By Ed Staskus

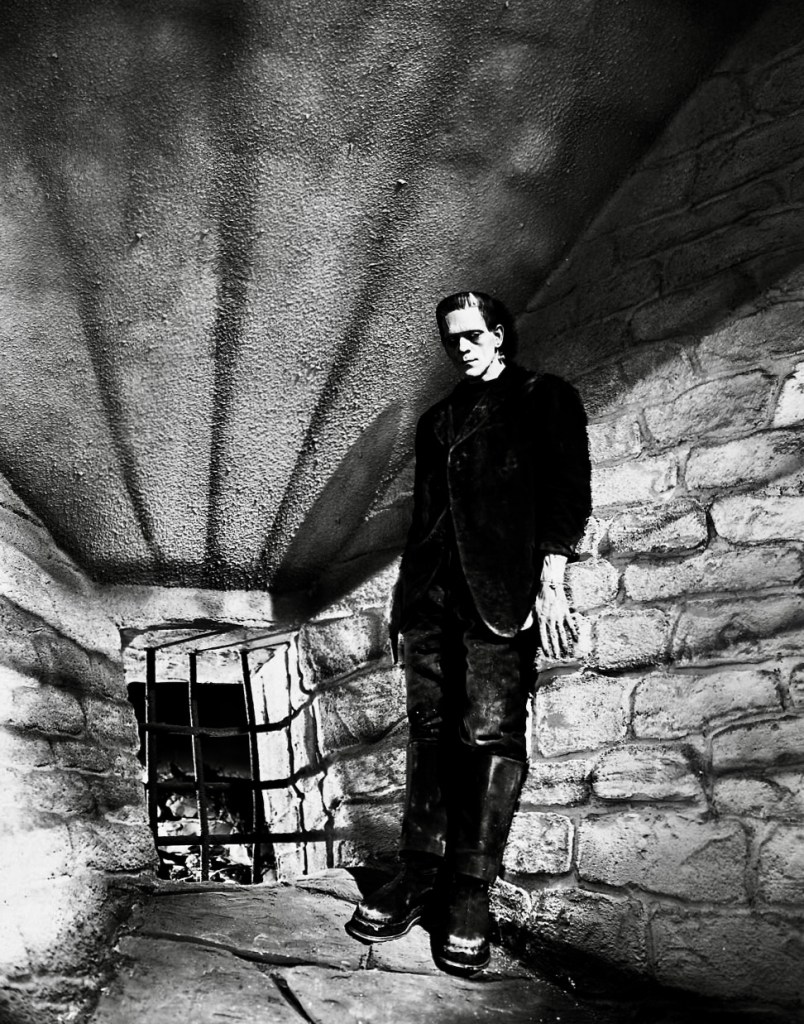

The day Frankenstein walked into Barron Cannon’s yoga studio in Lakewood, Ohio, Barron could tell he wasn’t a happy monster. He walked as though he had never gotten over the rigor mortis of all his lives and deaths before being resurrected by Victor Frankenstein. He was dirty as all get out and wet. His boots were caked with muck and mire. He needed a haircut and a shave. He looked like he could use ten or twelve square meals all at once.

“You look like hell,” Barron said.

“I feel like hell,” Frankenstein said.

“I thought you were dead and gone, and only alive in the movies,” Barron said. “The story is you killed yourself up on the North Pole after Victor died. That would have been a couple hundred years ago.”

After being chased and pelted with rocks, flaming stave torches shoved into his face, shot at and thrown into chains, Frankenstein had sworn revenge against all mankind. They hated him so he would hate them. He had hated himself, as well, for a long time.

“I was going to end it all when I floated off on an ice floe, but I froze solid, and it wasn’t until twenty summers ago that I defrosted.”

A heartwarming result of global warming, Barron thought to himself.

“After defrosting I lost track of time,” the creature said. “It’s either all day or all night almost all the time. I built an igloo and learned to hunt seals. I caught and beat their brains out with my bare hands. I meant to go back to Geneva. But after living on the ice safe and sound, I changed my mind. There wasn’t anybody anywhere trying to kill me, which was a blessing. But then I got lonely.”

“How did you get here?” Barron asked.

“I walked.”

“It’s got to be three, four thousand miles from the pole to here. How long did it take you?”

“I meant to go back to Germany, but I took a wrong turn at the top of the world. Canada looked like Russia until I got to Toronto. By then I didn’t want to turn around. I had been at it for five months. I kept walking until I reached Perry, on Lake Erie. I met a boy and girl there. They were riding pedal go-karts on the bluffs. The girl said her brother was the Unofficial Monster Hunter of Lake County. It was hard to believe. He’s nothing more than a tadpole. When I asked him whether he thought I was a monster, he said I looked monstrous, but was sure I wasn’t a monster.”

Frankenstein had seen his own reflection in water. He was aware of what he looked like. He didn’t like it any more than passersby did, throwing him wary nervous glances and scuttling away.

“Was his name Oliver?”

“Yes.”

“You didn’t throw him and his sister down a well, or anything like that, did you?”

“No, and I’m glad I didn’t. They helped me. They gave me some of their homemade granola bars.”

“Don’t underestimate the boy. He’s taken on banshees and trolls, the 19 virus, Bigfoot, Goo Goo Godzilla, and the King of the Monsters himself. I don’t know how he does it, but he’s no ordinary child to mess with.”

“He told me to come here and talk to you, that you were a yoga teacher and could unstraighten me. I’m stiff as a board all the time.”

“I can see that,” Barron said.

“I want to be able to touch my toes. I want to be a better man.”

“I can help you with that,” Barron said. “Except the better person part. That’s up to you.”

“I was benevolent and good once,” Frankenstein said. “Misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.”

“I’ll do my best.”

For once, Frankenstein had the feeling he had found a true friend.

After Barron got back from the Goodwill store with XXL shorts and muscle t’s, pants and shirts, and threw away Frankenstein’s clothes, which hadn’t been washed in centuries, they got started on the yoga mat. Barron told him to get barefoot. When he did the smell was bad. Barron turned on the studio’s fans and opened both the front and back doors. He took the creature’s boots outside and tossed them in the dumpster. The dumpster burped and spit the boots back out. They landed in the parking lot with a clomp. Barron doused them with gasoline and burned them.

“We’ll start with the twelve must-know poses for beginners,” Barron said.

Frankenstein had no problem doing the mountain and plank poses, but that was the beginning and end of what he could do. He couldn’t do down dog or a lunge to save his life. Triangle, dancer’s pose, and half pigeon pose might as well have been rocket science. When he tried seated forward fold, he folded forward an inch or two and farted.

“More roughage in those granola bars than you’re used to?”

“I lived on seal blubber for a long time,” Frankenstein said.

He could do some of the hardest poses easily, like headstand. He balanced on his flat head like nobody’s business. He chanted like a champ, his baritone voice deep and rich.. He did dead man’s pose like he was born to it.

When the lesson was over, however, he wasn’t able to get up out of laydown. His muscles were in knots. Barron pulled out his Theragun and went to work. It took all the percussion device’s battery power to get Frankenstein on his feet and into the storeroom, where Barron prepared a bedroll.

“It doesn’t look like you’re in any condition to go anywhere, but make sure you stay here. I have three classes back-to-back-to-back. I don’t want you barging through the door and causing any heart attacks.”

Frankenstein groaned and rolled over. He slept the rest of the day, that night, and part of the next day. Barron took him to the barber shop next door. Frankenstein had never gotten a haircut. His hair was halfway down his back and his beard down to his belly button. The barber gave him a taper fade crew cut and a shave. He trimmed his eyebrows and the tufts of hair growing out of his ears. He unscrewed the electrodes in the creature’s neck.

The incisions around his neck, wrists, and ankles had long since healed. Barron found a pair of size 34 sneakers and second-hand bifocals for him. Frankenstein was out of practice, but he enjoyed reading. Barron bought two dozen thrillers, biographies, histories at the Friends of the Library sale.

Monday morning dawned warmand bright. Barron and Frankenstein walked to Lakewood Park, where they could unroll their mats outdoors on the shore of Lake Erie. Barron had sewn two mats together for the big guy. Barron’s one goal was to make the creature more flexible. His unhappiness with the human race would have to wait. He wasn’t killing anybody anymore, at least. Frankenstein’s problem wasn’t a desk job and never exercising. He wasn’t rigid with chronic tension. He had been on an all-blubber diet for decades but enjoyed the plant-based diet Barron was converting him to. They started having breakfast at Cleveland Vegan.

He had never stretched in his life, which contributed to his discomfort and stiffness. His poor muscles were as short as could be. On top of everything else he was close to three hundred years old, counting his own lifetime and the lifetimes of the men he was made of. His synovial fluid was thick as mud.

Barron and Frankenstein worked on standing forward bend hour after hour day after day. At first the creature could only bend slightly, placing his hands on his thighs. He did it a thousand times. He huffed and puffed. When he was able to touch his knees, he did it two thousand times. He broke out into a sweat. One day Barron brought blocks, setting them up on the high level. Frankenstein folded and got his fingertips to the blocks. The day came when Barron flipped them to their lower level.

“Don’t be a Raggedy Ann doll, just flopping over,” Barron told him. “Do it right.”

The gold star moment finally arrived when Frankenstein folded forward without blocks. His upper back wasn’t rounded, his chest was open, his legs were straight, and his spine was long. He was engaged but relaxed. He took several steady breaths as the space between his ribs and pelvis grew.

“Great job, Frank,” Barron said with encouragement.

Frankenstein did the pose three thousand times. He was looking lean and not so mean. His skin was losing its yellow luster. He was getting a tan in the sunshine at the park. According to B.K.S. Iyengar, Uttanasana slows down the heartbeat, tones the liver spleen kidneys, and rejuvenates the spinal nerves. He explained that after practicing it “one feels calm and cool, the eyes start to glow, and the mind feels at peace.”

They walked to Mitchell’s Homemade Ice Cream in Rocky River. Barron had a scoop. Frankenstein had eight scoops. Children gathered around him asking a million questions, asking for his autograph, and asking for selfies with him in the picture. He was a ham with glowing eyes and never said no.

From standing forward bend it was on to more beginner poses, then intermediate poses. By the end of the month Frankenstein wasn’t a yogi, yet, but he was more human than he had ever been. He joined Barron’s regularly scheduled classes. He was two and three feet bigger than anybody else. Barron put him in a back corner by himself where he wouldn’t accidentally clobber anybody while doing sun salutations.

When the time came for Frankenstein to move out of Barron’s storeroom into his own apartment, Barron made him a gift of B.K.S. Iyengar’s book “Light on Yoga.”

“This is the book that will make you a better person, Frank. I’ve read it twice.”

“I’ll read it a hundred times,” Frankenstein said.

“What do you plan on doing with your life?” Barron asked.

Frankenstein thought about becoming a barber like the man who tended to him but bending over the tops of heads all day long would lead to lower back pain sooner or later. He knew full well he had arthritis. He threw that idea away. He thought about becoming a house painter. He could reach more areas compared to a shorter man. He could cut in walls and ceilings without using a ladder. That would save hours over the course of a job. The downside was having to paint low, like skirting boards. Stooping would do a number on his back. He threw that idea out the window, too.

When he finally decided what to do, he was surprised he hadn’t thought of it earlier. It was a natural. It was how he had been granted a second life. He would be become an electrician.

An electrician is a tradesman who repairs, inspects, and installs wires, fixtures, and equipment. Much of the job involves installing fans and lights into ceilings. Being tall would free him from the need to go up and down a ladder for every install. It turns the work from a two-man job into a one-very-tall-man job. Homeowners in Lakewood were always restoring and upgrading their houses. He would advertise himself as “Call Frank – He Knows the Power of Electricity and Will Save You Money.”

If he ever made a mistake, he knew he could absorb the bust-up of voltage. He had already been hit with more of the hot stuff than any mortal man and lived to tell the tale. He would look for another Bride of Frankenstein, too, a nice girl with a slam-bam bolt of lightning in her hair. They would make little Frankie’s.

Ed Staskus posts stories on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Cleveland Ohio Daybook http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”