter is cold, but maybe the yoga there will warm up my heart,” she said, turning to stare out the side window.

She wrapped her hands around the extra-large cup of JoMamas and took a long slow sip of her special blend holiday chai tea.

“We’ll all warm up in Provincetown,” said Vera, as Lizzie flicked on the headlights to light up the gloom on the road ahead of them.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“Captures the vibe of mid-century NYC, from stickball in the streets to the Mob on the make.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn. New York City, 1956. Jackson Pollack opens a can of worms. President Eisenhower on his way to the opening game of the World Series where a hit man waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication