By Ed Staskus

“Hey, what the hell do you think you’re doing?” Juozas Bankaitis barked coming back to his delivery truck. He had just dropped off three orders of fried chicken to a law office on the corner of 3rd St. and Yesler Way on Pioneer Square. Yesler Way was named after Henry Yesler, the founder of Seattle. A Negro man was tearing the spare tire cover off the back of his truck.

“Who the hell do you think you are calling us coons?” the man yelled back.

What is he griping about? Juozas wondered. Everybody loves coon chicken.

Juozas was new to Seattle, Washington. He had come from Cleveland, Ohio. He had emigrated to the United States from Lithuania a year after the Great Depression parked itself for the long haul. None of the work he found in Cleveland ever lasted and he decided to take his chances out west. When he got to Seattle he liked what he saw. It reminded him of his home on the Baltic Sea. He changed his name to Joe Baker. He worked for the Coon Chicken Inn making deliveries and filling in whenever the kitchen needed him. He didn’t belong to the Church of Fried Chicken, but he was good at seasoning them and making sure the cooking oil temperature never dropped below 325 degrees.

“Give that back to me,” Joe said.

“Come and get it,” the man said. His name was Joseph Stanton. He worked for the Northwest Enterprise, a local Negro newspaper. The newspaper had been founded in 1920 by William Henry Wilson. By the time Joe Baker arrived in town William Henry Wilson was thought to be the most successful Negro in Seattle.

Joe Baker and Joe Stanton each got their hands on the spare tire cover and started tugging. Before long the canvas cover tore in half. A policeman on foot patrol heard the commotion and broke up the tug of war. He arrested Joe Stanton. The Negro was booked for vandalizing an automobile. The next day in court the judge asked to see both parts of the spare tire cover. When a court attendant brought them out, the judge put the parts together and chuckled. It had Coon Chicken Inn printed on it in bold letters. Darkies could be sensitive.

There was a color picture in the middle of the spare tire cover. It was the head of a grinning bald black man with enormous lips, a winking eye, and wearing a cockeyed porter’s cap. The same bald black man’s head formed the restaurant’s 12-foot high front entryway. The door was through his grinning mouth. The logo was on every menu, dish, and piece of silverware.

“Well, I’ll just fine you three dollars and you go on home,” the judge said settling the matter by banging his gavel. Joe Stanton’s newspaper paid the fine. They padded his paycheck with a bonus the following week.

The first Coon Chicken Inn came to life in 1925 in Salt Lake City. The eatery took off the day its doors opened. Two years later the deep-fat grease-soaked place caught fire and was reduced to ashes. Fifty carpenters worked day and night for ten days building a newer bigger restaurant. An overflow crowd showed up on the eleventh day. Everybody got free dessert when they ordered the Coon Chicken Special.

The Seattle restaurant opened in 1929 on Bothell Highway, not far from Henry the Watermelon King, who sold king-sized watermelons. Just like in Salt Lake City, it was an instant success. “Anyone who has lived below the Mason-Dixon line knows that ‘coon chicken’ is the way the fowl is cooked by the old-fashioned southern mammy,” the Seattle Times reported, heedless that there were no old-fashioned southern mammy’s in the kitchen. The following year another one of the restaurants opened in Portland, Oregon. A cabaret, dance floor, and orchestra were soon added to the Salt Lake City and Seattle locations. The dance floor was where Joe Baker met Helen, who became his wife.

“I’ve always said, never put a sword in the hands of a man who can’t dance,” Helen said. “But, oh boy, you can dance.”

“I always say, if you can dance, you’ve got a chance,” Joe said. “Never mind that chicken, let’s shake a leg.”

The fried chicken restaurants were owned and operated by Maxon Graham and his wife Adelaide. Maxon had been barely 16 years old in 1913 when he answered an ad for the Metz Automobile Company. They were looking for car dealers. Maxon wrangled financing from a local bank and got distributorship rights for Utah, Idaho, and Nevada. When he did, he became the youngest car dealer in the United States. Twenty years later Maxon and Adelaine were looking for a new opportunity. They settled on fried chicken.

Most of the waiters, waitresses, and busboys at the Coon Chicken Inn were Negroes. “Their service to whites is preordained by God,” was the feeling of the day. Everybody knew, though, that they were thieving chicken-lovers. Everybody had seen their rascality in the movie “Rastus and the Chicken.” The birds were kept under strict supervision. The cooks were a mixed bag. The rest of the staff was white, especially the cashiers, bartenders, and everybody front-of-house. There were no Chinamen.

A Nevada periodical published an interview in 1972 with the grandfather of a waitress who worked at the last of the restaurants in Salt Lake City, which closed in 1957. “I was ridin’ out one day and comes across the Coon Chicken Inn. Seems like that ol’ coon head just sort of winked at me like it always done, and I’ll be dad blamed if I didn’t just wink right on back. I reckon de past ain’t all full of meanness. You got to laugh at some parts.”

Seattle’s Coon Chicken Inn often hosted meetings of clubs and civic organizations. The Democratic Club met there. Weddings, anniversaries, and birthday parties were celebrated there. There were always an array of drinks at the catered meetings and celebrations, but the food was without fail fried chicken. In 1942, long after Joe Baker had left Seattle, Coon Chicken Inn was listed in ‘Best Places to Eat,’ the nationwide guidebook of auto clubs.

Joe was filling in one busy Saturday night frying chicken one after the other when one of his friends in the kitchen pulled him aside. His name was Ernie. “You hear what the Chinamen are up to?” he asked.

“No, I haven’t heard anything.”

“They are planning on applying for work here at half our pay. It won’t be long before none of us has got no job anymore. Why don’t you join us tomorrow? We’re having a rally about what to do.”

“OK, I will,” Joe said.

The rally the next day was in a cleared field on the outskirts of Seattle. It was Sunday night. There were a thousand more men and women there than worked at the Coon Chicken Inn. Most of them were dressed in white robes. They were the rank-and-file. A few of them were dressed in green robes. They were the Grand Dragons. A dozen of them wore black robes. They were the Knighthawks, a kind of bouncer. Some of those in white had emblazoned their robes with stripes and emblems.

Almost all of them were wearing a conical shaped hat. They were dunce hats with a mask flap. Round eye holes had been cut out of the front of the mask. The eye holes were stitched to prevent fraying. There was a red tassel attached to the pointy top of the hat.

“Is this the Ku Klux Klan?” Joe asked Ernie.

“Yeah, that’s who we are,” Ernie said handing him a robe. “I couldn’t find a hood for you, but that’s all right. You’ll make do.”

Joe knew hardly anything about the Ku Klux Klan except that they hated Negroes so much they burned down their houses in the night and lynched the survivors. What he didn’t know was they hated Chinamen almost as much as Negroes. He found out later they hated Jews and Catholics as well. When he found out they hated immigrants he was offended, but by then he was no longer living in Seattle.

“I thought the Ku Klux Klan was against Negroes.”

“Chinamen are the same as niggers, lazy and shiftless.”

Joe was puzzled. It didn’t make sense. If they were lazy and shiftless, why were they trying to take everybody’s jobs? He was also puzzled that the Ku Klux Klan was in the Pacific Northwest in the first place. He thought they lived and died in Dixie.

“No, it ain’t just there. We’ve been here since right after the Civil War, the same as back home. Hell, we were here before there even was a Klan.” Before the Civil War a group calling itself the Knights of the Golden Circle promoted the cause of the Confederacy. During the war they were a Fifth Column. They meant to spread slavery and take California, Oregon, and Washington out of the Union. They planned to form a Pacific Republic allied to Dixie.

In 1868 in the Livermore Valley outside of San Francisco a circular was in wide circulation. “Action! Action! Action!” it said. “Fellow members of the KKK the days of oppression and tyranny is past, retribution and vengeance is at hand.” The circular threatened to impale those “who seek enslavement of a free people.” Their target was the Chinese. Anti-Chinese sentiment up and down the coast eventually led to the first race-based anti-immigrant laws in the United States. “ I believe this country of ours was destined for our own white race,” Senator John Hager said.

“How are you going to keep the Chinese from taking our jobs?” Joe asked.

“Stick around, you’ll see,” Ernie said. “We got the manpower to get it done.”

In the summer of 1923 200,000 Klansmen gathered in Indiana for a mass rally. There were more Klansmen in Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana than there were south of the Mason Dixon line. That same year 50,000 of them rallied at Wilson’s Station in Oregon. “Over a green sloping hill on which stand four huge crosses an endless line of white-robed Klansmen move in single file and closed ranks,” is how the magazine Watcher on the Tower described it. “They form a square covering the space of five acres standing shoulder to shoulder. Suddenly a figure appears on the brow of the hill riding a horse. A voice heralding the stars passes the word ‘Every Klansmen will salute the Imperial Cyclops.’” Two years later almost 40,000 Klansmen paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D. C. in broad daylight in full regalia.

The rally started when the sun was down and the moon was up. Ernie elbowed his way to the front, Joe following in his wake. There was a 21-gun salute. A cohort of Klansmen paraded in military formation with red, white, and blue torches. A fireworks display exploded into three gigantic K’s and parachuted hundreds of small American flags. The first speaker declared that “our progress is the phenomena of the age. It is the best, biggest, and strongest movement in American life.” A troupe of actors reenacted scenes from D. W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation.” A local minister gave a sermon, calling for “an army of Christ to demand the continued supremacy of the white race as the only safeguard of the institutions and civilization of our country.”

The imperial Cyclops was the last to speak. “We believe that the mission of America under Almighty God is to perpetuate the kind of civilization which our forefathers created. It should remain the same kind that was brought forth upon this continent. We believe races of men are as distinct as breeds of animals and that any mixture between races is evil. Our stock has proven its value and should not be mongrelized. We hold firmly that America belongs to Americans. Within a few years the land of our fathers will either be saved or lost. All who wish to see it saved must work with us.”

At the end of the rally a three story wooden cross was set on fire. Everybody watched as it slowly started to lean and toppled to the ground. The traffic jam leaving the Konklovation was long, clogging the rural roads. Sheriffs from Seattle helped direct traffic.

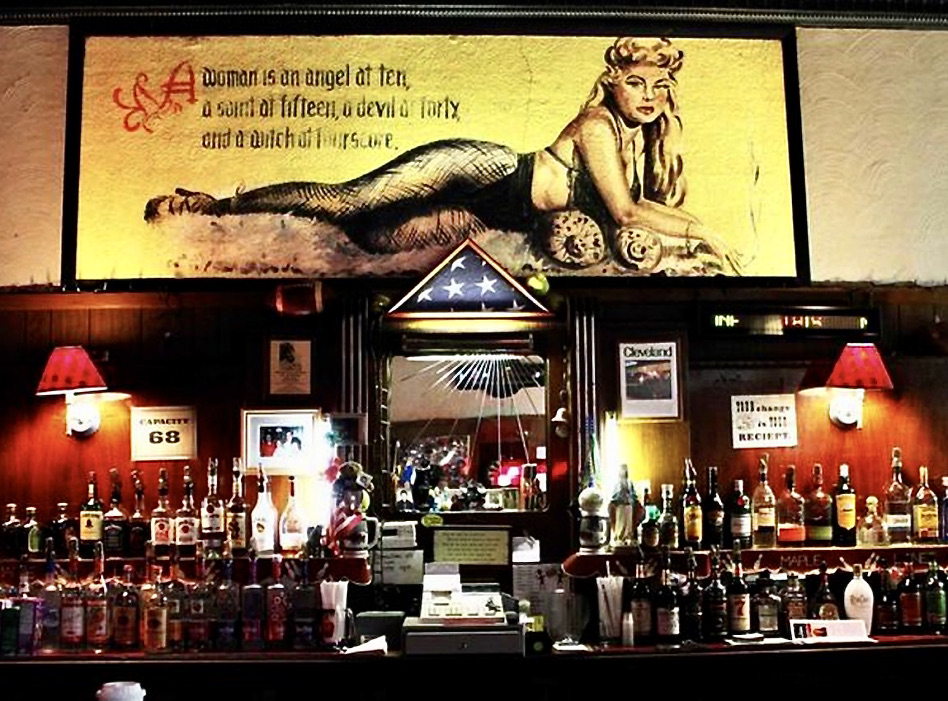

Ernie drove to the heart of the city and stopped in front of the Merchants Cafe on Pioneer Square. It was the oldest bar in town. They had never stopped serving booze, Prohibition or no Prohibition. It was built long ago by W.E. Boone, who was a direct descendant of Daniel Boone. The upstairs had once been a brothel. The whores were known as seamstresses. It was their codeword.

Joe and Ernie sat down on the last two stools at the bar and ordered mugs of beer. ‘Here’s to You!’ was emblazoned on the stoneware mugs. The beer was a top-fermented local ale. It was cold and refreshing.

“I watched the parades, listened to all the speeches, and I saw the cross burn, but I still don’t understand how the Ku Klux Klan is going to save our jobs,” Joe said. “Nobody said a word about it.”

“All the words were about saving our jobs,” Ernie said. “You got to listen between the lines. First, we’re going to jump some of the Chinamen and teach them a lesson. If they don’t learn their lesson then we’ll burn some of their shacks down. If they still won’t listen to reason, we’ll string one or two of them up. That should take care of it. They’ll be out of Seattle soon enough.”

Later that night, snug in bed, Joe and Helen talked about what was going on and what was in the works. Neither of them liked it. Helen’s grandparents had come from Poland, which like Joe’s Lithuania, had been an unwilling unhappy colony of Russia for a long time. Both countries had gotten their freedom back only after World War One, after a hundred and fifty-some years of tyranny.

“My father told me all about the Russians,” Joe said. “They treated us like the Ku Klux Klan treats Negroes and Chinamen.”

The Lithuanian legal code, originating in the 16th century, was quashed. Russian apparatchiks occupied all the posts of power. Arrests and detention were at their discretion, no matter if a crime had been committed, or not. Russian was the only language allowed to be spoken in public. Teaching the Lithuanian language in schools was forbidden. No arguments were brooked. Books and magazines could be printed only in the Cyrillic alphabet. Latin script was forbidden. Books in Lithuanian in Latin script, printed in East Prussia, had to be smuggled into the country. When they were caught, some of the book carriers were shot on the spot. The rest were exiled to Siberia. The term of exile was 99 years to life.

“What should we do?” Helen asked.

“I think we should leave this place,” Joe said.

Joe and Helen packed two suitcases and a sea bag early the following Saturday morning. Joe had cashed his weekly paycheck the day before and consolidated their savings, which he entrusted to a money belt. He had warned the head man of the Chinamen in Seattle about what the Ku Klux Klan was planning. He didn’t bother warning the police. Enough of them were Klansmen to make telling them unwise. Joe and Helen took a ferry to Vancouver Island, landing in the town of Victoria after a three hour ride. They took a bus to Port Hardy on the northeast tip of the island, just inside the Arctic Circle.

At first they both worked at the Bones Bay Cannery, but within two years had saved enough to open their own business. The business was a bakery. They called it Baker’s Bakery. The first employee they hired the next year, after getting their legs under them, was a Chinese immigrant willing to work for low pay.

“Why you use same name twice?” he asked looking at the sign above the front door.

“Because our bread is twice as good,” Joe said.

“You pay me more when I make it three times as good?”

“You be square with me and I’ll be square with you.”

No man is an island, but Vancouver Island suited Joe and Helen. He wrote a letter to his parents in Lithuania telling them where he was, but the letter was lost and never delivered. She got pregnant and pregnant again. Their children were born Canadians. Growing up they would have laughed their heads off if anyone had told them about the KKK, about their variety show antics and Halloween-style hoods and robes. They would have hung their heads if anybody had told them about the KKK’s deadly serious night rides. As it was, nobody ever told them, at least not until they came of age and had a better understanding of gods and monsters.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street at http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

Help support these stories. $25 a year (7 cents a day). Contact edwardstaskus@gmail.com with “Contribution” in the subject line. Payments processed by Stripe.

“Telling of Monsters” by Ed Staskus

“21st century folk tales for everybody, whether you believe in monsters, or not.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon:

Oliver and Emma live in northeast Ohio near Lake Erie. The day they clashed with their first monster he was six years old and she was eight years old. They fought off a troll menacing their neighborhood. From that day on they became the Monster Hunters.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication