By Ed Staskus

When the Juventus Folk Dance Festival showed up towards the end of June, I didn’t brush off my dancing shoes or brush up on my steps. I never had many steps to begin with, even though I had once been in the game. I had done some stepping with a minor league folk dancing group who practiced at the Lithuanian Catholic church in North Collinwood, near where my family lived. I grew up in a household with one bathroom which everybody wanted to use at the same time in the morning. I picked up most of my ad lib two-steps waiting for my turn. In the end, which wasn’t long coming, I was kicked out of the minor league group. Being clumsy isn’t especially a problem bunny hopping by yourself, but it can be in a group of twenty-or-more in close quarters going in circles and branching out in all directions.

Something on the order of three hundred dancers from five countries cut the rug at the show in the Berkman Hall Auditorium on the campus of Cleveland State University. “They represent every region of Lithuania,” said Ingrida Bublys, the Honorary Consul of Lithuania for Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. The event was sold-out and sponsored by the dance group known as Svyturys, which means Beacon. The Beacon has been lighting the way in Cleveland for twenty years.

Although Lithuania has been around for ages, Lithuanian folk dancing has only been around for an age. It got started in the late nineteenth century during the National Awakening, when the country was under the thumb of Moscow. The native language and native writing were proscribed, but the Czar turned a blind eye to busting moves, so long as the busting didn’t have anything to do with treason and dynamite. The first Lithuanian folk dance, known as Suktinis, was performed in St. Petersburg in 1903. Suktinis means winding or twisting. The first down home dance festival was held in Kaunas, then the capital of the country, in 1937. There were 448 dancers hoofing it, most of them going around and around.

Lithuanian folk dances are usually one of two kinds. There are sokiai, which are ordinary dances, and there are rateliai, which are ring dances. Sokiai are often accompanied by instrumental music and sometimes by songs. One of the most popular dances is called Malunelis, which means windmill. Ring dances are more-or-less walked, sometimes slowly, sometimes faster, sometimes in a slow trot. The secret is in the center of the ring for anybody who knows where to look. The movements are simple and usually repeated over and over. They take the form of circles and double circles, as well as rows, bridges, and chains. The circles transform into lines and snakes as the dancing progresses. The dancers sometimes break up into pairs. The high stepping that follows is usually of foreign origin, like the Polish polka.

Raganaites, which means the Dance of the Little Witches, is performed by young girls wielding straw brooms. They pretend to ride them. They twirl them, do some mock jousting with them, and try not to poke anybody’s eye out. A witch taking time off from her cauldron must be at least a hundred years old and have memorized the 7,892 spells in the Great Book of Magic before being allowed to do the dance. But the rules are always waived for Lithuanian kids.

If an honest-to-goodness witch ever threatened me by saying she planned on dancing on my grave, I would tell her, “Be my guest. Even though I’m the grandson of landed farmers, I plan on being buried at sea.”

Before there was Svyturys there was Grandinele, which means Little Chain, and before there was Grandinele there were six refugees who in 1948 performed at the Slovak Cultural Gardens. It was One World Day. Nearly 40,000 Lithuanians landed in the United States after World War Two. Four thousand of them landed in Cleveland, joining the 10,000-some who already lived in the northern Ohio city. Even though the Lithuanian Cultural Garden was officially dedicated in 1936, the garden was only big enough on its lower level to hold the bust of Jonas Basanavicius, a freedom fighter who never gave up fighting tyranny. Over time a middle and upper level were created. The upper level is where the Fountain of Birute is. She was a priestess in the Temple of the God of Thunder. In her day the Russians stayed away from the Baltics. Even the Golden Horde was known to warn freebooters, “Beware the Lithuanians.” The Grand Dukes weren’t anybody the Russians wanted to mess with. They kept to their dachas, which were dry except for cupboards full of vodka. There were lightning rods on the roofs.

My sister Rita was a dancer in Grandinele, the by-then acclaimed folk dancing group, in the mid-1970s. My brother Rick was not in any dancing group. He was smooth with the spoken word, but had two left feet like me, except I could tell my two feet apart, while he couldn’t. He was banned for fear of kicking up his heels in too many directions. Rita danced in Grandinele for almost five years. During that time, she toured Argentina, France, and Germany with the group. “We danced in front of large audiences,” she said. “Before I went I had no idea there were so many Lithuanians in South America.” The group wasn’t allowed to perform in Lithuania, which was behind the Iron Curtain at the time. The Kremlin didn’t let anybody beat feet in Eastern Europe.

Grandinele was formed by Luidas and Alexandra Sagys in 1953. The dancers were mostly high school and college students. They rehearsed twice a week at a YMCA in Cleveland Heights. A second group composed of tadpoles was formed in 1973, to teach them the basics and get them ready for the limelight. They didn’t perform in front of the public, but they performed in front of Luidas and Alexandra, which could be even more unnerving.

“He was strict but creative,” Rita said. “Not everybody in the community liked him making up his own folk dances, which were almost like ballets with a story. She was strict and could be mean.” Alexandra was the group’s business manager. She took care of the costumes. Nobody wanted to get on the wrong side of her, unless they wanted to risk being dressed up like Raggedy Ann.

Luidas Sagys had been a professional dancer with the National Folk Dance Ensemble in Lithuania before World War Two. He fled the country after the Red Army came back in 1944. They seemed to always be coming back, even though the Baltics were sick of them. The apparatchik’s thought Lithuania was theirs to do with as they pleased. Their revolutionary ideals were long gone and not coming back. They had turned into rats. Their reasoning was that since the Nemunas River rises in central Belarus and flows through Lithuania, it was Russian water and wherever it went the land was part of Mother Russia. They have applied the same reasoning to the flow of the Dnieper River, which rises near Smolensk before flowing through Ukraine to the Black Sea. Ukraine is still living with the consequences of Moscow’s crazy reasoning.

When Luidas Sagys formed Grandinele he could shake a leg with the best of them. In 1963 he directed the Second American and Canadian Folk Dance Festival. He looked authentic as could be whenever he donned indigenous garb and got into the act. Even though his culture and imagination were the genesis of his art, the art of him was his body in motion for all to see. He ran the Folk Dance Festival in Cleveland for many years. He liked to wear bow ties and sported a puckish grin when he wasn’t working on new choreography. When he was done, he liked to have a drink or two.

My wife and I were by chance in Toronto when the XI North American Lithuanian Folk Dance Festival was staged there in 2000. The quadrennial festival, known as the Sokiu Svente, which means Dancing Celebration, was first staged in Chicago in 1957. We found tickets at the last minute and hurriedly got our bottoms in place. We sat in the cheap seats of the big auditorium. We didn’t mind since the view was better, anyway. Zilvitis, a musical ensemble from Lithuania, accompanied the performance of 1,600 dancers.

The show was a swirl of color and action. A couple of thousand dancers dressed in the red, green, and yellow colors of Lithuania is a lot to look at in the space of a few hours, not to mention the mass maneuvering and the music. The performers and jam-packed audience were more Lithuanians than I had ever seen in one place. On top of that most of them were speaking the natal tongue. I grew up with the lingo and was able to keep up.

One of the dance groups at the show was Malunas, which means to mill. Back in the day, before they did much dancing, most Lithuanians were either peasants or farmers. There were grindstones far and wide. Baltimore was the dance group’s homestead. They had been performing up and down the East Coast for nearly thirty years. They have appeared on PBS-TV and at presidential inauguration festivities. Toronto was their fifth Sokiu Sevente.

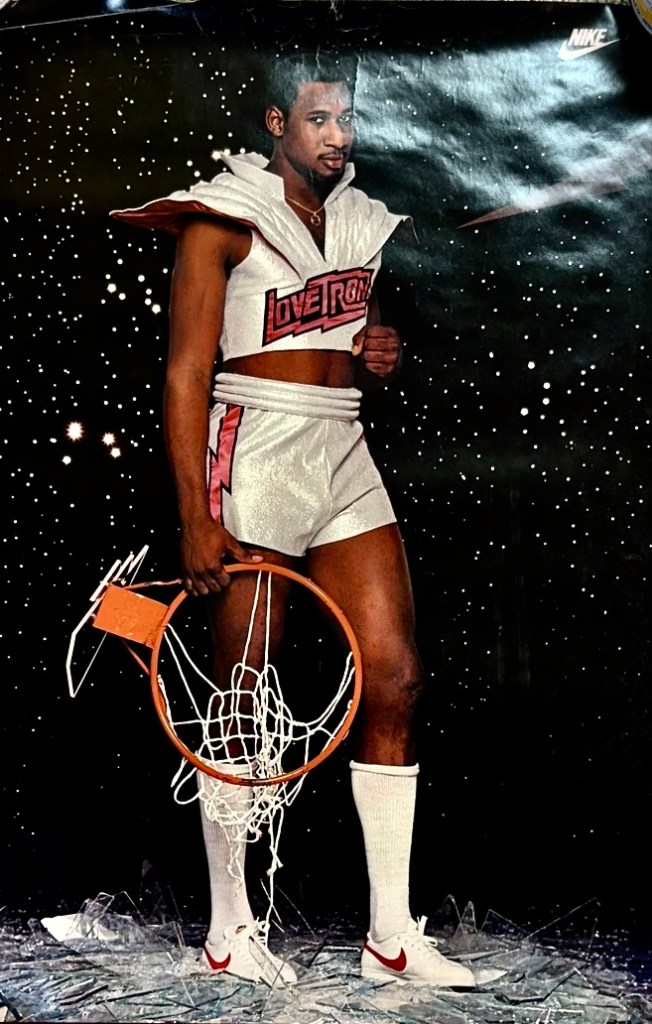

A tradition at every Sokiu Svente during the rehearsal before the big show is for every group to wear a distinguishing practice outfit. When silk-screened t-shirts became popular in the 1970s, groups began to design and wear custom t-shirts. They came up with their own silk-screened identities. After the last practice groups trade identities, which become mementoes. In Toronto, Malunas came up with a new idea. They were inspired by the Grateful Dead shirts of the 1992 and 1996 Lithuanian Olympic Basketball teams. One of their own, Michelle Dulys, dreamed up a design of skeletons as dancers rather than basketball players. The t-shirts were a knockout. The ones not exchanged were sold fast, faster than we could buy one. We watched the last skeleton sauntering off from the concession stand.

The Lithuanian Folk Dance Festival Institute was formed soon after the Sokiu Svente became a going concern to liaison with dance groups worldwide. The institute hosts a week-long training course at Camp Dainava, in southeastern Michigan. Although it is an educational, recreational, and cultural summer camp for children and young adults, the name of the camp derives either from the past tense of the word sing, from a village in the middle of nowhere back in the homeland, or from a Lithuanian liqueur of the same name, made with grain spirits and fruit juices. The booze has a vibrant red color and a complex, sour-like flavor. Even though Lithuanians are ranked among the top ten barflies in the world, it is forbidden on all 226 acres of the campground.

The two-and-a-half-hour divertissement that was the Juventas Festival started with a parade and a song. There was some speech-making. There was a violin, a couple of wind instruments, and a drummer, while an accordion led the way. There were costumes galore and faux torches. There was circle dancing. There was pairs dancing. The pairs dancing got fast and lively. There was more singing. Before every part of the show a young man and a young woman in civilian clothes explained, in both English and Lithuanian, what was coming up. A group of kids did their own version of a circle dance. Not one of them got dizzy and fell over. There was a courtship dance, the young men and women taking their wooden shoes off and going at the romance barefoot. Whenever the top guns came back, everybody sat up. They were good as gold. They had it going.

In the end all the dancers somehow squeezed themselves onto all the parts of the stage. There was waving and rhythmic clapping. There were loads of smiles. A half dozen men lifted a half dozen women up on their shoulders and did an impromptu circle dance. It was a wrap.

Most of June in Cleveland had been dry, so much so that lawns were going yellow. But it had rained a few days earlier. The smoke from the Canadian forest fires that had made the sky hazy gray for more than a week had gone somewhere else. Driving home everything smelled fresh and clean. The dancing had been traditional but not hidebound. It had been fresh and alive.

Life can often be more like wrestling than dancing. Many people believe living has meaning only in the struggle. That’s just the way things are. But nobody can wrestle all day and all night. “The one thing that can solve most of our problems is dancing,” said James Brown, the boogaloo man known as Soul Brother No. 1. What he didn’t say was that, in a way, it’s like going to church. Nobody bends a knee in the sanctuary to find trouble. They go there and the dance hall to lose it.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Late summer, New York City, 1956. The Mob on the make and the streets full of menace. President Eisenhower on his way to Brooklyn for the opening game of the World Series. A killer waits in the wings. Stan Riddman, a private eye working out of Hell’s Kitchen, scares up the shadows looking for a straight answer.

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication