By Ed Staskus

When Mary Smith picks up a fiddle, she’s got about twenty years of life with it behind her. When she picks up a guitar, she’s got about seventy years behind her. When she plays the mandolin, organ, or piano, it’s anybody’s guess.

“We always had music at home,” she said. “My dad played mouth organ and step danced. When I was growing up there was no TV, so the thing to do was have house parties.”

Home was the North Rustico lighthouse on the north-central shore of Prince Edward Island, and later a house her father, George Pineau, built up the road on Harbourview Drive. George and his wife Ruby rolled up the oilcloth on weekends. The kids were sent to bed.

“They would have three or four couples come over, cook up a big feed of salt fish and potatoes, and play music,” said Mary. Her father would dance jigs and play ‘George’s Tune’ on his harmonica.

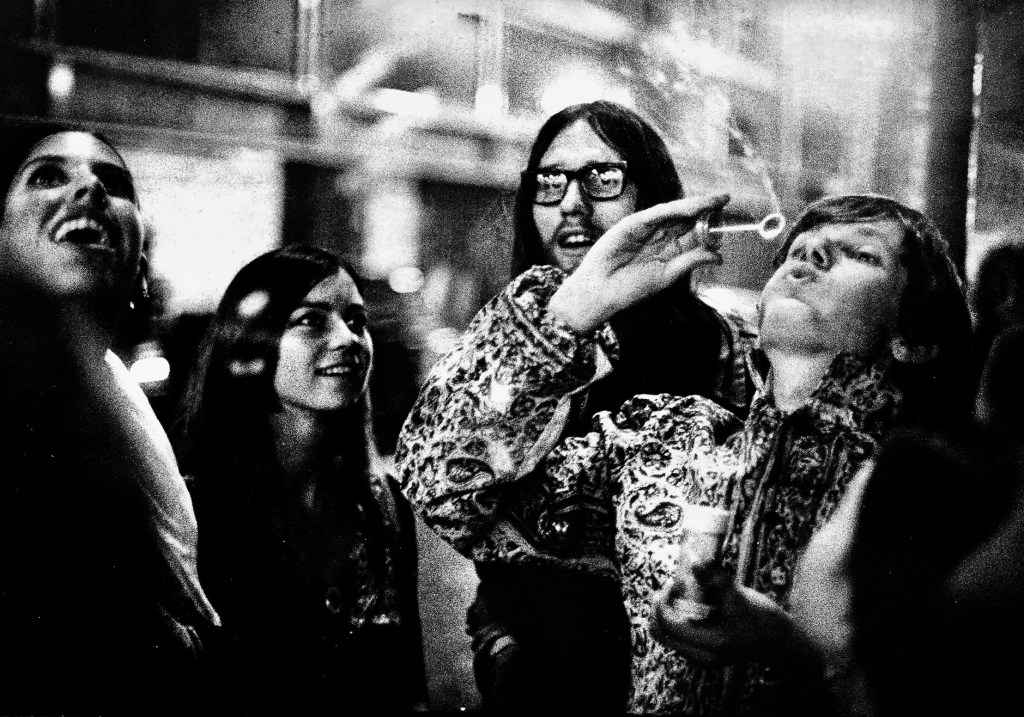

“On winter nights it was the custom in villages for friends to collect in a kitchen and hold a ceilidh,” explained Joe Riley, who designs and installs kitchens in the surrounding area. “They sang old or new songs set to old music or new music composed in the manner of the old, and maybe a few lies would be shared among friends.”

“We used to sneak down the stairs. I always wanted to be a part of it,” Mary said. “I thought, if I can get a guitar, and learn to play it, I could stay up and play for them. My dad wanted me to play a fiddle, but I wouldn’t bother with it. I kept asking for a guitar and eventually he ordered one.”

It came from Sears, Roebuck & Co. It was a Gene Autry Round-up guitar. Gene Autry was a rodeo performer and crooner. He was “The Singing Cowboy” in the movies. His name was inscribed on the guitar. A cowboy riding herd and swinging a lariat above his head was stencil-painted on the front. She still has it, although it’s not part of her gear on the road.

“I learned how to play a few chords.”

Square dancing was popular in her neck of the woods, and even though there were several good fiddlers, there were no guitar players. As she became more accomplished on her Round-up, she began accompanying fiddlers at local dances.

The North Rustico lighthouse was her home when she was a child. Although not many children are born at home, it was where she was born. She didn’t go far that first day, tired out by the move, and slept the rest of the day.

Only about 1% of babies today are delivered outside of a hospital. Until the 20th century most women gave birth at home. When someone was ready to go, her friends and relatives and a midwife would help. As late as 1900 about half of all babies were still brought into the world by midwives. By the 1930s, however, after the advent of anesthesia, only one of ten were delivered by them.

Not many were delivered by a neighbor, like Mary. “There was nobody else around. If you stayed home to have a baby, somebody had to help out.”

The lighthouse was built in 1876 on the North Rustico beach, a pyramidal white wooden tower and attached living space. Eight years later it was moved to the entrance of the harbor. George Pineau was the keeper of the lighthouse from 1925 until 1960, when the beam was automated.

“My grandfather was lighthouse keeper for many years, and my father was the keeper for thirty four years. I lived in the lighthouse until I was eight years old.”

Mary grew up on the harbor road, where she has moved back to and lives to this day, as a child running the mile-or-so up and down the road from one end to the other with her brother and sister. Fish factories canned lobster and salt fish, shipping it to the United States and West Indies. Fish peddlers loaded horse-drawn wagons and small trucks, selling cod, herring, and mackerel door-to-door.

A three-story hotel stood on the rise across the street from the present-day Blue Mussel Café.

“My Aunt Angie bought it, tore it down, and built a house with the lumber. My dad was laid back, but his twin sister was a fiery person.” Her father was a fisherman, working hard, but enough of a go-with-the-flow man to be able to live to one hundred and three before he was laid to rest.

In the summer Mary fished for smelt and sold them for a penny a dozen to tourists. When she had a pocketful of pennies she ran to the grocery store on Route 6. “You could buy a lot of candy for three or four cents.”

There were two schools serving the community, one Protestant and one Catholic. “In them days the Protestant and Catholic relationship wasn’t great.” When the Stella Maris school in North Rustico burned down in the early 1950s, classes were organized in the church until the school was rebuilt.

“I was in grade ten when I quit. You can’t quit now, but we went to work early back then.”

Many secondary students dropped out of school. There were plenty of entry-level jobs in agriculture and the fisheries. As late as 1990 the dropout rate on Prince Edward Island was 20%. Today, it is 6%.

She moved to Ontario, worked, came back to Prince Edward Island, met her husband-to-be, Al Smith, a Nova Scotian who was seasonal fishing out of the town harbor, and they got married when she was eighteen years old.

When they had a son and made a home, at the far end of the harbor mouth, it was in North Rustico. “We had a deep-sea fishing business.” Fishing, along with farming and tourism, drive the economy on the island. Shellfish like mussels and lobsters are the mainstay. Mary kept house, raised their son, and lent a hand with the gear. She mended nets, repaired pots, and rafted trap muzzles. She mixed their own cement runners for weights to sink the pots.

“The twine in the traps, what we called the hedge, we used to knit all those by hand. Nowadays they buy all the stuff.”

She stayed on shore more often than not. She was prone to seasickness, a disturbance of the inner ear. It especially wreaks havoc with balance. Christopher Columbus and Lord Nelson both suffered from it.

One day, just as that year’s fishing season was about to start, Al Smith’s hired man told him he was moving west in search of better prospects. He would have to look for another helpmate right away. “Well, Mary would never go because she gets seasick,” said one of their neighbors. That evening she told her husband, “I guess I’m going fishing in the spring.”

“Oh, God, it’ll be too hard for you,” Al said.

“There’s no women fishing in Rustico, and they say I can’t do it, so I’m going to go,” said Mary said. She shortly became the fishing fleet’s first girl Friday.

There are several ways of battling motion sickness. Cast off well-rested, well-nourished, and sober. Insert an ear plug in one ear. Keep your eyes on the horizon. Riding it out is sometimes the only remedy.

“I couldn’t physically lift the traps, they were too heavy, but I could slide them. My husband would haul them up and push the trap to me. I would take the lobster out and rebait the trap, slide it down the washboard to the back with the movement of the boat, and kick it off. There was rope all over, so you had to watch where your feet were, because there’s fathoms of rope and it’s going over fast.

“On a nice morning, going out to work, the sun coming up, we would look back and see the green and red of Prince Edward Island. It was beautiful. It was good work.”

Al and Mary Smith fished together for four years. They fished for lobster, mackerel, cod, and tuna. “It took me four years to get over being seasick,” she said. A sure cure is sitting down under your own roof on dry land four years later.

When her work on the water was done, she cast about for another kind of work.

“I always loved to draw,” she said. “So, when I wasn’t fishing anymore, and our son was grown up, I talked to my husband about it.”

“Why don’t you take a course?” Al said.

“Someday I’ll do that,” Mary daid

Someday came sooner than later and she enrolled in a two-year commercial design course at Holland College in Charlottetown, the provincial capital. The community college is named after British Army surveyor Captain Samuel Holland, offers more than one hundred and fifty degree pathways, and more than 90% of its graduates find employment.

Two years later, art degree in hand, she decided she wanted to teach art. She thought, I’ll go to the University of Prince Edward Island and get a teacher’s license. She went to see the Dean of Education at UPEI.

“What education do you have?” asked Roy Campbell, who was the dean.

“I only have grade ten.”

“Well,” he said.

She had brought a long list of courses she was interested in taking. He looked at the list. “Well,” he said, “you should be realistic. I suggest you not take more than three courses at any one time.”

“That was kind of insulting. He thinks I probably can’t even do three. I’ll show him. I’ll take six. Oh, my God, that was a mistake. It was a hectic time.”

It got more hectic her second year, when she entered the world of higher level courses.

“I took a course on Dante, which was really crazy. I’m never going to make it through this. I thought about it for a while and thought the only way I’m going to be able to pass this course is if I draw it. So that’s what I did.”

She put her all into drawing the Circles of Hell. Her professor had never gotten a paper like that. “He was thrilled with it.” She got an A in the course.

“I got my teacher’s license. I proved that I could do it.”

She taught at a private art school in Summerside and lent a hand part-time at Rainbow Valley in nearby Cavendish during the summer season until, in 1990, her husband of thirty years tied an anchor around his neck and threw himself into the North Rustico Harbor waters.

“He was a great guy. I decided to do a three-dimensional sculpture of Al as he was, as a fisherman.”

At first, her plan was to make the commemorative sculpture in cement. “But then I thought, we had just gotten a new fiberglass boat, so I could do it in fiberglass.” It was an idea that would reinvent her from then until now.

The boat was a Provincial, built by Provincial Boat and Marine Limited in Kensington, less than twenty miles west on the north coast. “Earl Davison had a fiberglass plant in Kensington and was producing great fiberglass boats.” They are known for their speed and durability. They are sometimes called “lifetime boats.” Mary went to Kensington to see Earl, who also owned and operated Rainbow Valley.

“I went to see him, and I said, I’ve got something that I’d like to do in fiberglass, so he said, I’ll come down to look at it. He came down to the house this one day and looked at my plan. I got a call a few days later. He offered me a full-time job instead.”

“I need an artist,” Earl said.

“Yeah, I’ll do that,” she said.

The sculpture of Al Smith got made and Mary went to work full-time at Rainbow Valley in Cavendish, a hop, skip, and a jump away from her home.

She never left. She worked seven days a week, May through September, until the water safari adventure amusement park was purchased by Parks Canada in 2005. It has since been remade into Cavendish Grove and become conserved land with a network of walking trails.

Rainbow Valley, named after Lucy Maud Montgomery’s 1919 book “Rainbow Valley,” was thirty six years’ worth of waterslides, animatronics, swan boats, a sea monster, a monorail, roller coaster, castles, suspension bridges, and a flying saucer gift shop. “We tried to add something new every year,” Earl said. “That was a rule.” The other rule-of-thumb was families with smiles plastered all over their faces.

“The most important thing you could do for somebody was to have them all together as a family and help make memories,” said John Davison, Earl’s son who grew up running around the park and as a grown man worked there. “Some of the memories you hear are from people whose parents aren’t with them anymore. But they remember their visits to Rainbow Valley with their parents and those experiences last a lifetime.”

Earl Davison had envisioned the park in 1965, buying and clearing an abandoned apple orchard and filling in a swamp, turning it into ponds. “We borrowed $7,500.00,” he said. “It seemed like an awful lot of money at the time.” When they opened in 1969 admission was fifty cents. Children under five got in free. In 1979 he bought his partners out and eventually expanded the park to sixteen hectares. Most of the attractions were designed and fabricated by him and his crew.

“Rainbow Valley was a unique place to work, because Earl was so creative,” Mary said.

“Mary had a talent,” Earl said. “She could see things, create things, draw, and she seemed to always be able to draw what I told her about.”

He told her about rum running on the island, where there had been a total ban on alcohol from 1901 until 1948. Smugglers laid low off Cavendish in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, avoiding Coast Guard cutters, hiding kegs of hard liquor in the sand dunes and woods at night. When the kegs were empty fishermen often used them to salt mackerel in, the smells of rum and salt fish mixing it up.

She sketched out what became an animated simulated dark ride about booze and bootleggers.

“Mary designed it,” said Earl. “She did all the faces for the characters and helped dress them, too.”

At the end, an animatronic man coming home with a keg of rum in a handcart tells his protesting wife it’s molasses. “Don’t you lie to me,” she says. He takes a step between his wife and his handcart. “I would never lie to you, my smuckins, and if this here’s rum, may lightning strike me right here where I stand.” Every day, morning, noon, and night, a thunderous crack of lightning struck him where he stood.

In the early 1990s Mary approached Earl about mounting a music show. It became Fiddlers and Followers, which became the North Rustico Country Music Festival, which is still going strong. The music festival, staged over the course of a weekend every August at the town’s North Star Arena, concerts as well as workshops and jam sessions, brings together some of Atlantic Canada’s best-known down-home, old-time, country, bluegrass, island-fiddling, folk-inspired music makers.

“We’ve never missed a year. We’re getting older, but I still get really pumped up about it.”

Earl and the Rainbow Valley construction crew built a barn and a stage for Fiddlers and Followers, local talent was secured, and they fabricated a 24-foot fiddle to be a beacon at the front of the building.

“Earl provided the opportunity for it to start. I designed the big fiddle.”

“It was a giant fiddle,” Earl said. In the event, it might have been even more gigantic, given the chance. “We coulda gone higher. It was Mary’s fault. She drew it to be twenty four feet, so that’s what we did.” In 2017 the giant fiddle was moved to the New Brunswick front lawn of fiddle champions Ivan and Vivian Hicks.

“Burns MacDonald and I did shows every day,” Mary said.

When she began playing with Burns MacDonald it was the first time in more than thirty years she played anywhere outside of home or at a house party.

He was the piano player. “I would be in the shop painting, doing artwork, and somebody would say, you’ve got to go for the show.” She would drop everything, grab a guitar, and run to the stage. “I never got tired.” Pete Doiron was their fiddler at the evening shows. “He was one of the best on PEI.” They played together three times a day for twenty-minute stretches.

The first time she heard Burns playing the piano she was working with her boss one floor down.

“I have to go see who that is,” she told Earl.

“I run upstairs, and it was this Burns MacDonald. I went over, stood by him, and we started talking. He never stopped playing while he was talking.”

When she went back downstairs, she said to Earl, “You’ve got to hear this guy. He’s unreal.”

Burns MacDonald got hired on the spot and started playing during intermissions of the Roaring 20s show then on stage. The next year he came from his home in Nova Scotia for the whole season, living in a trailer in the park. “He was there fourteen years steady,” said Mary. “Everybody was just blown away by him.”

Shortly before his death Al Smith had gotten his wife a fiddle.

“We were at a show in Charlottetown and the entertainer was a fiddler. I thought, gee, someday I’m going to learn how to play a fiddle.” Her husband thought it was a good idea and bought her one. But when her husband passed away, Mary put the fiddle back in its case and put it away.

She took it out of its case after a bus tour she had organized to Cape Breton. Burns was the entertainer on the tour. “I said something about fiddles, and he said, you’ll never learn how to play the fiddle.” He might as well have thrown down the gauntlet as made a passing remark.

“That wasn’t the thing to say to me,” Mary said.

Since dusting off the fiddle, and learning how to play it, she’s done well enough to receive the Tera Lynne Touesnard Memorial Award at the 2017 Maritime Fiddle Contest. “It was a humbling experience and one I really don’t deserve,” she said. “It’s a great honor, however, and one I’ll always cherish.” She has also been made a lifetime member of the PEI Fiddle Association.

Mary came to the piano by misadventure.

She had agreed to be a co-host during an on-air fundraiser for Make-A-Wish. After finishing her stint at the station, she went home, but kept track of the auction. She noticed a keyboard valued at more than a thousand dollars wasn’t attracting many bids. She decided to prime the pump.

“I started bidding, figuring when it’s high enough, I’ll stop.” However, she got carried away. “I kept bidding. I thought, I can’t let them outbid me. Just as I put my last bid in, time ran out, and I ended up with the keyboard.” It cost her $800.00.

“I couldn’t afford it, but it was a for a good cause,” she said. “When I got it home, I took my guitar, and since I knew the chords on it, I just figured them out on the piano. I have my own style.” Being self-made means doing things your own way, no matter how much teamwork is involved.

When Mary Smith takes the stage at the North Star Arena, whether as one of the key organizers of the North Rustico Music Festival, or with guitar, fiddle, keyboards in hand, she is within sight of the lighthouse she was born in. There are sixty three lighthouses on Prince Edward Island. More than thirty of them are still active. The North Rustico harbor light is one of the operational ones, sending out five seconds of light every ten seconds.

Lighthouses, like music makers, aren’t narrow-minded about who sees their light. “When you play, never mind who listens to you,” said the pianist Robert Schumann. They shine for all to see. Without a guidepost, steaming into a dark harbor would be a mistake. Without music to brighten the day, getting up in the morning might be a mistake.

Music is in Mary’s bones. She plays with several groups, including Mary Smith and Friends, Touch of Country, and the Country Gentlemen. The North Rustico Choral Group, which performs for seniors, was her brainchild ten years ago.

“I see Mary’s performances at Sunday Night Shenanigans,” said Simona Neufeld, a local music buff and fun fan.

“Music has been a big part of my life,” Mary said. “I’ve met so many great people, some really great friendships.” She plays in living rooms, at outdoor venues, and on motor coach day tours. She often plays at community centers.

“Life would be pretty dull if you just sat at home and watched TV. I guess being born in a lighthouse, I have to be brighter. You have to keep going.”

Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”