By Ed Staskus

There were five of us on the big elevator going up to the 4th floor of the Global Center. One of us asked the others if we were all on the way to jury duty. All of us said yes, or something along those lines. “This is a pain in the ass,” one young man grumbled.

“Better to be on this side of things than the other side,” the man next to him said.

“You got that right, brother,” another man said.

The Global Center is at the corner of Ontario St. and St. Clair Ave. It is across the street from the Justice Center. It is part of the Medical Mart and Convention Center that made history in 2011. Six buildings were demolished to make way for the development. Half a million tons of debris were removed, and more than 12,000 tons of new steel was used to create the infrastructure of the new complex. It was the most steel used on any one project in Cleveland’s history.

When we got off the elevator I immediately regretted being on time. The line snaked from the elevators backwards then forwards to the sign-in tables. It looked like everybody was in line all at once. I took my place and shuffled forward like everybody else. If I need to come back tomorrow, I thought, I’m showing up late. The next day, when I did arrive late, there was hardly anybody in line.

The Global Center is mostly about conventions and industry conferences. It was the media center for the 2016 Republican National Convention, held in downtown Cleveland, when the far-right spun fantasies and the fantastic happened. The Grand Old Party put a bunko artist at the top of its ticket. The 4th floor is where those called for jury duty report every Monday morning every week of every month. The pool of jurors is usually between 300 and 400 people.

Before I went through the full-body scanner, I told one of the policemen, “I’m breaking in an after-market hip, so I’m going to set off your fire alarm.” He said all right and told me to go ahead. When I did, nothing happened, except the light blinked green for GO. The high-tech scanners are supposed to detect a wide range of metallic threats in a matter of seconds. “Essentially, the machine sends waves toward a passenger’s insides,” said Shawna Redden, a researcher who studies the devices. “The waves go through clothing and reflect whatever might be concealed, and bounce back a signal, which is interpreted by the machine.”

“Do you want me to try again?” I asked.

“No, go ahead,” the policeman said, barely paying any attention to me.

Six feet apart and masks were back in effect, even though there was no official ruling in the city, where hardly anybody was paying attention to the pandemic anymore. Only the odd man and woman wore a mask in the lobby or anywhere else. All the hard-backed chairs in the big room were in rows a social distance apart and everybody wore a mask. You can’t fight City Hall. Almost everybody kept their heads down looking at their cell phones. Some people read books. A few went to sleep on the sofas lining the walls.

When the jury pool bailiff stepped to the front of the room everybody perked up. The boss lady looked casual but was anything but, even though she sprinkled in some stale jokes. She wore a short-sleeved blouse, and her forearms were tattooed. The first thing she did was thank us for coming.

She explained since we were on the voting rolls we had been randomly selected. She thanked us for opting into our civic duty. She showed a video about the history of juries and what jury duty amounts to. A judge from Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court showed up and thanked us some more. She was wearing a dark skirt. I didn’t know judges could be so friendly and good-looking. When she was done everybody went back to their cell phones and books. The sleepy heads went back to their napping.

The bailiff said she would be calling groups of 8 for civil cases and groups of 20-and-more for criminal cases. I didn’t mind serving on either kind of jury but was hoping I wouldn’t be called to serve on a criminal case. I didn’t want to be on the jury that was going to convict Tamara McLoyd for shooting and killing Shane Bartek, a Cleveland policeman.

What would be the point? She seemed to be as guilty as Machine Gun Kelly. Somebody matching her description had been caught on surveillance video pulling the trigger. Her DNA was on the .357 Magnum. She confessed to the crime after being arrested. Why she pled not guilty and was demanding a jury trial was beyond me.

I brought my Apple tablet with me and read “Empire of the Scalpel” on it all morning. It was about the history and advancement of surgery. No matter their newfound skills of restoring life and limb, there was no bringing Shane Bartek back to life. He was gone to stay. Several groups of jurors trooped out when their names were called. When lunch was announced, I went for a walk on Lakeside Ave.

The criminal complaint against Tamara McLoyd said she walked up to the off-duty Shane Bartek on Cleveland’s west side on New Year’s Eve and robbed him at gunpoint. He was outside his apartment on his way to a Cleveland Cavs game. When he tried to take her gun away, she shot him twice during the struggle. After the shooting, she stole the policeman’s civilian car and fled. Shane Bartek was taken to Fairview Hospital and pronounced dead. He was 23 years old. She was 18 years old.

Tamara McLoyd gave the stolen car to a no-good companion of hers who was hunted down later that night by a swarm of suburban police. After a high-speed chase he lost control of the car and slammed into a fence. He didn’t bother saying he was innocent. The police didn’t bother being polite. They tracked the shooter by following videos she was posting on Instagram. She was nothing if not clueless about crime and punishment. She was run to ground, doing her best to curse her way out of capture, and was hauled away to a jail cell. Her handgun was found hidden in the back seat of the not so joyful joy ride.

She was Public Enemy No. 1 for a day. The next day she went back to being just an enemy to herself. She never interrupted that side of her whenever it was making a mistake.

The young woman had been on a crime spree most of the year. Two months earlier, five days after she was sentenced to probation in Lorain County on firearms and robbery charges, she and two accomplices robbed a man in Lakewood, robbed a woman in Cleveland Heights, and robbed Happy’s Pizza in Cleveland. They had worked up an appetite robbing people.

City Hall and the Cuyahoga County Court House are both on Lakeside Ave. I took self-guided tours during lunchtime and walked around Mall C. I looked down at the Cleveland Browns gridiron and the Science Center across the railroad tracks on the other side of Route 2. There are small parks beside both City Hall and the Court House. I checked out Claes Oldenburg’s rubber stamp sculpture in Willard Park. I checked out John T. Corrigan’s statue in Fort Huntington Park. The over-sized stamp sculpture is whimsical. The life-sized Corrigan statue is stone-faced.

Tamara McLoyd made her first court appearance on murder charges two days after New Year’s Day. “I didn’t know he was a cop,” she explained, even though nobody was asking for explanations. The cops are like the armed forces, who don’t leave their wounded or dead behind. Killing a policeman is a one-way ticket to the Big House, if not Old Sparky. A city prosecutor read into the record her admission to shooting Shane Bartek. The judge set bail at $5 million dollars and told her to find a lawyer. She hadn’t stolen enough money to make bail. She stayed locked up in the Justice Center the next seven months.

While there she talked to her friends and mother by jailhouse phone, telling them exactly what happened, and saying she expected to be famous for shooting a policeman. Her lawyers tried to suppress her original confession, but after hearing recordings of her phone calls, nixed the idea. “After consulting with our client, she has authorized and instructed us to withdraw the motion to suppress,” her lawyers said at a hearing.

John T. Corrigan was Cleveland born and bred, graduating from a local high school and university and law school. He served in the Army during World War Two, losing an eye during the Battle of the Bulge. He was elected Cuyahoga County’s prosecutor in 1956 and re-elected repeatedly, serving for thirty-five years. “It is a large office with more than 300 employees. It’s the second largest public law firm in the state of Ohio,” said Geoffey Means, a former federal prosecutor. John T. was a stern man when it came to law and order. He sent his former law partner to jail. Hoodlums knew there wouldn’t be any sympathy coming their way from the one-eyed legal eagle.

Nothing had changed since his retirement. When murder was the charge, the office was no-nonsense going forward. When the murder of a policeman was the charge, the office was bound and determined to get it done.

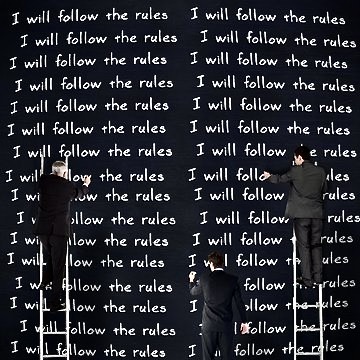

Tamara McLoyd was bound and determined to say it was an accident. “This shit wasn’t no aggravated,” she told her mother after she was charged with aggravated murder. “This shit was an accident.” Later in the month she told a friend, “We was tussling, he reached for the gun, he fell, and then pow.” She made it sound like a Bugs Bunny cartoon.

When Monday came to an end at 3 o’clock and I went home, well more than a hundred of us had been picked for actual jury duty. The rest of us came back on Tuesday. More of us were picked, lunchtime was again announced, and I went for another walk. We filtered back at 1 o’clock. I dove back into my sawbones book. A few more of us were picked for a civil trial. Just after 2 o’clock the bailiff cleared her throat.

“The last judge has just sent word that his trial has been postponed until next week,” she said. “Thank you for coming and you are free to go.”

We all cheered, collected our certificates of appreciation, and marched away to the elevators. I walked to the lot on W. 3rd St. where I had left my car. It was a cloudless day. There weren’t many people on the sidewalks. The tables and chairs of downtown’s Al Fresco dining were empty. Everybody had gone back to work after eating.

Al Fresco comes from the Italian and loosely means “in the cool air.” Unlike everybody else, Italians don’t use the term for eating outside. In Italy it means “spending time in the cooler.” When they say cooler, they mean jail.

Tamara McLoyd was found guilty of theft, grand theft, aggravated robbery, felonious assault, murder, and aggravated murder. It didn’t take the jury long. The courtroom was packed with Cleveland police officers and Bartek’s family. Some of the dead man’s relatives broke into tears. Tamara McLoyd turned 19 during the trial. She was a cold fish, standing unblinking when the verdict was read.

“What would you think after being found guilty of aggravated murder?” her lawyer Jaye Schlachet offered up, even though she didn’t seem to be thinking about anything special. Shane Bartek was probably the last thing on her mind.

“The tragedy is that this individual who committed this crime was on a spree of violence through our community,” Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Michael O’Malley said. “We see it every day in our county. She had opportunities to get on track. At every crossroad she could have turned her life around. She declined that opportunity. She was a terrorist on our streets, and for our community’s sake she is going to face the music for all the crimes she committed over those several months.”

A sheriff’s deputy put the convicted killer in handcuffs. She was led away. She was facing a life sentence. The judge would decide at her sentencing the following month whether there was going to be the possibility of parole after 25 or 30 years, or whether it was going to be life without parole.

“We are quite confident that the only thing she will see for the rest of her life are bars,” police union chief Jeff Follmer said.

Tamara McLoyd tried to explain away the shooting of Shane Bartek. I was glad I wasn’t there to hear it. After a while it’s sickening having to listen to lies. Murder is inherently wrong. She thought she was just offing somebody who was getting in her way, like brushing away a bug. She didn’t realize she was committing suicide as well as murder. She was 1-2-3 down for the count. She was going to Marysville Prison where nobody cared whether jailbirds lived or died, where she could kill time day-in and day-out.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

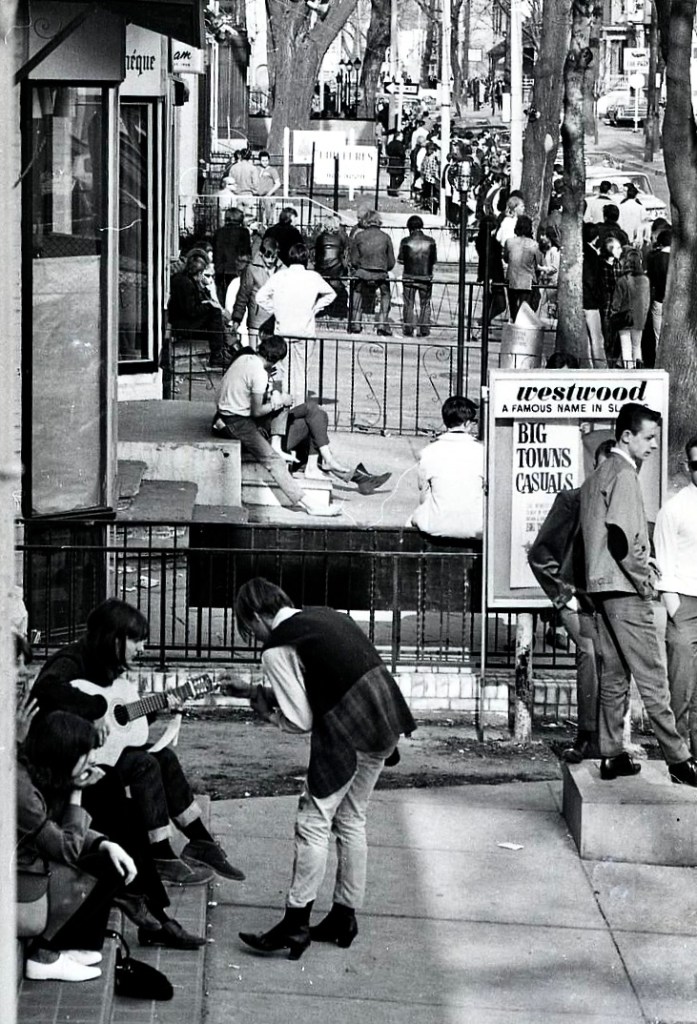

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“Captures the vibe of mid-century NYC, from stickball in the streets to the Mob on the make.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn. New York City, 1956. Jackson Pollack opens a can of worms. President Eisenhower on his way to the opening game of the World Series where a hit man waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication