By Ed Staskus

By 1984 many bands had strutted their stuff at the Richfield Coliseum. It was built for basketball and anything else that could be booked between games. Everybody called the venue the Palace on the Prairie. It was in Richfield, Ohio. The bands included Led Zeppelin in 1975, Bruce Springsteen and the E-Street Band in 1978, the Rolling Stones in 1981, and Queen in 1982. The Bee Gees drove girls to screaming, crying, and pleading in 1979.

Frank Sinatra opened the place with a show in October 1974. “The crisscross of lights, mirroring the animation of 21,000 stylish people packed from floor to roof, transformed the gray amphitheater in the hills of Richfield Township into a huge first-night bouquet of green and blue,” is how The Cleveland Plain Dealer splashed Old Blue Eye’s show across its front page. We called him Slacksey because, no matter what, his slacks were always neatly pressed. Roger Daltrey gone solo closed the doors and shut off the lights for good in 1994. His show drew fewer than 5,000 fans. Nobody wrote a word about it or how he was dressed. Over the years there were might have been a thousand musical events at the Richfield Coliseum.

Vann Halen opened for Black Sabbath in 1978 and came back as headliners in 1984. When they did, they had to sit on their hands waiting for ice to melt. Walt Disney’s Magic Kingdom on Ice had just skated out of the building. When Van Halen came to town it was the one and only time I saw the band and the one and only time I went to a show at the Richfield Coliseum.

It wasn’t that I didn’t go to rock ‘n roll shows. It was that the few I went to were closer to home, like at the Allen Theater, the Agora, and Engineer’s Hall, where it was standing room only. There were no seats. Downtown was nearby but Richfield was a long way for my long-suffering car. Besides, I was by necessity a Scrooge. Big shows charged big bucks. First things came first, like food and shelter.

I saw the Doors at the Allen Theater in 1970, the Clash at the Agora in 1979, and the Dead Kennedys at Engineer’s Hall in 1983. The Dead Kennedys blew into town during a heat wave. The air conditioning at the Engineer’s Hall was non-existent and there were no windows. Everybody sweated up a storm and everybody stayed through the encore. Six years later the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers sold their building. It was demolished and replaced by a posh hotel. The Dead Kennedys never came back.

The Doors opened their sold-out Friday night show in 1970 with ‘Roadhouse Blues’ followed by ‘Break on Through’ and ‘Backdoor Man’. They covered Bo Diddley’s ‘Who Do You Love?’ That was a surprise. “I walk 47 miles of barbed wire, I use a cobra snake for a necktie, I got a brand new house on the roadside, made from rattlesnake hide.” They sounded much better live than on carefully managed vinyl. They were more than worth the six dollars for my orchestra seat ticket. My girlfriend paid her own way. We had an even-steven relationship. Eli Radish, a local band, opened, and were funky and fun, but all through their set everybody was antsy waiting for Jim Morrison.

“He worked the crowd with his staring sneers and sexy leather posing, witch doctor mumbling and slouching about,” said Jim Brite, who was in the crowd. “The lighting and sound were dramatic. The band was great, with extended solos and workmanlike professionalism, delivering the music behind the shaman. No one could take their eyes off Jim. It was one of the best concerts I ever saw and I’ll never forget it.”

The Doors were banned in Miami for Jim Morrison’s obscene language and lewd behavior. He told the city fathers to call him the Lizard King. They had been banned from performing in Cincinnati and Dayton the year before. None of it mattered to the 3,000 of us filling every seat at the Allen Theater.

“Jim Morrison swigged beer and smiled a lot between numbers,” Dick Wooten wrote in The Cleveland Press the nest day. “When he performs, he closes his eyes, cups his hand over his right ear, and clutches the mike. His voice is pleasant, but his style also involves shouts and screams that hammer your nervous system.”

When it was over we whistled, roared, and clapped until the house lights came on. We were disappointed there was no encore. Everybody was getting to their feet when Jim Morrison suddenly came back on stage. “Somebody stole my leather jacket, he bellowed. “Thanks a lot Cleveland!” He flipped us the finger. Then he said, “Nobody leaves until I get it back!” Nobody knew what to do. A half-dozen rough-looking bikers jogged to the back of the hall and blocked the doors. When my girlfriend and I looked to the side for another way out, Jim Morrison had left the stage, but then a minute later came back.

“Sorry, that was a mistake. I found my jacket.”

He said the band wanted to play some more songs to make up for the mistake, but that John Densmore’s hands were messed up. He was the group’s drummer. The beat couldn’t go on without a beat, except it could and did.

“John their drummer was walking around backstage and holding up his hands which seemed bloody in the creases of his fingers,” said Skip Heil, the drummer for Eli Radish. “I felt all warmed up since we played before them, so I said I’ll do it. I wasn’t sure of the songs, but I thought they were simple shuffles.”

After two encores, and telling everybody how much he loved Cleveland, Jim Morrison accidentally locked himself in an old bathroom backstage. One of the band’s roadies said, “Stand back Jim.” He knocked the door down and set him free.

The band toured non-stop after they left Cleveland. They had been touring non-stop for several years. Jim Morrison died in Paris of a heroin overdose the next year and the door shut forever on the band. It was a shame.

The Richfield Coliseum was an arena in the middle of nowhere, halfway between Akron and Cleveland. It was built to be the home of the Cleveland Cavaliers, the local NBA team, although indoor soccer, indoor football, and hockey were played there, too. Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics said it was his favorite place to shoot hoops. He played his last pro game there. Muhammed Ali fought Chuck Wepner there in 1975. Dave Jones, Ali’s nutritionist, could never get the boxer to try soy burgers. He had to have his red meat. Chuck Wepner was his red meat that night. There were rodeos and monster trucks. There were high wire acts and hallelujah choruses. The WWF Survivor Series came and went and came back.

I had a friend who had gotten free tickets to see Van Halen. Two other friends of ours went with us but had to fork over $10.75 apiece for the privilege. I didn’t know much about the band, except that they were no doubt about it loud as two or three jet engines, but free is free and since I had the free time I went.

The headbangers were from Pasadena California. They were Eddie Van Halen on guitar, Eddie’s brother Alex Van Halen on drums, Mike Anthony on bass, and David Lee Roth belting it out up front. Mike Anthony sang back-up while keeping the low pitch going.

“It wasn’t until the fourth or fifth Van Halen record that people would go, ‘Wow! You’re singing backgrounds on those records. We thought it was David Lee Roth doing that, too,’” the bass player said. “And I go, Hell, no! That’s not David Lee Roth.”

The word among aficionado’s was that the band was “restoring hard rock to the forefront of the music scene,” whatever that meant. I was listening to lots of John Lee Hooker and the Balfa Brothers. The rock ‘n roll parade was largely passing me by. I didn’t have a clue who was at the front of the parade.

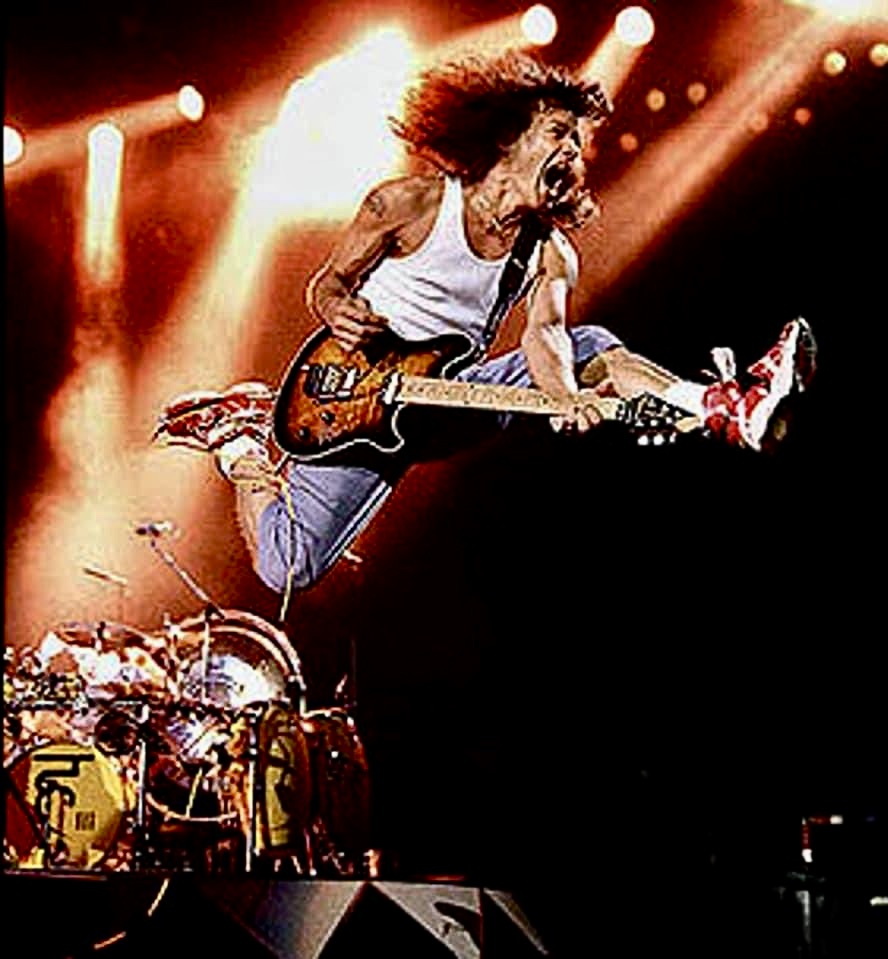

Everybody I asked said Van Halen’s live shows were crazy energetic and Eddie Van Halen was a crazy virtuoso on the electric guitar. During the show he switched guitars right and left, but more-or-less stuck to a Stratocaster, except it wasn’t exactly a Stratocaster. Eddie Van Halen called it a Frankenstrat.

“I wanted a Fender vibrato and a Stratocaster body style with a humbucker in it, and it did not exist,” he said. “People looked at me like I was crazy when I said that’s what I want. Where could I go to have someone make me one? Well, no one would, so I built one myself.” He wasn’t trying to find himself. He was creating himself.

His homemade six-string was almost ten years old in 1984, made of odds and ends, a two-piece maple neck stuck onto a Stratocaster-style body. He used a chisel to gouge a hole in the body where he stuck a humbucking pickup taken out of a 1958 Gibson. He used black electrical tape to wrap up the loose ends and a can of red spray paint to get the look he wanted. When he met Kramer Guitar boss Dennis Berardi in 1982 Eddie showed him his Frankenstrat. It was his prize possession.

“We went up to his house and he got it out,” Dennis said. “It looked like something you’d throw in the garbage. That was his famous guitar.”

Van Halen released their first LP in 1978. By 1982 they had released four more LP’s. When they came to northeast Ohio they were one of the most successful rock acts of the day, if not the most successful. Their album “1984” sold 10 million copies and generated four hit singles. “Jump” jumped the charts to become a number one single.

When the lights went down and the stage lights went up, the band took their spots. Eddie Van Halen wore tiger striped camo pants and a matching open jacket over no shirt. He wore a white bandana and his hair long. Mike Anthony wore a dark short-sleeved shirt and red pants. He wore his hair long, too. David Lee Roth wore a sleeveless vest, leather pants ripped and stitched every which way, and hula hoop bracelets on his wrists. He wore his hair even longer. Alex Van Halen wore a headband. The headband was all I could see of him behind his Wall of Drums. There were speakers galore stacked on top of each other on both sides of the drum set.

When they launched into “Running with the Devil” Mike Anthony ran across the stage and slid on his knees playing the opening notes. David Lee Roth was a wild man, swinging a sword around like Zorro and doing acrobatics like the Olympian Kurt Thomas. He did Radio City Rockette kicks and jumped over the drum set while singing “Jump.”

Taylor Swift would have flipped out if she had been alive, but she wasn’t going to be alive for another five years. When she came into her own years later she got very good at strutting on stage, but she never jumped a drum set. The audience at the Palace on the Prairie was alive as they were ever going to be that night. David Lee Roth’s high flying got a standing ovation.

In the middle of one song, David Lee Roth stopped singing. The band played on but slowly dropped out, one instrument at a time. “I say fuck the show, let’s all go across the street and get drunk,” he shouted into his handheld microphone. The crowd hooted, hollered, and cheered, forgetting for a moment they were in the middle of nowhere and the closest bar was miles away.

One of the best parts of the show was when Alex Van Halen and Mike Anthony did a long bass and drum duet. Eddie Van Halen did some good work on keyboards, doing the opener for “I’ll Wait.” He did his best work, however, on his guitars. He had a way of playing with two hands on the fretboard. He learned it from Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin.

“I think I got the idea of tapping by watching him do his “Heartbreaker” solo back in 1971. He was doing a pull-off to an open string, and I thought wait a minute, open string and pull off? I can do that, but what if I use my finger as the nut and move it around? I just kind of took it and ran with it.” He filed for and got a patent for a device that attaches to the back of an electric guitar. It allows the musician to employ the tapping technique by playing the guitar like a piano with the face upward instead of forward.

Most of us stayed in our seats during most of the show, only coming to our feet to applaud, but there was an undulating crowd squished like sardines at the front of the stage, where they stayed from beginning to end. They never left their feet. It was more than loud enough where we were up near the rafters. It had to be deafening if not mind-blowing being at the lip of the speakers.

By the time the show ended Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth had long since stripped off their shirts. They came back for several encores and then the music was over. It took a half hour to shuffle out of the arena, a half hour to find our car, and another half hour to inch along the traffic jam the half mile to the highway. My sense hearing came back somewhere along I-271 on the way home.

After the concert I went back to listening to the blues and zydeco. I didn’t rush out to buy any records by Van Halen. My cat and the neighbors, not to mention my peace and quiet roommate, would have complained about the noise. I tried explaining to my cat that one man’s noise was another man’s symphony, but he wasn’t having any of it.

Six years later, after the excitement of being pushed and pulled into existence had died down, when Taylor Swift was in her crib in the living room, she took a peek at a film clip on MTV of the 1984 Van Halen concert at the Richfield Coliseum. She went bananas over the sold-out crowd. She made a vow then and there that she would do the sure thing. She wasn’t going to invite 20,000 fans to hit the bottle. She was going to schmooze them into buying the bottle for her.

The first thing she would do when she was ready to sing her way to stardom was head to Nashville. It would be a baby step, but she had her sights set. It was going to be the hillbilly highway first and then the superhighway. Her father was a stockbroker at Merrill Lynch and her mother was a marketing manager at an advertising agency. She already knew the way to the teller’s window at the bank. She was determined to be a rich girl when she was grown up.

She was sure as shooting not going to strum a Frankenstrat or bust out any freaky Mighty Mouse moves, with or without a sword, with or without a shirt, although her legs were fair game. They were shapely legs made for boots that were made for walking. She was going to belt out her break-up ballads and march her way to the front of the hit parade. She was going to blend Frank Sinatra’s pressed pants with some tried-and-true country, add a dash of spicy pop, mix in lots of love and heartache, and deliver it with catchy melodies.

Van Halen’s aim during their time at the top of the charts seemed to be to die of exhaustion rather than boredom. Their aim was true. Taylor Swift’s aim was different. She was going to the top of the charts but she wasn’t going to die of exhaustion getting there. She wasn’t going to take any chances, no matter how boring it might be.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“Captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn, New York City, 1956. Stickball in the streets and the Mob on the make. President Eisenhower on his way to Ebbets Field for the opening game of the World Series. A killer waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication