By Ed Staskus

Some men are good at farming. Other men are good at fishing. Merchants and tradesmen keep them in gear and goods. Most men are good for something, although some are good for nothing. Kieran Foyle wasn’t a man good at doing nothing. He didn’t know fishing or farming but was familiar with horses. He was going to make a horse farm and make his way on Prince Edward Island that way.

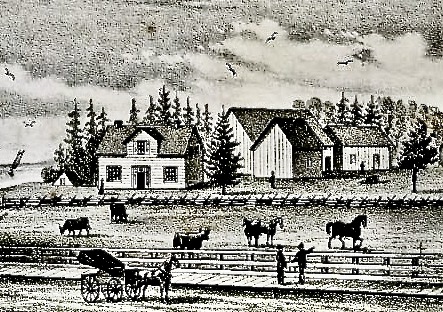

He stayed on the cove where he landed, building a house. He cut, limbed, and sawed trees by hand and split blocks with an axe. The wood would be ready for a stove and fireplace next year. In the meantime, he bought a load of coal from a passing schooner. He found dampness nearby and looked for an underground spring. When he found it, he dug it out for drinking water, saving himself the work and expense of digging a well. Whenever he could he cleared land. It was one stump at a time, pulling them out with a team of draft horses. Sometimes it seemed like it was all he did.

“The islander making a new farm cuts down the trees as fast as possible until a few square yards of the blue sky can be seen above. Roots and branches lying on the ground are set on fire and sometimes the forest catches fire acres of timber are burned,” is how Walter Johnson, who came to the island to start Sunday schools, described it.

Kieran put enough salted cod away to feed a God-fearing family of Acadians. When the weather changed for the worse, he ate, smoked, read, and slept through the season, living in his union suit. The dead of winter arrived near the beginning of January and kept at it through February. The daytime high temperatures were below zero and the overnight low temperatures were less than below zero. After spring arrived and the Prince Consort proved true to his word, his land grant delivered, stamped with officialdom, he continued clearing land and building his house.

He wasn’t a food growing man, but he had to eat. His first task was putting in a root garden of beets, turnips, and potatoes. They would store well during the winter. He made sure there were onions. They added flavor to food and were a remedy to fight off colds. Whenever he started coughing or sneezing, he stripped and rubbed himself all over with goose grease, stuffing a handful of sliced onions into his underwear. He always felt better afterwards.

Corn, peas, and beans could be dried and stored for soup. A bachelor might even live on the fare. Rhubarb was a perennial and a harbinger of warmer days. After a long winter it was the first fresh produce. He planted plenty of it. The island had a short but robust growing season. He woke up before sunrise and worked until dusk. He kept at it every day. The Sabbath meant nothing to him.

The Prince of Wales visited Prince Edward Island that summer during his tour of British North America, arriving in a squadron consisting of the Nile, the Flying Fish, and three more men-of-war. The Nile accidentally grounded trying to enter Charlottetown’s harbor. Once the tide came in the unlucky boat sailed away towards Quebec. Spectators cheered Bertie’s progress to Government House on streets decorated with spruce arches.

“The town is a long straggling place, built almost entirely of wood, and presents few objects of interest,” the Prince of Wales wrote home to his mother Queen Victoria. She was too busy to reply with commiseration. England had been importing loads of Southern cotton for its textile industries, which were exporting loads of cloth back to the United States. Queen Victoria was on the side of Johnny Reb, but Prince Albert cautioned her to not take sides and meddle in foreign affairs. When the Union Navy seized a British ship with two Johnny Reb’s on board, there was an outcry in Parliament. A declaration of war was submitted for the queen’s signature. In the meantime her consort hid her quill pen.

Prince Albert died within the year, but not his admonishments about politics. Queen Victoria stuck to his guns for the next forty years. “I love peace and quiet,” she said. “I hate politics and turmoil. We women are not made for governing, and if we are good women, we must dislike these masculine occupations.” A third war with the United States would have been problematic.

It was a cloudy afternoon, but when it cleared, the Prince of Wales went horseback riding. That evening there was a dress dinner and ball at the Province Buildings. His lordship took a minute to step out onto a balcony. “Some Indians grouped themselves on the lawn, dressed in their gay attire, the headgear of the women recalling the tall caps of Normandy,” he told an aide. When the squadron ferrying the royal party embarked towards the mainland it was in a heavy rain. No one who didn’t need to be on deck wasn’t on deck. There were no spectators in the harbor waving hats and kerchiefs. Even the Mi’kmaq stayed away.

“Our visit it is to be hoped has done much good in drawing forth decided evidence of the loyalty of the colonists to the Queen,” the Prince of Wales proclaimed. Colonial loyalty and Queen Victoria’s confidence in her colonists were soon to be tested. It was not yet viable, but Confederation was rearing its head. He played cards and lost money on his way to Quebec. He was loath to ante up. The wealthy are always more tight-fisted than the beggarly.

Kieran hadn’t bothered making the long trip into town, having already gotten what he wanted from the royal family. The Prince of Wales was a playboy. Kieran knew he didn’t care whether any of his subjects lived or died. When the Irishman was able to at last move into his house, he started work on a horse barn. It would be large, more than large enough for stabling animals, milking cattle, and storing tools. The haymow would hold more than forty tons to feed his animals during the winter.

At the same time, he started looking for a wife. He needed help inside the house so he could work outside the house. He needed somebody he could trust and talk to. Life without a woman on Prince Edward Island was a hard life. He found his wife-to-be at the same time he was finally finishing the barn.

He met her in the cash provision store in Cavendish. Siobhan Regan was 19 years old, a few years older than half his age. She wasn’t pretty or well off but looked sturdy and round bottomed. He was sure she could bear children without killing herself or the infant. She could read, although she seldom did, except for the Good Book. She was ruddy cheeked with big teeth. She was a quiet woman, which suited him, who used the spoken word only for what it was worth.

They were married and snug in their new house, home from the wedding in a buggy retrofitted with sleigh runners, the night before the last big snowfall in April. She got pregnant on Easter Sunday and stayed more-or-less pregnant for the next ten years, bearing six children, all of whom survived. Her husband refused the services of the village’s midwives, refused the services of the doctor, and delivered the children himself. He threw quacksalvers out the door with a curse and a kick. He trusted them as much as he trusted the Prince of Wales. They peddled tonics saturated with moonshine and opium. He had had some of both, enough to know they were no good for the sick or healthy, more likely to kill than not. He never drank port, punch, or whiskey, rather drinking his own homemade beer. He liked to wrap up the day with a pint and his pipe.

He knew cholera and typhus had something to do with uncleanliness, although he didn’t know what. He had seen enough of it on ships, where straw mattresses were rarely destroyed after somebody died from dysentery while laying on them. He ran a tight ship, keeping his house and grounds in working order. He didn’t let his livestock near the spring, instead taking them downstream. He had seen the toll in towns where garbage was thrown into the street and left there to rot. He and his wife were inoculated against smallpox, and as the children got on their feet, so were they. He brooked no objections about it.

Kieran wasn’t going to throw the dice with the lives of his children. Five of his ten brothers and sisters had died before they reached adulthood in the Land of Saints and Scholars. Their overlords had something to do with it, famine had something to do with it, and their rude lives the rest of it, putting them into early graves. One of them died on the kitchen table where a barber was bleeding him. He bled to death. They buried him in cold sod. The family shunned the barber for always afterwards.

Siobhan took a breather from childbearing towards the end of the decade. Her husband and she went to Charlottetown twice that summer to see shows at St. Andrew’s Hall. They saw “Box and Cox” and “Fortune’s Frolic.” Both of them were directed by the eccentric Wentworth Stevenson, an actress and music teacher trained in London who had formed the Charlottetown Amateur Dramatic Club.

They stayed at Mrs. Rankin’s Hotel, having breakfast and dinner there, walking about the city, stopping for tea when the occasion arose, and spent their otherwise not engaged hours making a new baby. When they were done, they went home. The children weren’t surprised months later when told another one of them was on the way.

Every farm on Prince Edward had a stable of horses for work and transport. Most farmers used draft horses for hard labor, the nearly one-ton animals two-in-hand plowing fields, bringing in hay, and hauling manure. It was his good fortune to know horses inside and out, whether big or small. The carrying capacity of his land was more than a hundred horses. He wasn’t planning on that many, although a hundred would suit him well enough if it came to that. He was going to grow most of his own food and sell horses for the rest of life’s essentials and pleasures.

By 1867 when Prince Edward Island rejected the thought of joining the Confederation, even though it hosted the Charlottetown Conference in 1864 where it was first proposed, he was well on his way to making his horse farm a going concern. Confederation didn’t concern him, one way of the other. Many islanders wanted to stay part of Great Britain. Others wanted to be annexed by the United States. Some thought becoming a dominion on their own was best. He kept his eyes on the prize, which were his family and his farm.

John Macdonald, the country’s first Prime Minister, who was always worried about American expansionism, tried to coax the island into the union with incentives, but it wasn’t until they were faced with a crisis that Prince Edward Island’s leaders reconsidered his various offers. It was when they put themselves into a hole that John Macdonald’s efforts paid off.

A coastline-to-coastline railway-building plan gone bad put Prince Edward Island into debt. It spawned a banking crisis. Ottawa agreed to take over the debt and prop up the financing needed to resume railway construction. Parliament Hill had only been in business for ten years, but it learned its business fast. There was a demand for year-round steamer service between the island and the mainland. Ottawa agreed to the demand. The province wanted money to buy back land owned by absentee landlords. Ottawa agreed to that, too. In the event, the politics and wrangling went on. “Let us pray,” Kieran said, even though he wasn’t a church-going man. “Oh, Lord, give us strength to bear that which is about to be inflicted upon us. Be merciful with them, oh, Lord, for they know not what they are doing.” He neglected to say amen.

He was better off than many people on the island. He had some amount of hard cash while most islanders had no cash to speak of and bartered almost everything. When the chance arose to make a killing during the horse disease of 1872, he took it. The pandemic started in a pasture near Toronto. Inside a year it spread across Canada. Mules, donkeys, and horses got too sick to work. They suffered from exhaustion. They coughed, ran a fever, and keeled over getting out of their barns and stables. Delivering lumber from sawmills or beer barrels to saloons killed them outright. They died like flies.

“There are not a hundred horses in the city free from the disease,” a newspaper editor in Ottawa wrote. “We have very few horses unaffected,” another editor in Montreal wrote.“ The only place the pandemic didn’t touch was Prince Edward Island. “When the disease was raging in the other provinces, our navigation was closed, and our island entirely cut off, in the way of export or import from the mainland, which in fact must have been the reason it did not cross to our shores,” wrote the editor of the island’s Patriot newspaper.

Kieran drove forty horses to Summerside where they were loaded on two ships for crossing the Northumberland Straight. Once on shore they were walked to the railhead in New Brunswick and shipped by railcar to Montreal, where money for horses was better than anywhere else. After he was paid he secreted the money inside his shirt. He kept his jacket buttoned up to the collar all the way home.

The next year the island’s voters were given the option of accepting Confederation or going it alone and seeing their local taxes go sky high. “I hope they can finally make up their minds,” Kieran said. Most voters chose Confederation, voting their pocketbooks. Prince Edward Island officially joined Canada on July 1, 1873. The weather that day was foul and then a storm rolled in. Lightning lit up the low dark clouds, followed a second later by sonic booms. Foxes lay low in their foxholes. The night wasn’t fit for man or beast.

It was two years later in August, lightning bolts slashing the sky, that the prize horse on Foyle land spooked and kicked Kieran in the head, knocking an eye out, breaking his jaw, and fracturing his skull. Everything he knew about horses, as well as the money from the sale of them in Montreal, which he had hidden in a hole behind the barn, flew out the window with his soul. The gates of both Heaven and Hell opened wide to admit him. He tossed the Devil’s invitation aside.

Flags flew on the island that same August when George Coles died in Charlottetown. He had been the first premier of Prince Edward Island and one of the Fathers of Confederation. It hadn’t kept him from fighting a duel with Edward Palmer, another Father of Confederation. He had been a feisty man. He was convicted of assault over the duel. He spent a month in jail while still serving in the provincial government. His twelve children visited him every day and brought him beer every day. He had been a brewer earlier in life. He always said, “There is no beer in Heaven which is why we drink it here.”

Siobhan folded her flag and buried it with her husband in the St. Peter’s boneyard up the hill. After the interment, her children gathered around her, she looked out on the Atlantic Ocean from the top of the rise. Her husband had crossed the western ocean at peril to himself to make his fortune, no matter what it might be. He was gone now but the land was still theirs. She would never give it up. It would always be theirs. Her children’s children would bear fruit there.

Siobhan wasn’t going anywhere, no matter whether it was Canada or the United States or anywhere else on the island. She couldn’t raise the dead, but she could raise her children on the farm her husband had made. She was determined none of them would ever forget their father. Foyle’s Cove would stay what it was and where it was.

She started the slow walk home with her sick at heart brood. They walked down the red road to the cove and their farm. The smallest of her issue, a girl with pigtails flapping, pulled at her mother’s dress.

“Mammy, I have a secret to tell you.”

Excerpted from the book “Ebb Tide.”

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Ebb Tide” by Ed Staskus

“A thriller in the Maritimes, out of the past, a double cross, and a fight to the finish.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Available at Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CV9MRG55

Summer, 1989. A small town on Prince Edward Island. Mob money on the move gone missing. Two hired guns from Montreal. A constable working the back roads stands in the way.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication

A great story. I could visualize their lives like I was there

LikeLike