By Ed Staskus

I wasn’t a sportswriter or a sports photographer at the time, but I had a media pass so I saw more Cleveland Cavalier games in the flesh during the 1980-81 season than I have ever seen in my life. I saw them from a better seat, too, even though I didn’t have a seat. I sat, stood, or knelt court side, sometimes under the baskets at the base of the stantions or beside the benches, and pretended to be doing something like taking notes. Nobody questioned my Kodak Instamatic Point & Shoot camera or schoolboy spiral notepad, even though the camera was rarely loaded with film and I often forgot to bring a pen.

I got the media pass from my brother, who was a student at Lakeland Community College in Kirtland. He worked part-time for the school newspaper. He was their communications and media man. I had it laminated and wore it clipped on my belt. Whenever anybody bumped me jostling in or out of the arena I checked to make sure the pass was still on my belt. It was worth its weight in gold, getting me in to see the wine and gold whenever I wanted.

The Cavaliers weren’t very good in 1980. Mike Mitchell was their best player. It was a steep drop-off from there. Bill Musselman, who was the coach, didn’t have much to work with and it showed on his game face game after game. The team finished the year twenty four games out of first place.

My drive to the Richfield Coliseum in Richfield Township, twenty-five miles south of where I lived near downtown Cleveland, was long and longer, especially whenever they were playing a league-leading team like the Boston Celtics or Philadelphia 76ers. I soon enough learned to go early or get stuck in traffic. The Richfield Coliseum was Larry Bird’s favorite basketball arena, but he didn’t have to drive there. An interstate and a turnpike dumped cars onto a two-lane road in the middle of nowhere. It was a snail’s pace at the best of times. The traffic issues got worse the worse the weather got. In addition, the single level concourse made for massive congestion among the fans and nobody liked that, either. I had to pay for parking, which I didn’t like, although I brushed it off. Once I flashed my pass and strolled in without a hitch I was happy again.

A lot went on at the Richfield, Coliseum, including concerts, truck pulls, rodeos, circuses, ice shows, wrestling, hockey, and indoor soccer. The arena hosted a championship boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Chuck Wepner in the mid-70s. The fight went to the bitter end, the human punching bag holding on for dear life but going down nineteen seconds before the final bell, losing in a TKO and inspiring Sylvester Stallone’s movie “Rocky.”

The Cavaliers weren’t the first pro basketball team in Cleveland. The first three teams, starting in 1924, were the Rosenblums, the Rebels, and the Pipers. When the “Miracle of Richfield” happened during the 1975 season, the Cavaliers advancing to the Eastern Conference Finals, everybody forgot about the team’s basketball pioneers, if they had ever thought about them in the first place.

The Richfield Coliseum opened in October 1974 with Frank Sinatra doing the honors. When he sang “My Way” the sold-out crowd roared its approval. “My friend, I’ll make it clear, I’ll state my case, of which I am certain.” Nobody roared louder than Nick Mileti. He had been a prosecutor in the inner-ring suburb of Lakewood, but then got the bug. “I want to have fun, make some dough, and leave a few footprints,” he told sportswriter Bob Oates of the Los Angeles Times.

“Nick could sell you the Brooklyn Bridge, whether you wanted it or not,” said Bill Fitch, the Cavaliers coach from 1970 to 1979. The new arena in the middle of nowhere was the immigrant Sicilian son’s Brooklyn Bridge to glory. “My daddy was a machinist who came over as a teenager and had a dream that I was to wear a white shirt,” he said.

He started by buying the Cleveland Arena and the city’s hockey team. He owned the Cleveland Indians baseball team for a while and then picked up the basketball team. He wasn’t using his own money, but he doctored it to look like it was his. After a while he took a good look at the 30-plus-year-old Cleveland Arena with its bad plumbing and a seating capacity of only 11,000. What he saw was money flying out the window. The players called it “The Black Hole of Calcutta.” They later called the new arena “The Palace on the Prairie.”

“We met with the guy running the old arena,” Nick Mileti said. “On the wall, there was a calendar, and I said, ‘Why is it all white?’ They said, ‘Because we don’t have any events.’ It was an incredible situation. I bought the Barons and the arena, and after that, the first call I made was to Walter Kennedy, the commissioner of the NBA, and said I wanted a franchise. And two years later, I got one.”

When in the early 1970s he decided on moving the basketball team halfway to Akron to do better business, every Cleveland politician and businessman was against the idea. They wanted to revitalize downtown, not vitalize someplace in the boondocks. They wanted the cash flow of twenty thousand fans driving in forty or fifty times a season. They wanted the countless concerts, circuses, and events the venue would host. They wanted the tax revenue. They didn’t get what they wanted. But that was what Nick Mileti wanted, and that was that.

I didn’t get to know any broadcasters doing the games, but I got to know some of the writers and cameramen well enough to say hello. They were guys like Bill Nichols, Chuck Heaton, and Burt Graeff. One or the other of them was always giving me the fisheye. When I saw it happening, I pretended to be taking a picture with my Instamatic. The only newshound I was on more than hello and goodbye terms was Pete Gaughan. He was a sportswriter for the SunMedia suburban papers, writing about golf, high school, college, and pro sports, and anything else that involved hitting, kicking, throwing, or catching a ball. I met him while refereeing flag football Sunday mornings at Lakeland Community College.

My brother had started a flag football league there with four teams. By 1980 he had two fields and fourteen teams. The teams were mainly made up of former high school players. He and I were the only two refs at first, but as more teams joined, he needed a second and third two-man crew. He paid $20.00 to each ref each game, but still had trouble recruiting and keeping crews for the Sunday morning games. When Pete Gaughan volunteered and my brother took him on, it was scraping the bottom of the barrel. Pete may have known all about local sports, but he didn’t know how to be on time and was indifferent about the rules.

The first Sunday I met him he misjudged a parking space and brought his rust bucket to a stop on the wrong side of the curb. When the driver’s door swung open, the car still running, a half dozen empty Budweiser cans rolled out, a leg flopped here and there, and he finally staggered out of the car in a cloud of cigarette smoke. He looked like hell, like he hadn’t slept in a week. I turned his car off while my brother got him into ref’s clothes, gave him a whistle and a penalty flag, and decided he would work with me.

“Thanks, bro,” I said while he trotted off to another field.

Pete worked behind the offensive line while I worked downfield. He didn’t blow his whistle or throw his yellow rag once, not even when there was blood. One of the teams was made up of former Mentor High School players, and unlike most of the teams, they ran the ball more than they threw it. They were the number one team in the flag football league because they had played together in school and knew how to execute. One guy on the opposing team got tired of being battered by the relentless running attack, and when the halfback came through the line one more time the ball tucked under his arm, the other arm swatting hands away, he didn’t bother trying to reach for either of the flags on the runner’s waist. He raised his forearm head high and let the halfback’s nose run into it. He went down like a shot and blood gushed out of his nose. Pete spotted the ball at the spot and stepped to the side, lighting up a cigarette.

We called 911 and after an EMS truck showed up, they drove off with him, telling us his cheekbone was fractured along with his messed-up nose. We called the game. The Mentor boys were up by eight touchdowns anyway. Pete popped a Budweiser.

By the 1980 season the “Miracle of Richfield” was five years in the dustbin and Nick Mileti had given up his title as president of the Cavaliers, sold his interest, and control of the team went to Ted Stepien, the King of Errors. There weren’t going to be any miracles under his reign. The NBA stayed busy writing rules addressing some of the crazy things he was prone to doing. He traded away five consecutive first-round picks. The wrote the Stepien Rule, which states no team can trade away consecutive first-round draft picks.

In the meantime, I tried to see all the games involving the better teams in the league. The Cavaliers were a half-good team who could keep up with other half-bad teams. They had trouble with the cream of the crop. That year they went 1 and 4 against the Celtics, 1 and 5 against the Bulls, 0 and 5 against the Knicks, 0 and 6 against the Bucks, and 0 and 6 against the 76ers.

The Philadelphia team was my favorite team. They were always in the hunt for the title. Maurice Cheeks and Doug Collins were the guards. Bobby “The Secretary of Defense” Jones cleaned up around the basket. Julius “Dr. J” Erving and Daryl “Dr. Dunkenstein” Dawkins led the scoring parade. When the doctors were in the house, they were good for almost fifty points. Julius Erving was menacing enough, but Daryl Dawkins was a menace unto himself.

A year earlier in a game against the Kansas City Kings in KC, dunking the ball with enthusiasm, Daryl broke the backboard, sending both teams ducking. Three weeks later, he did it again at home against the San Antonio Spurs. The next week the NBA wrote a new rule that smashing a backboard to smithereens was wrong, so wrong that it would result in a fine and suspension.

Daryl named his backboard-breaking dunks “The Chocolate-Thunder-Flying, Teeth-Shaking, Glass-Breaking, Rump-Roasting, Wham-Bam, Glass-Breaker-I-Am-Jams.” His other dunks earned their own names, like the Rim Wrecker, the In-Your-Face Disgrace, the Spine-Chiller Supreme, and the Greyhound Special, for when he went coast to coast. “When I dunk, I want to go straight up, and put it down on somebody.”

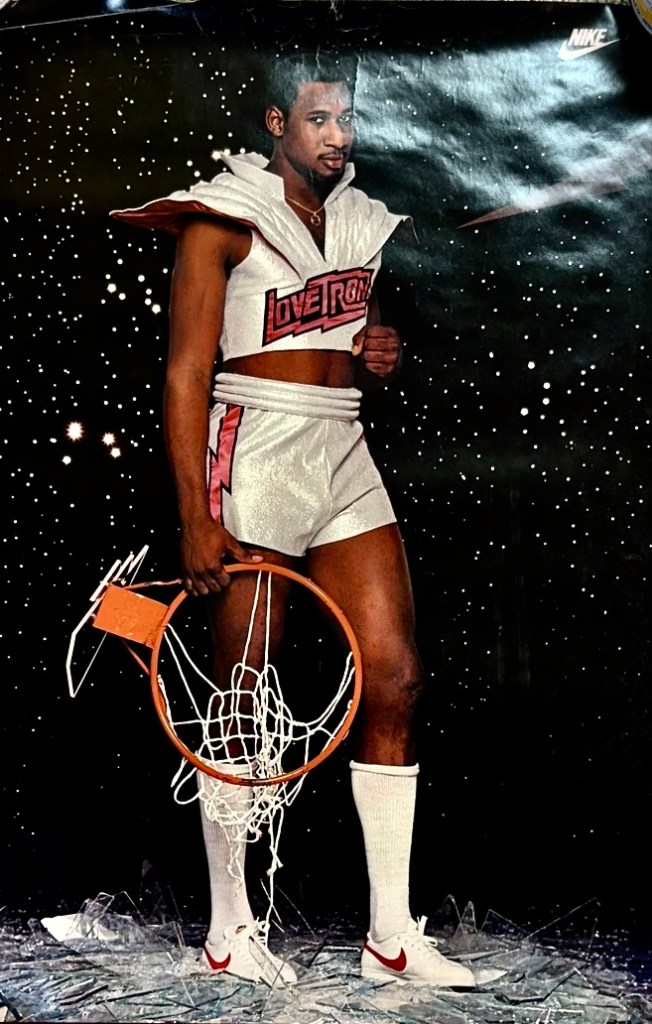

His nicknames were Sir Slam, Chocolate Thunder, and Dr. Dunkenstein. He wore a LoveTron t-shirt while warming up. He told the Cleveland sportswriters he was an alien from the planet LoveTron, where he spent the off-season practicing “interplanetary funkmanship” with his girlfriend Juicy Lucy. The reporters scribbled it down like it was sirloin.

His coach asked him to tone it down. “All the talk and bravado, enough,” Billy Cunningham said. The next day at practice Daryl told his teammates, “I’m not talking today. Coach made me Thunder Down Under.” It didn’t last long. He went back to talking the next day.

Daryl Dawkins was in his mid-20s, six foot eleven, and 260 pounds of beef, brawn, and swagger. The Cavalier centers were Kim Hughes and Bill Lambeer, both six eleven, but both slower and skinnier than Daryl, who wore gold chains during games. One of them featured a cross while another one proclaimed Sir Slam in gold script. Sometimes, he would shave his head and oil it, along with wearing a gold pirate’s earring.

The year before he had averaged almost 15 points and 9 rebounds, helping the 76ers to the NBA Finals, which they lost in six games to the Los Angeles Lakers. I watched him go coast to coast against a back-pedaling Bill Lambeer one night. If it had been the other Cavalier center, Kim Hughes, about 40 pounds lighter than Daryl, he wouldn’t have even bothered back-pedaling. Bill Lambeer was far more stubborn. All the way to the inevitable slam dunk Daryl’s gold chains swung one way and the other way slapping at Bill’s face until he finally ducked and covered. The next year the NBA forbade the wearing of any jewelry while playing ball.

The last three games I saw at the Richfield Coliseum were the last three games of the season. The Cavaliers lost by 26 to the Bucks, by 21 to the 76ers, and by 35 to the Bullets. It had been a long year. The opening game of the next season boded another long year when the wine and gold lost to the 76ers by 24. But before that game was even played, I didn’t have a media pass anymore and wasn’t planning on going back to the Richfield Coliseum anytime soon. I didn’t have a dependable car and God forbid I break down in the cow pastures of Summit County in the middle of the night.

I missed going out there, missed the lights and noise, groaning and cheering, being on the floor, the action and excitement, the coaches fuming and cursing, and the players putting up with venomous fans sitting behind them. Daryl Dawkins wasn’t big on putting up with anything. When he flaked on a dunk one night, hearing the catcalls, he kicked somebody’s extra-large Coke off the floor, sticky sugar water spraying on everybody in the big-ticket seats. He didn’t look back and didn’t apologize. I kept a firm grip on my jumbo soft pretzel.

After the Cleveland Cavaliers returned to Cleveland to a new arena the Palace on the Prairie closed and the parking lot went to weeds and shadows. I walked to games downtown a couple of times, but the atmosphere was more corporate than cutthroat and I didn’t go back. Besides, they were charging corporate prices for the tickets, and I wasn’t about to bust my piggybank to cheer grown men in shorts bouncing a ball from one end of a hardwood floor to the other end. Besides, the last time I checked on Daryl Dawkins, he was playing for the Harlem Globetrotters. That was where the fun and games were.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street at http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

The end of summer, New York City, 1956. Stickball in the streets and the Mob on the make. President Eisenhower on his way to Ebbets Field for the opening game of the World Series. A torpedo waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication