By Ed Staskus

The mid-summer day I walked across the Rainbow Bridge the sky was getting dark and stormy. I had gotten to the border by leaving the driving to Greyhound. The driver wore a uniform and cap. It made him look like a mix of state trooper and doorman. Since the bus had no acceleration to speak of, once he got it up to speed he drove all-out all the way from Cleveland, Ohio to Niagara Falls, New York. We passed sports cars and muscle cars.

The driver’s seat was high up with a vista vision view of the highway. The transmission was a hands-on four-speed. There were four instruments visible on the panel on the other side of the steering wheel, a speedometer, air pressure gauge for the brakes, oil pressure gauge, and a water temperature gauge.

When I stepped foot on the Canadian side of the bridge it wasn’t raining, yet. The Border Patrol officer asked me where I was from, where I was going, for how long, and waved me through without any more questions. I found the bus station and bought a ticket for Toronto, where I was going. I was going to see a girl, Grazina, who I had met at a Lithuanian summer camp on Wasaga Beach a couple of years before.

It rained hard all the way there, past Hamilton and Mississauga on the Queen Elizabeth Way, until I got to the big city, where the clouds parted and the sun came out. Everything smelled clean. I picked up a map of the bus and subway system and found my way to my friend Paul’s house where I was going to stay. His family was friends with my family from back when we lived in Canada.

The Kolyciai lived in a two-story brick row house off College St. near Little Italy. I was polite to his parents and ignored his two younger sisters. I roomed with Paul, but ditched him every morning after breakfast, hopping a bus to Grazina’s house. Girls came first. It wasn’t far, 5-or-so minutes away near St. John the Baptist Church. Lithuanians bought the church in 1928 and redesigned it in the Baltic way in 1956. They tore the roof off and replaced it with a traditional Lithuanian village house roof with a sun-cross on top.

Grazina, whose name meant “beautiful” in English, met me on her front porch and took me on a guided tour of Toronto. We went by tennis shoe, streetcar, and the underground. We looked the city over from the observation deck on top of City Hall and went to the waterfront. We strolled around Nathan Philips Square. We had strong tea and swarm cones at an outdoor café. Grazina popped in and out of shops on Gerrard St. checking out MOD fashions. At the end of the day I was dog tired. I begged off a warmed-over dinner Paul’s mother offered me back at home away from home and fell into bed.

The next morning, she had a surprise for me. We weren’t going wandering, even though I felt refreshed. We were going to a funeral.

“Who died?” I asked.

“Nobody I probably know and for sure nobody you know,” she said.

She was dressed for death, all in black. I wasn’t, wearing blue jeans and a madras shirt. We stopped at a second-hand clothes store. I bought a black shirt so I wouldn’t stick out like a sore thumb.

“Why are we going to this funeral?” I asked.

“Because it’s Friday and it’s a Greek funeral,” she said as though that explained everything.

I was an old hand at funerals, having swung a thurible at many of them when I was an altar boy at St George Catholic Church. I had only ever been to Lithuanian funeral services. “Because it’s Friday and a Greek funeral” were obscure reasons to me, but I was willing to go along.

Toronto was full of immigrants. Immediately after the World War Two both war-time brides and children fathered by Canadian soldiers showed up. Post-WW2 refugee Italians, Jews, Poles, Ukrainians, Central Europeans, and Balts poured in. In 1956 after Soviet tanks rolled through Budapest, Hungarians came over. Through the 1950s and 60s the old-stock Anglo-Canadianism of Toronto was being slowly transformed.

The church, Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox, in the former Clinton Street Methodist building, was somewhere up Little Italy way. We got on a bus. When we got there a priest sporting a shaggy beard, Father Pasisios, was leading the service. He wore a funny looking hat. The church was small on the outside but big on the inside. We sat quietly in the back. When the service was over I finally asked Grazina, “Why are we here?”

“For the repast.”

“What’s that?”

“Food, usually a full meal.”

“Doesn’t your family feed you?”

“It’s not that,” she said. “I went to a Romanian funeral with a friend a few months ago, and they served food afterwards, and it was great, the kind of food I had never had before. After a while I started going to different funerals whenever I could, always on Fridays. It didn’t matter if they were Sicilian, Czechoslovakian, Macedonian, only that I could sample their national food.”

“How do you know where to go?”

“I read the death notices in the newspaper.”

I had heard of wedding crashers, but never a funeral crasher.

The repast was at a next-door community hall. Grazina was dodgy when asked, telling both sides of the family she was distantly related to the other side of the family. “Memory eternal” is what she always said next, shaking somebody’s hand. She knew the lingo. The lunch was delicious, consisting of moussaka, mesimeriano, and gyros. We had coffee and baklava for dessert. By the time we left we were well fed and ready for the rest of the day..

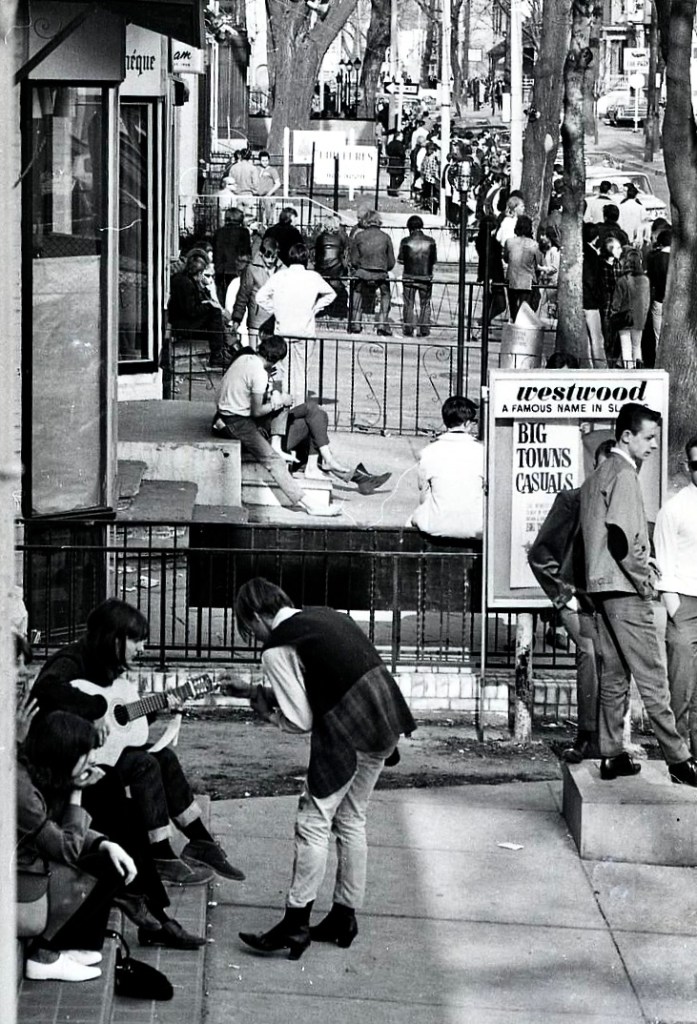

We went to Yorkville and hung around the rest of the day. It was like going to another country. There were coffee houses and music clubs all over Yonge and Bloor Streets. The neighborhood went back to the 1830s when it was a suburban retreat. Fifty years later it was annexed by the city of Toronto and until the early 1960s was quaint and quiet turf. Then it morphed into a haven of counterculture.

“An explosion of youthful literary and musical talent is appearing on small stages in smoky coffee houses, next to edgy art galleries and funky fashion boutiques offering trendy garb, blow-up chairs, black light posters and hookah pipes, all housed in shabby Victorian row houses,” the Toronto Star said.

It was fun roaming around, hopscotching, ducking in and out, even though a police paddy wagon was parked at the corner of Hazelton and Yorkville. There had been love-ins, sit-ins, and so-called “hippie brawls” in recent years. Some of the leading citizens were up in arms. The politician Syl Apps said the area was a “festering sore in the middle of the city.” There were wide-eyed teenagers and tourists, hippies and bohemians, hawkers and peddlers, and sullen-looking bikers.

A young man was slumped on the sidewalk, We stopped to take a peek at him lying dazed against a storefront. An old woman wearing a babushka and walking with a cane crept carefully past him. I couldn’t tell who was more over a barrel. We went our own way.

We weren’t able to get into the Riverboat Coffeehouse, which wasn’t really a coffeehouse, but a club with the best music in town. We peeked through the porthole windows but all we saw were shadows. The Mynah Bird featured go-go dancers in glass cases. Some of the glass cases were on the outside front of the club. We saw Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins perform back flips across the stage while doing guitar solos at Le Coq d’Or.

Starvin’ Marvin’s Burlesque Palace was somewhere upstairs, but we didn’t go there. All the clubs were small and most of the doors open to catch a breeze. We sat on curbs and heard a half-dozen bands free of charge. We stayed until midnight. By the time I got back to Paul’s house I was more than tired again and fell into bed. I caught more than forty winks.

The sky on Saturday morning was clear and bright over Lake Ontario. Grazina and I went to the Toronto Islands. We took the Sam McBride ferry and rented bikes. There were no cars or busses. We stopped at the new Centreville Amusement Park on Middle Island and rode the carousel. When we found a beach we changed, threw a towel down, and spent the remainder of the afternoon in the sun. We had bananas and threw the peels to the seagulls, who tore them apart and downed them like it was their last meal.

Grazina invited me over for dinner. She told me her mother was a bad cook, but I went anyway. She set the table while her mother brought platters of cepelinai, with bacon and sour cream on the side, serving them piping hot and covered with gravy. They were fit for a king. I told Grazina her mother was the queen of the Baltic kitchen.

The next morning was Sunday. After going to mass with Grazina and her family I caught a bus for home. At the border I waited my turn to answer the Border Patrol man’s questions. I had all the answers except one. When he asked me for I. D., I said I didn’t have any.

“How did you get into Canada?”

“I walked over the bridge.”

“Didn’t they ask you for I. D.?”

“No,” I said.

“Jesus Christ! Well, you can’t come into the United States without identification.”

I was born in Sudbury, Ontario and had returned to Canada many times since for summer camps, but had never overconcerned myself with the legalities. I left that to whoever was driving the car, who were my parents or somebody else’s parents.

I was speechless. Distress must have showed on my face. The Border Patrol man told me to call my parents and ask them to bring identification. It sounded like a good idea, except that it wasn’t. My father was out of town on business and my mother worked at a supermarket. Even if she was willing, she had never driven a car that far in her life.

“Is there any place I can stay?”

“Do you have any money?

“Just enough for a bus ticket home.”

He said Jesus Christ a few more times and finally suggested what he called a “hippie flophouse” on Clifton Hill. He gave me directions and I found it easily enough. I used the pay phone to call my mother, reversing the charges. After she calmed down, she said she would send what I needed the next morning by overnight mail. I was in for two nights of roughing it.

The flophouse was an old motel advertising “Family Rates.” It was next to a Snack Bar selling hot dogs and pizza by the slice. There were young guys and girls loitering, lounging, and smoking pot in the courtyard. One of them offered me a pillow and the floor. I accepted on the spot before he drifted down and out. It was better than sleeping in the great outdoors.

I spent the next day exploring Niagara Falls. There were pancake houses and waffle houses. There were magic museums and wax museums There were arcades and Ripley’s Odditorium. I took a walk through the botanical gardens and to the Horseshoe Falls. That summer the Horseshoe Falls were tilting water over the edge like there was no tomorrow. The American Falls, on the other hand, had been shut down by the Army Corp of Engineers to study erosion and instability. They had built a 600-foot dam across the Niagara River, which meant 60,000 gallons of water a second were being diverted over the larger Canadian waterfall. It was loud as a mosh pit and a vast mist floated up into my face.

The Niagara River drains into Lake Ontario. I lived in Cleveland a block from Lake Erie. If I threw myself into the Niagara River I would first have to avoid the falls and then swim upstream all the way to Buffalo before I could relax and float home on Lake Erie. It was an idea, but the practical side of me discarded the idea.

Many people have gone over the falls. As far as anybody knows the first person to try it was Sam Patch, better known as the Yankee Leaper, who jumped 120 feet from an outstretched ladder down to the base of the falls. He survived, but many of the daredevils who followed him didn’t. The first person to successfully take the plunge in a barrel was schoolteacher Annie Taylor in 1901. Busted flat, she thought up the stunt as a way of becoming rich and famous. The first thing she did was build a test model, stuff her housecat into it, and throw it over the side. When the cat made it unscathed, she adapted a person-sized pickle barrel and shoved off. It was her birthday. She told everybody she was 43, although she was really 63.

After she made it to safety with only bumps and bruises she became famous, but missed out on riches. Everybody said she should have sold tickets to the show, but it was Monday morning quarterbacking. She never tried it again. Two years later the professional baseball player Ed Delahanty tried it while dead drunk. The booze didn’t help. He drowned right away. About twenty people perish going over the falls every year. Most of them are suicides. The others amount to the same thing.

The last person in the 1960s to go over the falls with the intention of staying alive was Nathan Boya in a big rubber ball nicknamed the “Plunge-O-Sphere.” When it hit the rocks at the bottom it bounced and bounced. He didn’t break any bones, although he had friction burns all over him.

I got my official papers on Tuesday, dutifully displayed them at the border, and walked into the United States. I bought a bus ticket home. I sat in the back of the Greyhound and stretched my legs out. When it lumbered off, I took a look back, but it was all a blur through the smudgy window.

Grazina and I wrote letters to one another that winter until we didn’t. We slowly ran out of words and by the next year were completely out of them. She was enrolled in a Toronto university full-time by then while I was working half the year and going to Cleveland State University the other half of the year. She found a hometown boyfriend and I found an apartment on the bohemian near east side of Cleveland.

It was a few years later that Henri Rechatin, his wife Janyck, and friend Frank Lucas rode across the Niagara River near the downstream whirlpool on a motorcycle, riding the cables of the Spanish Aero Car. The friend piloted the motorcycle while Henri and Janyck balanced on attached perches. Since they didn’t have passports, when they got to the far side, they hauled the motorcycle and themselves into the aero car and rode back in comfort.

The Border Patrol was waiting for them. They were arrested for performing a dangerous act, but formal charges were never filed. They were free to go. For my part, I made sure to always have something official with my picture on it whenever I went anywhere foreign after that. I had learned my lesson in Niagara Falls. Getting stuck in limbo, no matter if it’s one of the ‘Seven Natural Wonders of North America’ or not, is captivating for only so long.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

The end of summer, New York City, 1956. Stickball in the streets and the Mob on the make. President Eisenhower on his way to Ebbets Field for the opening game of the World Series. A torpedo waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication