By Ed Staskus

The Yellow House on the south side of North Rustico on Prince Edward Island isn’t any different than most houses. It has a front door and back door, two stories, two gables, two chimneys, plenty of windows, and a latter-day addition The only difference is that it’s on a fishing harbor on the ocean, has its own parking lot, and isn’t strictly a family house anymore.

It’s a family restaurant, takeout, and catering house.

On sunny days the Yellow House looks like it is painted in sunlight. On its open to close days, if it’s overcast on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, light streams out of the windows brightening the gloom. On catering days it buzzes with energy and deadlines.

When Marie “Patsy” Gallant died in 2009, the home she had lived in on Harbourview Drive, next to Barry Doucette’s Deep Sea Fishing, went empty and dark.

“She let the town buy the house, but they didn’t have any money to renovate or turn it anything,” said Mike Levy. “They wanted a restaurant, something that would service the community.” Six years later he and his wife, Jennifer, recently become residents on the north-central shore of PEI, decided to give it their best shot.

“We had to fix it up so we started looking for funding. We couldn’t find any. Nobody wants to risk a restaurant, even though we had worked in finance and banking and worked in the food and beverage industry, been servers bartenders cooks managers.”

Between them they had two university degrees, two degrees from the Culinary Institute of Canada at Holland College, and had already gotten a business, the Green Island Catering Company, off the ground. They had been catering the Prince Edward Island Legislature’s “Speaker’s Tartan Tea” for three years.

“It’s easier to get a loan for a food truck, since the truck is an asset,” said Mike.

Lenders are understandably skittish, given that 60% of eatery start-ups go out of business within a year and 80% within five years. Even though many entrepreneurs believe failure isn’t an option so long as their determination to succeed is strong enough, it is more often the case, as Winston Churchill said, “Success consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.”

No matter what your best shot is, doing almost anything worthwhile carries with it some kind of risk. It’s only when you don’t try, on the other hand, when you don’t play ball with failure as a possibility, you don’t take any risks. But, since Mike Levy getting to the Yellow House was, in the first place, only made possible by playing poker, he stepped up to the plate.

“Some friends and I were playing poker on-line,” he said. “I had written a paper in university about gambling sites. I loved poker because there is a way to play that isn’t just pure luck.”

A native of Unionville, a once-farmland suburb of Toronto, Mike was living and working in Calgary, Alberta, after graduating from nearby Lethbridge College. “The money we won that night didn’t split evenly, so I let my buddies have it so long as they let me have the ticket to get into the next tournament.”

He couldn’t lose.

“I knew enough to know it wasn’t skill. No matter what I did it didn’t matter. I made it up to twenty grand. Anybody tells you gambling isn’t an addiction is full of it. I could feel myself itching to go back to the computer and play more. The only thing that saved me was the thought, in the back of my mind, Jen will kill me.”

Jennifer Johnston, his wife-to-be, was finishing her degree at Leftbridge College. Mike was working at the Dockside Bar & Grill. A meat packing plant squatted next door to the restaurant. Working behind the bar, some of his tips were in lieu of cash.

“I’d come home with a box of steaks.”

After dinner – after watching “After the Sunset” – a movie about a master thief who retires to the archipelago following his last big score, Mike popped the question one night. “There was a song in the movie, the pineapple song, and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I finally said, Jen, do you want to try the Caribbean?”

“What? Where?” Jennifer asked.

“I figured she was going to ask.” He had done his research beforehand. “The Grand Cayman Islands fit all of our requirements. The history was British, the laws were similar to what we were used to, and the currency was stable. It was safe and everyone spoke English.”

They parlayed their winnings into moving lock stock and barrel three thousand miles southeast of the Canadian Rockies, from where high temperatures in summer in Cowtown meant the mid-70s, to where low temperatures never fall below the mid-70s, summer or winter.

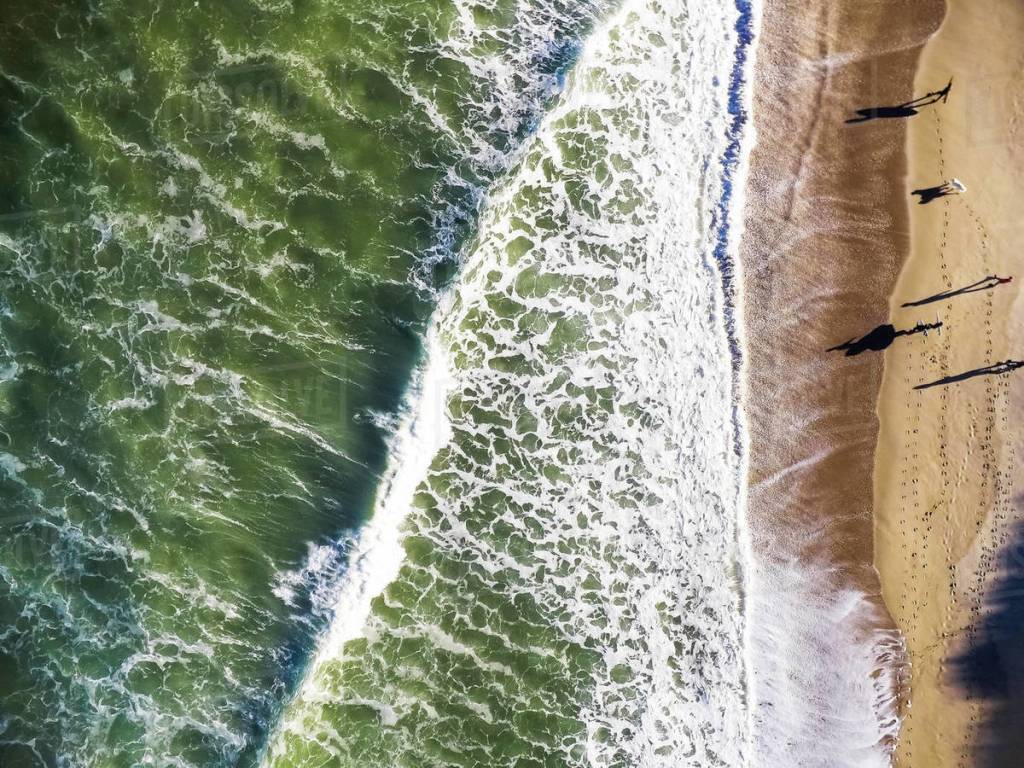

Grand Cayman is the largest of the three islands. Hundreds of offshore banks and tourism drive the economy. Orchids, mahogany and palm trees, and many kinds of fruit trees dot the landscape, as do turtles and racer snakes. They are known as racer snakes because they tend to race away when encountered.

After living in town they found lodgings on the seashore. “A doctor who owned a beach house needed somebody to look after the property,” he said. They lived in the caretaker’s apartment. “It was only rented twice a year, by a nun who was a writer, very active politically. She drank me under the table twice a year.”

Jennifer found work immediately as a server at the Royal Palms on Seven Mile Beach. “She’s a cute blonde girl, she got hired in ten seconds.” The Royal Palms is the closest beach bar to the cruise ship port. She later worked as one of the managers at the Dolphin Swim Club, where tourists paid to swim with fish. “I’d visit her and a dolphin would go flying by her office window.”

It took Mike a few weeks, but he finally found a job as a junior bartender at the Westin. “You get all the bad shifts at first,” he said. “You get screwed. You make no money. I put in my dues. After a few months I got better shifts.”

Mike and Jennifer worked in Grand Cayman for almost three years. “It’s a very stratified economy,” said Mike. “You’re either very rich or very poor. But it was semi-affordable for us.” On off days they rode their Vespa around the island, taking martial arts and yoga classes on the beach. “Afterwards we’d swim in the ocean, go out for brunch.”

He learned to get along with his boss. “He had been down there for more than thirty years, from Saskatchewan. He was a bald-headed, serious-looking, aggressive-looking guy. Everybody called him Bitter Bob. When I found out why, I felt bad.”

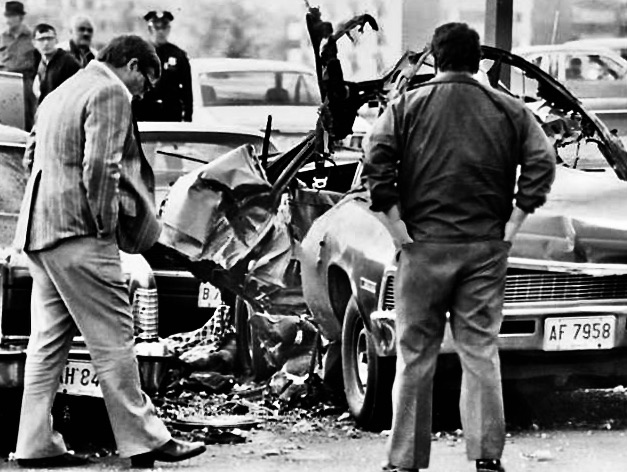

Thirty-or-so years earlier, with his island sweetheart, visiting Miami where he planned to propose, she was killed in an accident in the street, run down by a city bus. He went back to Grand Cayman and never talked about what happened.

Many years later, shortly before Mike and Jennifer’s leave-taking of Grand Cayman, Bitter Bob and his friend Fabio Carletti came out on top.

“Fabio grew up in rural Italy, flamboyantly gay, and his village chased him out,” said Mike. “He and Bob bought a nothing-special plot of land on the west end of the island, except it turned out their little acre had the only deep-water well in the area. They sold it for millions.”

Fabio went back to Italy and bought his mother a car. He bought her a big house. He told off all the villagers, as well.

“Bob sorted himself out, was getting happy, but when I told him we were leaving he held a grudge for months. You get attached to people down there.”

The couple returned to Toronto to get married in order that both of their Ontario families could celebrate the nuptials. It was just in time for Mike’s grandfather to make it to the wedding, too. “He passed away a few months later on the only golf course he ever got a hole-in-one in his entire life.”

He suffered a heart attack walking up the hill to the green of that same hole.

Mike’s family has long been entrepreneurs and business people. They broke ground for Mastermind Toys, a 300-square-foot store, in 1984 in Toronto. It became a chain of toy stores that became Canada’s largest specialty toy and children’s books retailer. “I picked up our first shipment of Beanie Babies,” said Mike Levy, who was then a teenager. “I remember thinking, this is the stupidest thing ever.” By the mid-1990s Beanie Babies had become a craze. In 2010 Andy and Jon Levy collaborated with Birch Hill Equity Partners, masterminding the company’s national expansion.

After high school Mike joined the army. He was 18-years-old when he was sent on his first out-of-country mission. “They sent us to Fort Benning to train with the Rangers.” The US Army Rangers describe themselves as an agile, flexible, and lethal force. One of their beliefs is “complete the mission, though I be the lone survivor.“

The only thing they’re afraid of, it turns out, are snow snakes.

Fort Benning is named after a Civil War-era Confederate States general and is ‘Home of the Infantry’ in the United States. The Canadians marched in the woods all day carrying nearly a hundred pounds of gear and rucksack. They went on simulated search-and-destroy exercises at night. They set up bivouacs in the dark, exhausted, in the middle of nowhere.

When they befriended a troop of American counterparts being posted to the far north, they warned them about Canada’s deadly snow snakes. “Heading up north, eh? The snow snakes are bad this year.” They were met with blank stares.

“What’s a snow snake?”

“They tunnel through the snow. They’ve got long fangs and can bite right through your boots.”

“My God! Are they poisonous?”

“You know the two-step? With those things, they bite you, it’s more like one step.”

The entrepreneurial Canadians offered the Americans their own down-home antidote. It looked like a can of tuna fish with a label that said “Arctic Snow Snake Bite Kit”. The reason it looked like a can of tuna fish was because it was a can of tuna fish with an improvised label the Canadians had designed and printed and stuck on the can.

They sold the antidote like hot cakes for ten dollars a can until they were caught. “Some moron had done it the year before, so they caught us in about twenty minutes.”

“Don’t be idiots,” their commanding officer said.

“They let us go even though they were mad.”

When Mike Levy boarded the plane back to Canada the following month he was told to never come back to Fort Benning. “I’m not sure if the ban is still in place,” he said. In any event, he was leaving the army. “I went off to university the next year.”

After getting married Mike and Jennifer flew to Prince Edward Island for their honeymoon. They stayed at the Inn at St. Peters. “We loved it.” They went to the Provincial Plowing Match and Agricultural Fair in nearby Dundas. Jennifer entered the Wife Hollering Contest.

“You literally had to call your husband to dinner,” said Mike. “I was wandering around a field when I heard my name shrieked out. I stood at attention. The guys around me, I could see them thinking, the poor bastard, I wonder what he did.”

Jennifer Levy won first prize.

“Many of the Canadians we knew in Grand Cayman were from Prince Edward Island,” said Mike. “They always said PEI had good people, good food, and was a great place. That is where you want to go.”

In 2011 the Levy’s moved to PEI and enrolled in the two-year program at the Culinary Institute. In the meantime they cut their teeth working in the kitchen at the Inn at St. Peters, the Orange Lunch Box, the province’s first food truck, and the Delta Hotel in downtown Charlottetown. On his first shift his first day at the Delta, the chef, Javier Alarco, asked him if he had ever shucked a lobster.

“A couple, at school,” said Mike.

“Oh, good. There is a dinner party for the Liberal party tonight. We’ve got 600 lobsters. The kitchen’s got three hours to shuck them.”

Shucking a lobster means twisting off the large claws, separating the tail from the body, breaking off the tail flippers, opening the body, and extracting all the meat. “My first thought was, that’s not going to happen. But, we got it done.” The next day a hundred pounds of potatoes, a hundred pounds of carrots, a hundred pounds of celery, and a hundred pounds of turnips were delivered to his work surface.

“Small dice, three hours, go,” said Chef Alarco.

“That hurt!” said Mike.

The politicians wining and dining in the ballroom at the Delta might have wondered, how hard can it be to boil a lobster? The work in a commercial professional kitchen is hard, hard keeping track of all the sharp knives and sharp edges of stainless steel, hard on your arms and shoulders and back from lifting all during your shift, hard on your legs from being on them all the time. There is nothing that requires a chair for the doing. There isn’t any time to sit, anyway.

There isn’t any time for explaining and complaining.

After finishing culinary school the Levy’s had a plan. Their plan was to work on privately owned yachts plying the high seas. “We were going to find a billionaire who wanted a private chef,” said Mike. “We had the connections from working in Grand Cayman. The pay is outrageous.”

Most super-yachts spend winters in the Caribbean and summers in the Mediterranean. Sometimes they are chartered and other times they are anchored in quiet spots with their owner. Produce has to be bought in port towns, but fishermen often deliver fresh catch to the boat. Although chefs are disconnected from their family and friends for weeks and months, they accrue their wages since there is nowhere to spend it.

“When you’re done they give you a check and away you go,” said Mike. “I thought that was brilliant. That’s what we were preparing to do.” But, sometimes your way of life happens to you, not the other way around, or as John Lennon said, “Life is what happens while you’re busy making other plans.”

Before Mike and Jennifer could sail away they got a phone call from Ontario’s Child Protective Services. Jennifer’s sister, beset by problems with drugs and drink, and the mother of two children, emotionally neglected and in-and-out of care, was on the threshold of losing her children.

“We are going to adopt the children out, unless you, as eligible family members, take them, and agree to make PEI their home,” they were told.

“You have to declare your intent within 24 hours, yes or no.”

The children, Jacob and Madeline, were 7 and 12-years-old. “They had been moving from shelter to shelter, living in crappy apartments. They weren’t living, just surviving, no opportunities. It’s not that I love kids so much, but it was take it or leave it. I could never say no,” said Mike.

“No cruise, two kids, it was a hell of a change.”

They stayed on Prince Edward Island, buying a house in Rusticoviille, where the North Rustico Harbour meets the Hunter River. “My family strongly supported us, they helped us get our house, and a small allowance to take care of the kids, so that we wouldn’t just be scraping by, so they could lead a normal life.”

The Levy household turned on the lights.

“The kids were a stabilizing factor in our lives, too, even though they cost me years of idyllic luxury.”

Not only had they lost the life of Riley, now they had to support their newfound children. Their fledgling catering company was growing, but it wasn’t enough. “We needed a more solid income,” said Mike. When they found the vacant Yellow House, Jennifer Levy was dead set on getting it. “Ten years from now people are going to look back, how did you get so lucky and find a nice spot like this,” she said.

They still needed funding to bring it to life. They got it when they put the problem on the doorstep of Anne Kirk, the mayor of North Rustico. “She was so pissed, so incensed,” said Mike. “I’ve got three or four businesses like yourself and nobody’s helping them,” she said. “Come back in few days.”

The mayor went to Charlottetown, the capital of the province. “She lambasted everybody about helping small businesses in rural areas,” said Mike. “Sure enough, we got our funding.” They got some from the non-profit Futurepreneur, a loan from the Bank of Canada, and kicked in the balance themselves. They opened in July 2016.

The Yellow House is not a halfway house on the way to a sandwich.

“We had Lester the Lobster Roll for lunch,” said a man with his hands full of a lobster roll. “A wonderful taste of lemon zest on a fresh and flaky roll, yummy.”

“The best ever cod burger with homemade tartar sauce,” said a woman eating a cod burger.

It’s not duck soup, either.

“The service is limited, the menu is limited, but we would go back in a heartbeat,” said a man finishing a bowl of chowder. “The food is outstanding.”

The first year their menu was take-out only. “We didn’t have any indoor seating or a public access washroom,” said Mike. They fried with a small portable unit and lived without a commercial fume hood. Mike and Jennifer did all the work. Mike was the boss and Jennifer was the decision-maker. “We cooked all the food from scratch. It was exhausting.”

The second year they renovated their washroom, added indoor and outdoor seating, and added staff. “Jen and I still do a good chunk of the cooking, but we hired a young guy, Jake, who has the right temperament to work in a hot stressful environment with lots of people yelling around you. He’s ambidextrous, too. When he’s chopping vegetables and his hand gets tired, he flips his knife into the other hand.”

Their adopted family helps out, likewise. “Maddie does a great job maintaining the garden and cleaning up after us.”

They fill their larder locally as much as possible. “We’ve got an intense island focus,” said Mike. They procure garlic from nearby Eureka Garlic. It has a deep earthy sweet flavor. Their gouda cheese comes from nearby Glasgow Glen Farm. Their cured meats come from nearby Mt. Stewart. “They smoke them like they would have a hundred years ago.”

Moving into their third year, the Levy’s continue to cater, working out of the Yellow House, servicing weddings, meet-and-greets, and Buddhist retreats.

Even though fewer than a few hundred natives of the province identify themselves as Buddhists, there are two large religious communities on the southeastern end of Prince Edward Island. The Great Enlightenment Buddhist Institute Society is for monks and the Great Wisdom Buddhist Institute is for nuns. Monks and nuns typically study for fourteen years.

“They were having a retreat and Molly Chang, the coordinator, reached out to us. We had no idea about Buddhists. When I asked her how many people would be there, she said, oh, maybe five hundred.”

There was a pause. Mike Levy tried to downplay the numbers. “Oh, we do those all the time, no problem.”

”It’s got to be vegan.”

“Sure, no problem,” repeated Mike.

The problem was how to plan prepare lick into shape that much food in the limited space of the Yellow House, transport it an hour-and-a half away, keeping the hot food hot and the chilled food chilled, get it ready to be served on time, and then serve it. “There was a lot of fear and anxiety,” said Mike. “But they were great. When you watch TV and see the super wise calm thing Buddhists do, the first nun we met did that, and it all went well.”

At the end of the event the organizers showed their gratitude to the vendors and suppliers on hand by asking them to step up on stage and take a bow. “We had taken Jacob, our eleven-year-old, with us, and after the applause, leaving the auditorium, I looked around, where’s Jacob? I looked back to the stage. There he was center stage, alone, bowing to all the Chinese people, thinking he might be the next Buddha.”

He wasn’t the next Buddha, just that day’s Buddha.

“The nuns thought he was cute as anything.”

Buddhists take as gospel that we existed before we were born and we will have another life after we die. They believe the cycle of life and death continues endlessly, or at least until one achieves enlightenment, or liberation, losing the attachment to existence in the first place.

In the meantime, no matter how many times you’re born again, they believe in being mindful of what you say and do, mindful in your livelihood, and having care and concern in your heart for others so you can, in the end, understand yourself.

Once Jacob was coaxed off stage, however, it was back to work, loading up for the road back to North Rustico.

If kitchens are the heart of all houses, the Yellow House is all heart.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”